Kafka's Successor? He Defied Dictators With Hidden Stories.

Play & learn about Ismail Kadare's arty refugee experience 🎮

Click here to play & learn.

Back Story

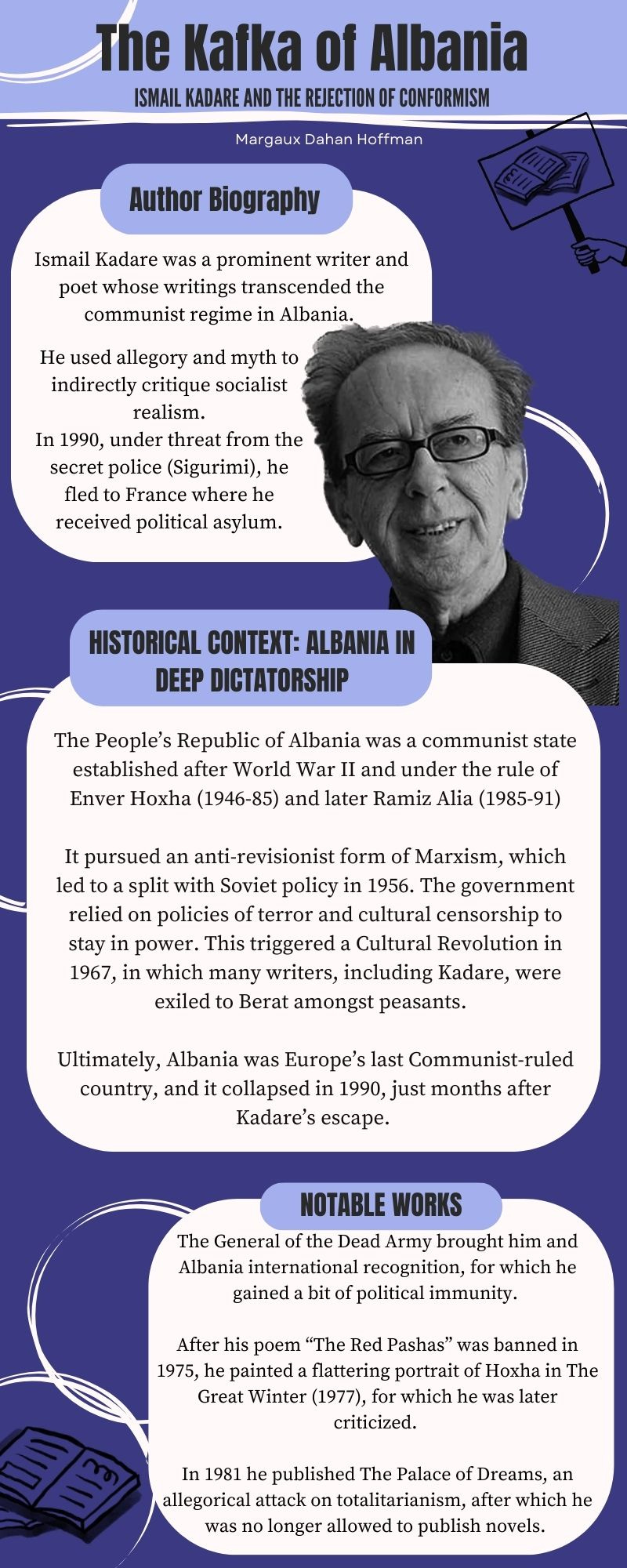

If America claims Mark Twain as one of its greatest writers – with William Faulkner going as far as to call him “the father of American literature” – then Albania has Ismail Kadare. The writer, poet, and journalist spent decades criticizing the Communist regime in which he lived and incarnating Albanian national identity. In 1990, after years of criticism of the Albanian government and multiple bans, and in light of a possible arrest, Kadare sought political asylum in France.

Kadare was born in Gjirokastër in 1936 – a city which would go on to inspire his works. As a boy, he experienced the invasion of Albania by the Italian forces during the Second World War, and the rapid shift to a Communist regime under the rule of the Stalinist dictator Enver Hoxha in the postwar era. This regime was characterized by forced collectivization, surveillance, and the erasure of any dissidence, notably through cultural censorship. This new world shaped Kadare’s work.

