Hidden yet Entrenched Inequalities in Higher Education Post-Apartheid: Black South African Women and the Legacy of Racial Conflict.

Introduction

“Educate a woman, you educate a nation.” These powerful words were spoken by Deputy President Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka at the 4th annual Women’s Parliament Conference in Cape Town. Her statement reflects the South African government’s commitment to increase women’s access to higher education since the end of Apartheid in 1994 (Eynon, 2017).

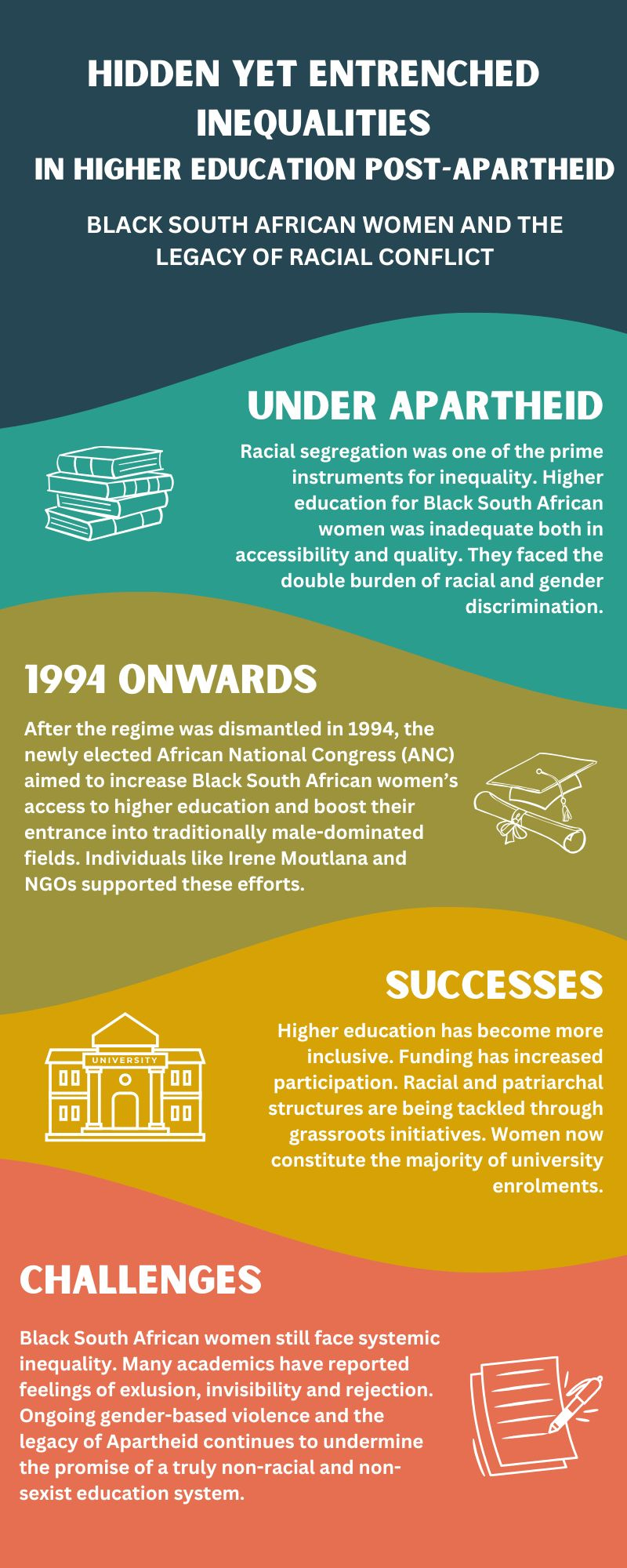

Apartheid, meaning ‘apartness’, was the Afrikaans name given by the white-ruled South African Nationalist Party to their institutionalised system of racial segregation. Although the regime was established in 1948, many segregationist policies dated back to the early decades of the twentieth century. Over thirty years since the end of Apartheid, Black South African women still grapple with the legacy of racial conflict, especially in higher education.

Higher education for Black South African women has transformed since 1994. Affirmative action, scholarships and support programs have been pivotal in overcoming systemic barriers. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and inspiring individuals such as Irene Moutlana have supported such efforts. However, there have been numerous drawbacks.

Despite legislation, initiatives and policies since 1994, the higher education system is still struggling with many of the same issues it faced in the late 1990s. Access and participation, affordability and funding, student preparedness, racial relations on campus, institutional cultures and language are some of the most pressing. The root of these problems lies in the discriminatory conditions of segregation and repression under Apartheid, revealing that hidden, yet entrenched, inequalities still persist. This article will assess the successes and challenges of Black South African women’s higher education post-Apartheid.

For Black South African women, the classroom was another site of oppression

During Apartheid, racial discrimination deeply influenced society, leading to widespread inequalities. The education system was segregated by race under the Bantu Education Act of 1953 and the Extension of University Education Act of 1959. This limited educational and professional opportunities for Black South Africans. In particular, Black South African women faced the double burden of racial and gender discrimination, which significantly limited their socioeconomic development.

