From Refugee to Knighthood:The Untold Story with real life plots and twists.

Play & learn about Sir Tom Stoppard's arty refugee experience 🎮

Click here to play & learn.

Back Story

Sir Tom Stoppard, an extraordinary career, and an extraordinary life story

In his play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, Tom Stoppard has his player pronounce that “every exit is an entrance somewhere else.” Such would be a fitting summary of the early years of Stoppard’s own life.

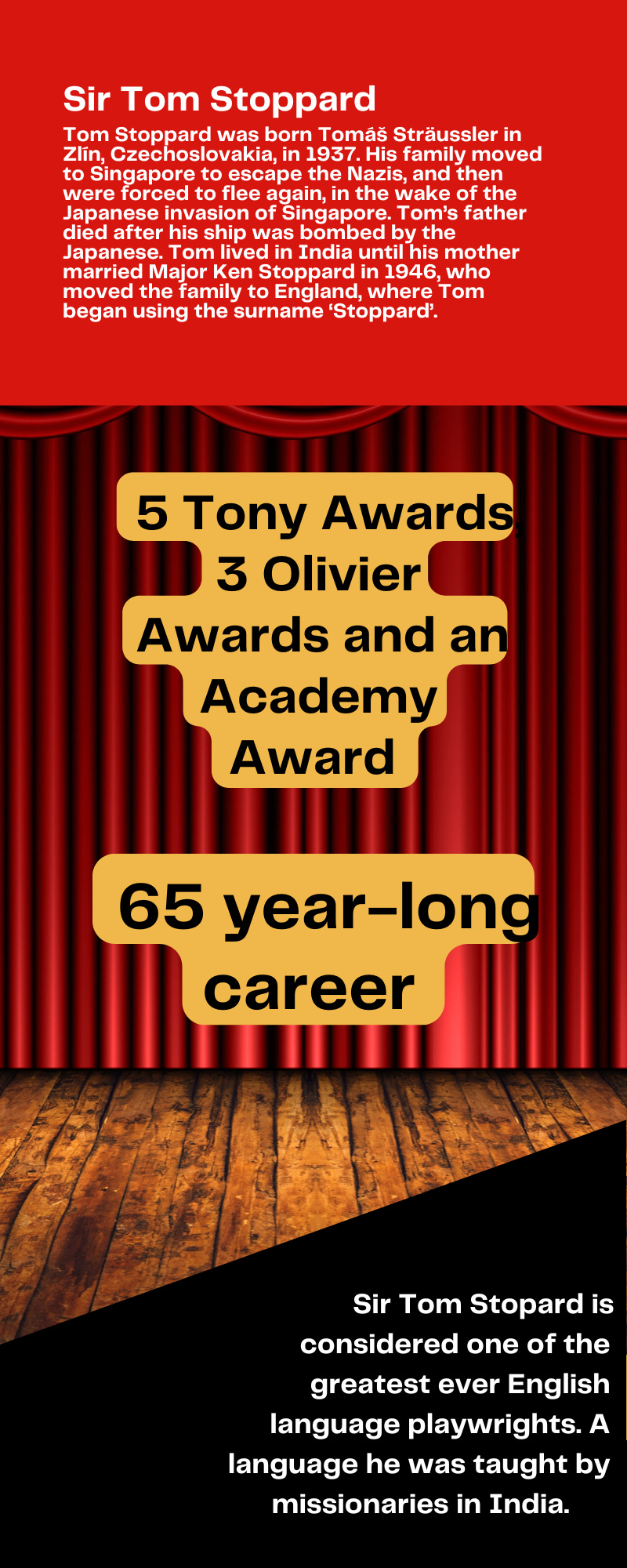

Tom Stoppard was born Tomáš Sträussler in Zlín, Czechoslovakia, in 1937. He lived comfortably there with his brother Petr and parents Marta and Eugen, a doctor employed by the Bata shoe company1. The family fled to Singapore in March 1939, the very same day the Germans invaded (though Stoppard’s own awareness of the correlation between these two events came much later on2).

