Human Hair & Hot Spots: She Challenges Norms, Paints the Unseen. ✨💔

Read, Listen, Play & learn about Mona Hatoum's arty refugee experience 🎮

Click here to play & learn.

Back Story

Mona Hatoum is a London-based artist and refugee, born into a Palestinian family in Lebanon. She was later forced into exile to the UK. Her work centers around themes including, but in no way limited to, conflict and cultural contradiction. The thought-provoking messages ingrained in Hatoum’s art reflect her response to her cultural background and polycultural identity, with the artist’s performance pieces, photography, paper works, and installations utilising art as a medium to explore female sexuality and violence within institutional power structures.

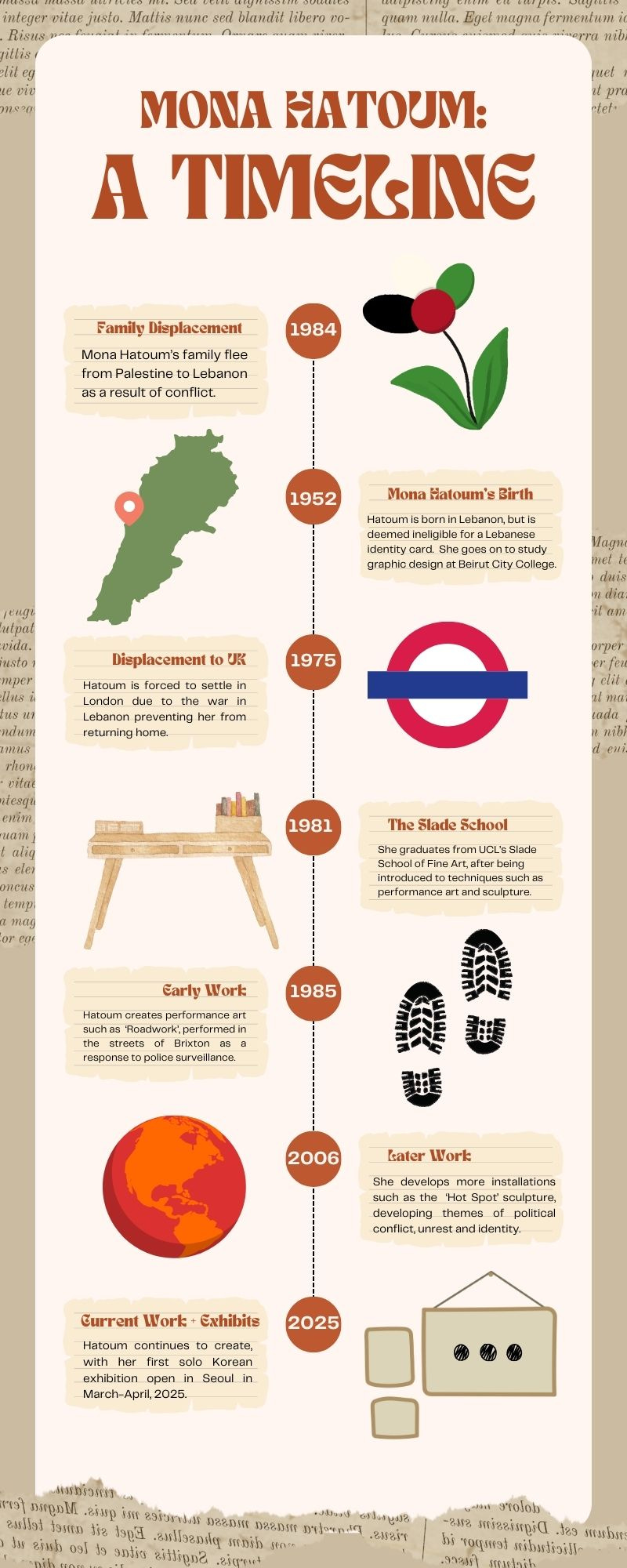

Hatoum’s early experiences and the context that surrounded them came to fuel many of the artist’s later creations. Before she was born, Mona Hatoum’s family were exiled from Palestine to Lebanon in 1948. This was due to brutal conflict in their home region: On the 29th November 1947 the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was adopted in the Middle East, which proposed that the state of Palestine should be divided into an Arab state, a Jewish state, and a Special International Regime that included the cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem. However, the day after this adoption, the civil war began. Beginning in April 1948, Zionist forces began a series of offensives inside of Mandatory Palestine, with the aim to establish a Zionist Jewish state. This led to the 14th May Israel Declaration of Independence. Further, on the 15th May 1948, Iraqi forces then entered Palestine, taking control of the assigned Arab areas and launching offences on Israeli bases. This series of conflicts resulted in many citizens being killed or exiled from Palestine, with Hatoum’s family fleeing to Lebanon in search of safety.

After her birth in 1952, Mona Hatoum was deemed ineligible for a Lebanese identity card, which the artist more recently claimed was ‘discouraging [her] from integrating into the Lebanese situation.’ Today, over 470,000 Palestinian refugees have been exiled to Lebanon, and Palestinians in Lebanon still have limited legal rights, with barriers that prevent them from accessing employment and services. Still, despite her family’s initially unsupportive approach to Hatoum’s ambition to pursue a career in art, she studied graphic design at Beirut City College and went on to pursue a self-proclaimed unfulfilling graphics career. However, after visiting the UK for what was meant to be a brief period of 1975, Hatoum was forced into exile in London as the war in Lebanon broke out.

