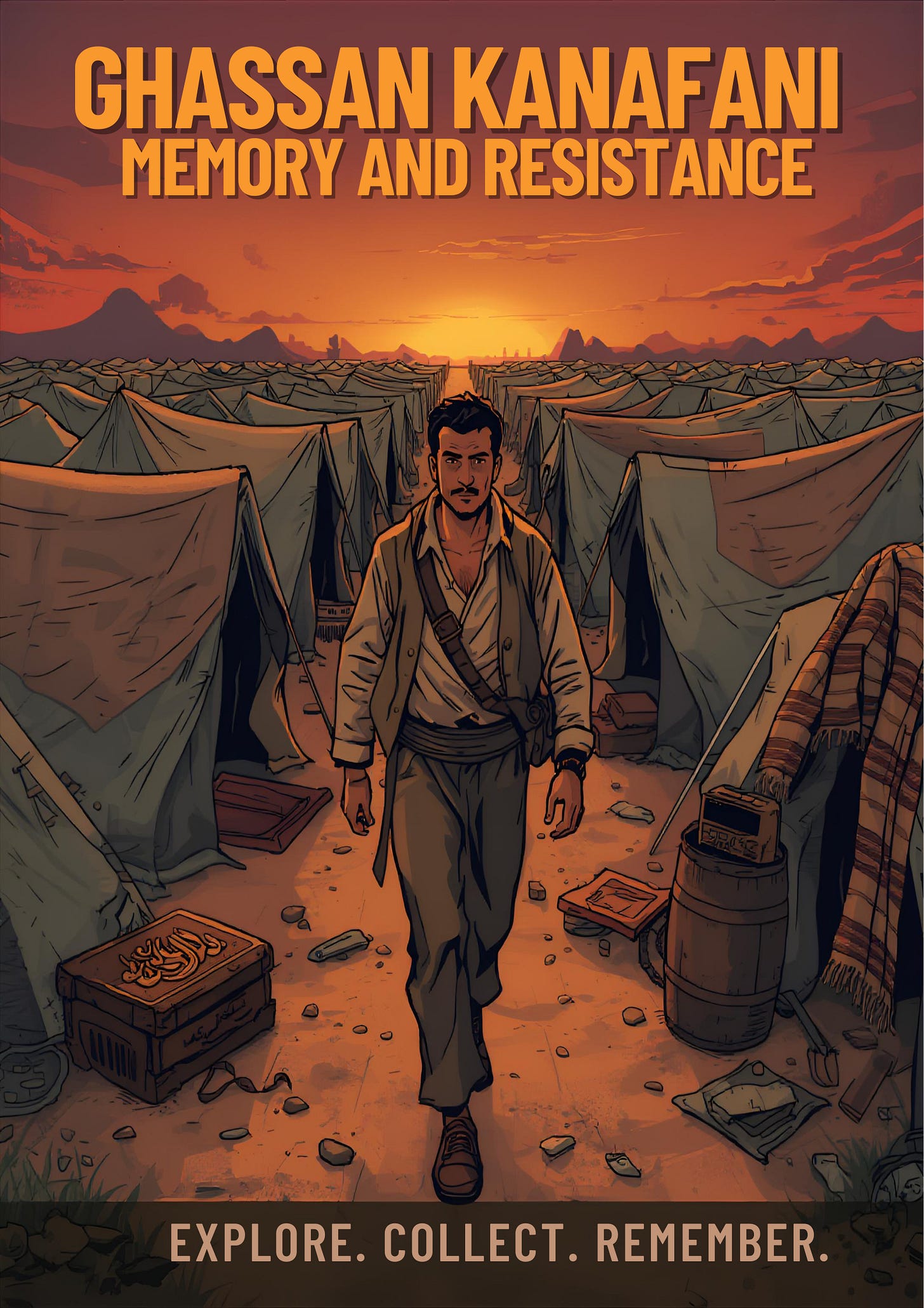

A Life Defined by Exile: The Tragic Genius Who Refused to Forget Palestine

Play & learn about Kanafani's arty refugee experience 🎮

Click here to play & learn.

Back Story

An explosion rips through Hazmieh, a leafy, well-heeled suburb of Beirut. Plumes of smoke billow from the smoldering wreck of an Austin 1100. Mangled scraps of metal lie scattered on the street, and the air is choked with ash. The blackened body of a young girl, thrown meters from the baking heap, is shrivelling in the sun. The year is 1972, Lebanon is sweltering, and a man has been assassinated. The perpetrators are the Mossad, Israel’s foreign intelligence service. Their target is Ghassan Kanafani–refugee, writer, revolutionary.