After three years in Singapore, the Japanese invasion forced the family to flee again. Tomáš Sträussler and his mother and brother arrived in India, having boarded a ship they thought was headed for Australia. Stoppard’s father stayed behind as a volunteer doctor with the British army. He was killed by the Japanese, who bombed the boat he boarded to reach his family. Marta didn’t even know she was a widow when she arrived in India.

Stoppard claims he hasn’t “ever stopped dreaming about3” the time he spent in India. It was here that the young Stoppard, who would go on to become one of the most successful English-language playwrights of all time, was taught English by American Methodists in Darjeeling4.

His eventual journey to England came after Stoppard’s mother, Martha, married British army officer Major Kenneth Stoppard in 1946. Exit Tomás Sträussler, enter Tom Stoppard. He was sent to British boarding school to become, for all intents and purposes, an Englishman.

England certainly was the place that made the most immediate impression on Stoppard. “I just seized England and it seized me. Within minutes it seems to me, I had no sense of being in an alien land and my feelings for, my empathy for English landscape, English architecture, English character, all that, has just somehow become stronger and stronger.”5

Certainly tragic then, that Ken Stoppard, Tom’s stepfather, felt the need to remind Tom of the fragility of his English identity. As a child, he would probe “Don’t you realise that I made you British?” Ken even wrote to him after Martha’s death instructing him to stop using the Stoppard name. The name which had originally tethered him to the country where he is now a Knight.

No wonder then, that a young Stoppard felt uneasy as an “honorary Englishman.”6Admitting the vulnerability within his English identity, he said “I find I put a foot wrong—it could be pronunciation, an arcane bit of English history—and suddenly I'm there naked, as someone with a pass, a press ticket.”

In contrast, Professor Ira Nadel points out that Stoppard’s plays are in fact a celebration of Englishness, with their sparkling wit, portrayal of English habit, and masterful use of the English language. Certainly, English in their own right.7

Professor Paul Delaney notes that the theme of multiple identity runs through all of Stoppard’s work, and reflects something of how the playwright sees himself. His characterisation of unidentical twins also displays a concern with the possibility of us containing an elusive inner sense of self, that awaits to be revealed.

However, Stoppard had been seen as a writer who resisted the urge to draw on personal experience as part of the creative process. When asked about where he got his ideas, he would frequently respond “Harrods.”8 Perhaps, this stems from the fact that Stoppard only discovered the truth about his past late on in life. He titled a 1999 article ‘On turning out to be Jewish'.9

One reason for this, was his mother’s reluctance to discuss her ancestry. "Tsk!” her response, to the question of whether Stoppard’s family were Jewish. Stoppard feels as though their Jewishness was more defined by the family’s persecution than by their religious practises - “Hitler made her Jewish in 1939.”10

However, It is interesting to note the way in which his mother felt she had to, or at least that it was easier to hide her Jewish background in order to assimilate into her new life in Britain. Stoppard even remembers her asking “Why do they harp on about that? It’s got nothing to do with your life now. Can’t you stop them?” in response to acknowledgment by journalists of Stoppard’s background.11

His own experience of uncertainty in respect to the truth of his past surely explains why he chose to satire the work of biographers in more than one of his plays. In Arcadia, for example, biographer Bernard Nightingale has his theory about Byron overturned by the discovery of a passage that contradicts it. Instead, Stoppard displays a preference for reinvention. For him, invention is a facet of everyday life; he cites lying about the date when writing a thank-you card, and embellishing a story for comedic effect, as examples of the necessary of invention.

Furthermore, he has stated his belief that one’s conception of self-identity is not expressed consciously in writing but rather that “the writing instinct doesn't come out of self-examination. That part of yourself in your work is expressed willy-nilly, without your cooperation, motivation or collusion. You can't help being what you write and writing what you are."