Gifted and precocious, Kadare began writing from a very early age. At 17, he won a poetry competition in Tirana and was granted the opportunity to study literature at the Gorky Institute in Moscow. There, he witnessed firsthand the workings and influence of a communist regime in cultural affairs and the silencing of dissident intellectuals. He was disillusioned by writings of Socialist Realism - the official doctrine that dictated that all art should glorify the myth of the Socialist regime, and serve as a tool in the building of socialism and patriarchal sentiments of the masses. Kadare vowed to write against such dogmatism and the conformism that the Communist regime demanded. To him, literature was a force for truth, as he once wrote: “Faith in literature and in the creative process brings protection. It generates antibodies that allow you to struggle against state terror.

At the time of his writing, Albania had become one of the most isolated countries in Europe, sealed off by Hoxha’s brutal Stalinist policies. Hoxha was a vehement Stalinist, and developed a strong policy of political repression by the secret police, the Sigurimi. Kadare was unable to criticize the regime directly. Instead, he used literary devices such as satire, parable, allegory, myth, and magical realism to critique the regime and explore Albania’s cultural identity. His genius lay in his ability to craft stories set in distant histories, myths, and Balkan folk tales while embedding them with sharp critiques of contemporary Albanian society. Notably, he used the Ottoman Empire as a stand-in for the present-day situation, allowing him to circumvent censorship and deliver his message to domestic and international audiences.

Kadare initially was fruitful in his literary career. One of his early works, The General of the Dead Army (1963), was an international success. It was the story of an Italian general and a priest who went to Albania to repatriate the bodies of fallen soldiers after World War II. The book was criticized domestically for flouting socialist ideals and critiquing the Communist regime. For many critics, he was an ‘agent of the West’ – possibly one of the most damning things to be accused of at the time. The international profile, however, offered him some protection, as his novel represented some national pride, even though it did not conform to Socialist Realism.

As Kadare's reputation grew, so did the scrutiny of his work. In the 1970s, his criticism of the regime became increasingly explicit. In 1975, Kadare published “The Red Pasha”. The satirical poem poked fun at the Albanian Communist bureaucracy. As a result, the poem was banned and he was denounced, nearly shot, and ultimately sent to do manual labor in the Albanian provinces. Following this incident, Kadare was subject to greater repression. Many of his works were banned or unable to be published under the regime. He was under constant surveillance by the Sigurimi. Despite this, Kadare continued to write, and even smuggled his works abroad with the French translator for publication.

In 1977, Kadare published the controversial novel The Great Winter. The novel dramatizes Albania's break with the Soviet Union in 1960. Hoxha is portrayed as a national hero for his defense of Nikita Khrushchev. For many critics, this was proof of Kadare’s collaboration with the regime, in spite of the anti-totalitarian spirit of the rest of his work. He claimed that the publishing of this novel was for pragmatic purposes: the protection that international acclaim had granted him was wearing thin, and he had to prioritize his survival under socialism to dissidence.

Both Broken April (1978) and The Palace of Dreams (1981) bypassed censors, despite being thinly veiled criticisms of totalitarianism. Broken April is a story about the blood feuds that continue to haunt Albania, and explores the ways in which political power perpetuates cycles of violence. It’s an assertion of Albanian identity in the face of Hoxha’s attempt to replace this with the ideological Stalinist figure of the “new man. Meanwhile, The Palace of Dreams is a political novel in the tradition of Orwell and Kafka, about a state-run institution that manipulates the dreams of the population in order to control their actions. The novel was banned almost immediately after its publication and Kadare was forbidden to publish book-length novels thereafter.

After The Palace of Dreams, Kadare’s situation was even more difficult. He faced greater criticism and feared the intensification of the regime that would occur when Enver Hoxha was replaced. Upon discovering that he had been marked, along with 100 other writers, for arrest, Kadare sought asylum in France in 1990, where he was granted citizenship immediately.