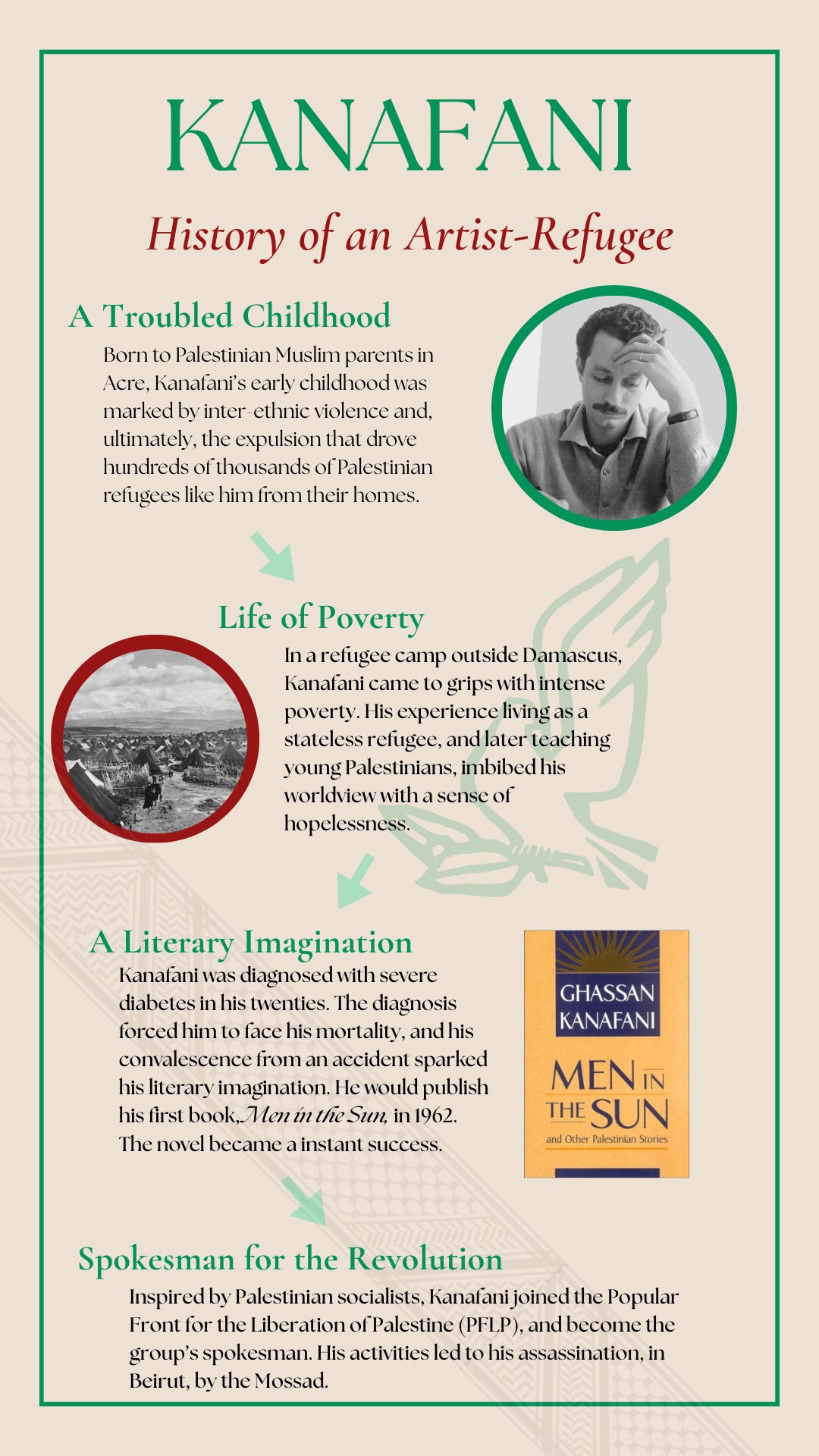

Ghassan Kanafani was born in 1936 in Acre, a coastal city in the north of Palestine that radiates Crusader history. Kanafani’s Palestine was a turbulent one; in the year of his birth, the local Arab population rose in revolt against the British, who had been governing Palestine as a League of Nations mandate. The Arabs objected to British plans, formally articulated in the 1917 Balfour Declaration, to create a national home for Jewish immigrants on their lands. The Kanafani family moved to Jaffa, south of Acre, in 1938, and the Arab revolt was crushed.

But war is never absent for long in the Holy Land. By 1948, sectarian clashes between British authorities, Jewish insurgents and Arab factions had boiled over into vicious armed conflict. The Jewish insurgents won out, established the State of Israel and scattered roughly 700,000 Palestinians to the neighbouring Arab countries–a catastrophe Palestinians know as “the Nakba.” Kanafani, then twelve years old, fled with his family to Damascus, never to see his native land again.