When, in his early career, attempts were made to draw parallels between Stoppard’s own life, and the events of his plays, he quipped “I have to admit the stuff is there but I can’t for the life of me remember packing it.”12 Perhaps this is why few who met him as a young playwright had any inkling of the dramatic scenes of his childhood.

Later on, confrontation of identity became a visible theme in Tom’s oeuvre. He admitted that “The older I get, the less I care about self-concealment.”13 Much of Stoppard’s work from the 1970’s and 1980’s becomes increasingly concerned with politics. In Night and Day (1978), Dogg’s Hamlet, Cahoot’s Macbeth (1979) and Squaring the Circle (1984), Stoppard speaks out against Soviet abuse of Jewish dissidents and human rights violations in Czechoslovakia, as well as against limitations on journalists’ freedom of expression in Britain. 14

For Croatian writer Daša Drndić however, who criticised him in her novel Trieste, Stoppard15 had failed to acknowledge the suffering of his fellow Jews. Stoppard accepted this reproach16, having admitted himself that he felt he had lived a ‘charmed life17’ and in the wake of his own guilt, began work on Leopoldstadt.

It was in 2020, 60 years into his career that Tom Stoppard’s play, which takes its name from the old Jewish quarter of Vienna and follows a Jewish family who had fled pogroms in the East, premiered on the West End. He admitted that the play had been in the works for a long time, and that much of the material was personal to him18. All four of Stoppard’s grandparents were killed by the Nazis in concentration camps19. Although the play was initially forced to close due to the pandemic, it went on to win both the Olivier and Tony award for best new play.

Stoppard has admitted that one of the play’s characters Leo is ‘brazen self-pillage’20. Much like Leo, whose journey of self-discovery leaves him in tears, the 87-year-old admitted “I always cry, I keep thinking, I can’t keep doing this. I think it’s about the 10th time I’ve seen it.”21. The show’s producer Sonia Friedman said that the play had inspired her to hire a genealogist to investigate the fate of her own Jewish ancestors.

Although Stoppard rejects the idea that his own experience actively dictates that which he produces, it certainly seems like he is attracted to the story of the refugee. As a young writer, he produced a radio serial for BBC world service about a Palestinian medical student living in London called A Student’s Diary22. The year Leopoldstadt was released, Stoppard adapted The Voyage of the St Louis for the radio. The story of a German ocean liner carrying around 900 Jewish passengers fleeing persecution, few of whom succeeded as Stoppard did.

Bibliography

https://www.thejc.com/life/the-refugee-who-looked-back-at-last-dkmzr42b

https://www.huntingtontheatre.org/2024/09/11/tom-stoppard-on-turning-out-to-be-jewish/

https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2008/sep/06/stoppard.theatre

Paul Delaney “Exit Tomás Straüssler, enter Sir Tom Stoppard”

Paul Allen, Third Ear, BBC Radio Three, 16 April 1991, reprinted in Delaney, ed., Stoppard in Conversation, p. 246.

https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2008/sep/06/stoppard.theatre

https://muse-jhu-edu.ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/article/500576/pdf

Tom Stoppard, “On Turning Out to be Jewish,” Talk (September 1999), p. 243.

https://www.huntingtontheatre.org/2024/09/11/tom-stoppard-on-turning-out-to-be-jewish/

https://www.huntingtontheatre.org/2024/09/11/tom-stoppard-on-turning-out-to-be-jewish/

Tom Stoppard, quoted in Nightingale, 38. See note 2.

https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2013/oct/11/tom-stoppard-pen-pinter-lecture

https://www.thetimes.com/culture/article/leopoldstadt-tom-stoppards-new-play-lpbvn6cl2

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-new-yorker-interview/tom-stoppard-faces-his-familys-past

In this post Isabel highlights the arty refugee experience of Sir Tom Stoppard. She is a citizen journalist on a placement with us organised by Oxford University Career Services. She also organised the micro game to make the journalistic experience interactive.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.