On the 13th April 1975, conflict between the Palestinian Liberation Organisation and the Kataeb Christian Militia reached Beitrut, resulting in citywide conflict. Then, in December 1975 as a response to attacks, roadblocks were set up through Beitrut, with passer’s identification cards checked for religious affiliations. Many Palestinian or Lebanese Muslims were killed when stopped for their identification. This war led to the exodus of over one million people from Lebanon, and over 150,000 fatalities during the period of 1975-1990.

Despite being displaced from the city she grew up in, Hatoum’s artistic spirit did not waver. In London she studied at UCL’s Slade School of Fine Art, which boasts other famous alumni including David Bomberg and Stanley Spencer. According to Hatoum, her early-life experiences founded a ‘kind of dislocation’ in the mind of her as the artist, which then came to manifest itself in the artwork she creates.

Hatoum’s artwork has been showcased internationally, featured in installations at the Tate Modern and White Cube in London, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Rejecting any monist interpretation of her art, Mona Hatoum encourages viewers to come up with their own responses alongside the personal intentions that she encodes in the making of her art.

Hatoum’s earlier work consisted of performance pieces that are arresting and unafraid of sparking controversy. After being introduced to the mode of art during her time at the Slade School, Mona Hatoum produced iconic pieces such as ‘Roadworks’. Performed in Brixton in 1985, the performance piece aimed to encourage the viewer to confront the police surveillance of the Afro-Caribbean residents in the area. Hatoum walked through the streets of Brixton with heavy black boots tied to her ankles, directly responding to the events of the 1985 Brixton uprising. She noted that, in reference to ‘Roadwork’ her work is ‘personal/ autobiographical’ yet it simultaneously has ‘an immediate relevance to the community of people it was addressing.’

In a piece for the Guardian, Hatoum admits that ‘doing performance art was a way of working well away from the shadow of males,’ this admission representing the themes of womanhood and femininity that she goes on to explore in later works. Indeed, ‘Roadwork’ was curated as part of the 2023 Women In Revolt exhibit at the Tate Britain.

As well as developing performance art, Hatoum turned to photography in her early work: ‘Measures of Distance.’ This was developed in 1988, going on to be screened at Montreal Women’s Film and Video Festival, engaging with themes of both displacement and intimate female sexuality. The video is composed of intimate photo-shots of Hautoum’s mother, alongside Arabic and English narration drawn from hand-written letters. The piece expresses a profound feeling of deep loss which arises as a result of separation caused by war, drawing uncharacteristically directly on Mona Hatoum’s personal experiences of conflict and how it affected both her identity and relationships. By presenting the viewer with a Palestinian woman, her mother, she gives a marginalised woman a voice.

During her later works, Hatoum continued to develop the themes above, using object installations: her 1993 piece ‘Keffieh’ is a scarf woven of human hair, to contrast Hatoum’s ideas around religion, Palestinian culture, and womanhood. Often used as a symbol of health and beauty, hair is a human product, and weaving is typically an activity aligned with feminine social roles. The delicate pattern woven in ‘Keffieh’ has come to be politically synonymous with support for Palestine, exploring the experience of women who have grown up immersed in struggling.

Hatoum’s sculptural piece, ‘Hot Spot’ refers back to places of military unrest using red neon wire to create the edges of the Earth’s continents–-hot spots. The sculpture is large, approximately the height of a person, and visually confronts the viewer with their ideas of boundaries. The red glow coming from the orb-earth, I interpret at least, as a warning of the consequences of global unrest; what Mona Hatoum describes as ‘a world continually caught up in conflict and unrest’. The piece was exhibited in the iconic modern art gallery, White Cube in Bermondsey in 2006, and later in 2013 under the title ‘Hot Spot III’.

By ingraining the notions of different types of tension, cultural contradiction, and by reflecting on her life experiences in performances and installations, Mona Hatoum makes detailed ‘human studies related to political conflict, global inequity, and being an outsider.’As demonstrated throughout her body of work, Hatoum uses that feeling of ‘dislocation’ she identified as fuel for creation of art that is both powerfully personal, and universally political. As recognition of her artistic skill, Hatoum has received, amongst other accreditations, the Joan Miro Prize (2011) and the 10th Hiroshima Prize (2017).

Bibliography:

Antoni, Janine, BOMB Magazine, 1998

Byman, Daniel, and Kenneth Michael Pollack. Things Fall Apart: Containing the Spillover from an Iraqi Civil War, p. 139

Mixed Migration, Lebanon conflict Displacement Migration Consequences, 2024

The Guardian, Mona Hatoum: ‘Each person is free to understand what I do in the light of who they are and where they stand, 2016

Sanctuary, FOR-SITE Foundation, 2017

UN Human Rights Council, "IMPLEMENTATION OF GENERAL ASSEMBLY RESOLUTION 60/251 OF 15 MARCH 2006 ENTITLED HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL.", 2006, p.18

White Cube Gallery, Gallery Exhibitions, Hot Spot, 2013

In this post Phoebe highlights the arty refugee experience of Mona Hatoum. She is a citizen journalist on a placement with us organised by Oxford University Career Services. She also organised the micro game to make the journalistic experience interactive.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.