The experience of expulsion and exile haunts Kanafani’s literary imagination. In his first novel, Men in the Sun, he narrates three Palestinian men’s tragic quest to smuggle themselves into Kuwait, where they imagine great opportunities lying in store. The three men end up suffocating to death in an empty water tank, hidden in the truck of a smuggler. Kanafani’s work limns the grueling poverty of the Nakba generation, the listlessness of young Palestinians ripped from their homes, and the cynicism of those who exploit Palestine’s tragedy for their own ends.

But Kanafani’s literature is not just one of loss and despair; it is also one of resistance and reckoning. In his epistolary fiction “Letter from Gaza,” Kanafani imagines a young Palestinian rejecting an offer to study at a California university. “I won’t follow you to ‘the land where there is greenery, water and lovely faces’ as you wrote. No, I’ll stay here, and I won’t ever leave,” the young man tells his confidant, the expatriate Mustapha. At the end of the letter, the author entreats Mustapha to return to Gaza and rediscover the people he has left behind. To be Palestinian for Kanafani was to remain and to resist, a concept Palestinians call sumud.

Kanafani’s spirit of resistance led him into politics, where he excelled as a communicator. Mentored by George Habash, an influential Palestinian Christian politician, Kanafani joined the ranks of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a militant leftist group that formed the radical wing of the Palestine Liberation Organization. A handsome, square-jawed man, with lush black hair, a well-groomed chevron moustache and intense, globular eyes, his image became synonymous with Palestinian resistance to Israeli rule. Kanafani wrote prodigiously for Palestinian magazines, excoriated Israel’s occupation in fluent English to foreign press and dismissed the prospect of a peaceful settlement with Israeli leaders. In an interview with Australian journalist Richard Carlton, Kanafani memorably likened negotiations with Israel to a “conversation between the sword and the neck”

Kanafani’s abrasive activism garnered him the attention of Israeli officials, who denounced him as a terrorist. Kanafani did not shy away from defending acts of terror, though there is no evidence he participated in or commanded any violent action himself. Kanafani lauded the killing of 26 people in the Lod airport massacre, committed by the Japanese Red Army in concert with the PFLP, in July 1972. Just days after the killings in Lod, Mossad assassins booby-trapped his car. Then, on a fateful summer morning, Kanafani climbed into the grey Austin 1100 with his niece Lamees and started the engine, thereby setting off the bomb that killed them both. He was 36. Lamees was 17.

The Israeli press claimed that Kanafani’s death was retribution for the 1972 Lod attack, though some in the country have challenged that interpretation and suggest that he was marked for killing much earlier. In any case, Kanafani was one of the first in a spree of Israeli assassinations targeting PFLP and PLO leaders, a campaign Israeli officials stepped up following the massacre of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics the same year. Kanafani was unique, however, among targets of Israeli assassinations, who were usually commandos or military leaders. The Mossad has never accepted responsibility for Kanafani’s death, much less explained its reasons for targeting him.

Although he died young, Kanafani has enjoyed a long afterlife as a literary figure and cultural icon. Along with poet Mahmoud Darwish, he is considered to have provided Palestine’s definitive contribution to the modern Arab literary canon. Monuments to Kanafani have gone up, including in his native Acre, though that monument was ultimately removed on the instructions of right-wing Israeli politicians.

Contemporaries of Kanafani described him as an angry man, enraged by the loss of his homeland. This was a man who endured the humiliation and squalor of Palestinian refugee camps in Syria and Lebanon, who lived most of his years as a citizen of nowhere, shunted from country to country. It’s not surprising that Kanafani’s work reveals a deep pessimism, pessimism forged by a life lived in disappointment–dissapointment at Israeli Jews who expelled his family and forbad them from returning, disappointment at the Palestinian leadership for its feebleness, disappointment at the Arab states that largely failed to look after the flood of Arab arrivals. In 1960, Kanafani wrote in his diary, “The only thing we know is that tomorrow will be no better than today, and that we are waiting on the banks, yearning, for a boat that will not come. We are sentenced to be separated from everything–except from our own destruction.” In a sense, there is no better summation of his worldview.

Though the importance of the Israel-Palestine conflict in global politics and society has grown since the summer of 1972, the prospects of a peace for two peoples seems only to have diminished. As settlers nibble away land in the West Bank, and Gaza resembles a crater of the moon, the dream of a Palestine for Palestinians seems to be slipping, day by day, farther out of reach. Nevertheless, ideas are stubborn things, inhabited by people with passions, desires and irrationalities. The boat never came for Ghassan Kanafani, or for the millions of refugees of his generation who ended their days outside of Palestine. Yet around the world, in the West Bank and in Gaza, there are millions more Palestinians gathered along the banks, waiting.

In this post Baybars highlights the arty refugee experience of Kafani. He is a citizen journalist on a placement with us organised by Oxford University Career Services. He also organised the micro game to make the journalistic experience interactive.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gaming art here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.