There were great disparities in spending between Black and white education. The Nationalist Party financed white education liberally, while consistently underfunding Black education. In 1988, per capita expenditure was R3,983 for white pupils and R583 for Black pupils. Inadequate school provisions led to poor facilities, under-qualified teachers and insufficient classrooms, as well as high levels of illiteracy. This coincided with a high drop-out rate, with Black South African girls in senior secondary school in 1985 making up only 15.8% of those enrolled in the lowest grades 15 years before (Unterhalter, 1990). As a result, the number of Black South African women entering higher education remained extremely low, revealing how segregation was one of the prime instruments for inequality.

The racial imbalances in South African higher education worsen when gender is added to the equation. Most Black South African women were enrolled in part-time courses in education, languages, the social sciences and humanities. In 1991, only 6% were enrolled in engineering at the nation’s institutes of technology called ‘Technikons’ (Martineau, 1997). These statistics reflect severe gender inequalities in areas of science, engineering and technology, subjects that the South African economy depended on. This afforded men more prestige and power, while women were less likely to greatly alter their position in the labour force or society.

Targeted initiatives are narrowing the education gap, but challenges remain

Creating a system that provides quality education and training for all, regardless of race, class or gender, was one of the greatest challenges facing the South African government in 1994. Post-Apartheid reforms aimed to increase Black South African women’s access to higher education and substantially bolster their entrance into traditionally male-dominated fields.

The African National Congress (ANC) took office in April 1994 after South Africa’s first democratic, multiracial elections. The new government introduced various initiatives for a nonracist and non-sexist educational environment. The Bill of Rights under the Constitution of 1996 specified the government’s responsibility to make education accessible to all and redress racial discrimination. The appointment of women to senior government positions and the enactment of laws, such as the Higher Education Act of 1997, also ensured the equitable treatment of historically excluded groups under the law – Black South Africans and women.

Black South African women have also played a pivotal role in improving the accessibility and quality of education. Irene Moutlana is a leading example. Vice Chancellor and Principal at the Vaal University of Technology (VUT), Moutlana is a central figure in the South African higher education system. Under her leadership, VUT has transformed from an institution known for low academic standards to one offering education on par with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). VUT has received awards for their management of the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) funds during Moutlana’s tenure (Eynon, 2017). This has both accelerated Black South African women’s entry into higher education and into traditionally male-dominated fields, which has reduced the education gap at VUT.

NGOs are also building a sustainable future. Sonke Gender Justice is a prominent example. A significant barrier to women’s academic success is gender-based violence (GBV) on campus, which has disproportionately affected Black South African women. By partnering with universities and advocating gender equality, Sonke Gender Justice is helping to create safer, more supportive environments for women in higher education. Under patriarchal structures, higher education institutions remain geared towards the production of masculine privilege. This means that women find themselves victimised in the very system that is supposed to be promoting civility and knowledge (Eynon, 2017). Sonke’s promotion of male involvement in preventing GBV at the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Cape Town (historically white universities) has been crucial in dismantling these patriarchal attitudes, eliminating discrimination, pioneering structural change and social cohesion.

Today, women constitute most of the student population at many universities. According to the Council on Higher Education, women made up 58% of university enrolments by 2018. However, the legacy of Apartheid still persists. While the percentage of Black South African women with no education has halved since 1994, from 28% to 14%, this is drastically higher than the 1% of white women without any education. Furthermore, many female Black South African academics experience feelings of exclusion, invisibility and rejection due to historical factors, alongside systemic and institutionalised reasons for inequality.

In addition, students at Rhodes University protested the continued presence of colonial and Apartheid forces in higher education under the #FeesMustFall movement in 2015. The chant “Asiphelelanga” (translating to “We are not complete” from Zulu) asserts that South Africa’s liberatory project is incomplete (Chéry, 2023). This encapsulates that the promise of a truly non-racial and non-sexist democracy is yet to be fulfilled.

Conclusion

The rise of Black South African women in higher education is a story of transformational change. Historically marginalised and excluded due to colonial and Apartheid-era policies, women now comprise the majority of students in South Africa’s higher education institutions. This evolution demonstrates the fundamental importance of policy intervention, advocacy and NGOs in achieving true equality in not only higher education, but broader society.

However, the legacy of racial conflict remains. It is vital to understand the many complex challenges that women continue to face in South Africa’s higher education system. This reveals how the discriminatory architecture of the past continues to influence the present, underscoring why efforts to tackle them are therefore of critical necessity.

Bibliography

Chéry, Tshepo Masango, ‘“Asiphelelanga!” (We are not complete!): #FeesMustFall movement and higher education in post-apartheid South Africa’, Safundi, 24 (2024), 239-265.

Eynon, Diane E., Women, Economic Development, and Higher Education: Tools in the Reconstruction and Transformation of Post-Apartheid South Africa (Cham, 2017).

Mabokela, Reitumetse Obakeng, ‘Hear Our Voices!: Women and the Transformation of South African Higher Education’, Journal of Negro Education, 70 (2001), 204-218.

Martineau, Rowena, ‘Women and Education in South Africa: Factors Influencing Women’s Educational Progress and Their Entry into Traditionally Male-Dominated Fields’, Journal of Negro Education, 66 (1997), 383-395.

United States Department of State, ‘The End of Apartheid’. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1989-1992/apartheid.

Unterhalter, Elaine, ‘The Impact of Apartheid on Women’s Education in South Africa’, Review of African Political Economy, 48 (1990), 66-75.

In this episode Senem discusses the aftermath of Apartheid and the struggle women are facing trying to gain an education. She is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Department of War Studies, King’s College, London. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.