Kadare's move to France marked a new phase in his literary career. He was able to write more directly about the Albanian regime. Notably, he published The Blinding Order, in which he explored the psychological and social effects of absolute power, depicting an Ottoman sultan who decrees that those with the "evil eye" must be blinded. Similarly, in The Pyramid, he critiqued the construction of monumental projects as a means for oppressive rulers to reinforce their control over their subjects.

Throughout the 1990s and into the 21st century, Kadare’s international reputation continued to grow. He became one of the most celebrated authors of his generation, earning numerous prestigious awards, including the 1992 Prix Mondial Cino Del Duca and the 2005 Man Booker International Prize. In 2020, he was awarded the Neustadt International Prize for Literature. In his nomination, the juror wrote that “Kadare is the successor of Franz Kafka. No one since Kafka has delved into the infernal mechanism of totalitarian power and its impact on the human soul in as much hypnotic depth as Kadare."

He was still intrinsically tied to his homeland, and once the communist regime had given way, he returned to Tirana, living between Albania and Paris. In his later works, publishing autobiographical works such as Invitation to the Writer's Studio (1990), The Weight of the Cross (1991), and The Doll (2015). These works served as reflections on his homeland and the legacy of Albania's history of political repression, as well as serve as record-setters for his actions under the regime.

Ismail Kadare’s literary legacy endures as a testament to the power of the written word against tyranny. His ability to craft stories that resonated with both the political and the human experiences, especially in a period of near-impossible everyday life under this oppressive regime, secured his place among great writers of Albania and the 20th century. Kadare’s works continue to resonate today, inspiring dissidence against repressive governments and the censorship of the truth.

Bibliography:

“Ismaíl Kadaré: Prince of Asturias Award for Literature 2009.” Fundación Princesa de Asturias. https://www.fpa.es/en/princess-of-asturias-awards/laureates/2009-ismail-kadare/?texto=trayectoria&especifica=0 Accessed 25 March, 2025.

“2020 - Ismail Kadare: Winner of the 2020 Neustadt International Prize for Literature.” The Neustadt Prizes. https://www.neustadtprize.org/2020-ismail-kadare/ Accessed 25 March, 2025.

Bellos, David. “Why Should We Read Ismail Kadare?” World Literature Today, Vol. 95, No. 1, 2021, pp. 54-55.

Bellos, David. “Ismail Kadare obituary.” The Guardian, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/jul/01/ismail-kadare-obituary Accessed 25 March, 2025.

Binder, David. “Albanian Exile Writer Sees Reform.” The New York Times, 1990. https://www.nytimes.com/1990/12/06/world/albanian-exile-writer-sees-reform.html Accessed 25 March, 2025.

Elsie, Robert. “Evolution and Revolution in Modern Albanian Literature.” World Literature Today, Vol. 65, No. 2, 1991, pp. 256-263.

Lea, Richard. “Ismail Kadare, giant of Albanian literature, dies aged 88.” The Guardian, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/books/article/2024/jul/01/ismail-kadare-giant-of-albanian-literature-dies-aged-88?CMP=share_btn_url Accessed 25 March, 2025.

Manguel, Alberto. “‘An ancient shadow permeates his work’: Alberto Manguel on the genius of Ismail Kadare.” The Guardian, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/books/article/2024/jul/01/an-ancient-shadow-permeates-his-work-alberto-manguel-on-the-genius-of-ismail-kadare Accessed 25 March, 2025.

Morgan, Peter. “Ismail Kadare: Modern Homer or Albanian Dissident?” World Literature Today, Vol. 80, No. 5, 2006, pp. 7-11.

Murray, John. “Books: The Orphan’s Voice.” Independent, 1998. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books-the-orphan-s-voice-1140904.html Accessed 25 March, 2025.

Zerofsky, Elisabeth. “Ismail Kadare Attributes His Writer’s Gift to His Mother.” The New York Times, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/17/books/review/ismail-kadare-doll.html Accessed 25 March, 2025.

In this post Margaux highlights the arty refugee experience of Ismail Kadare She is a citizen journalist on a placement with us organised by Oxford University Career Services. She also organised the micro game to make the journalistic experience interactive.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.