The Issues facing Syrian Refugees

The fall of Syria’s President, Bashar al-Assad, and the regime which he led, brings hope to Syrian refugees. According to the UN, around 7.2 million Syrians have been internally displaced, with another 5.5 million fleeing the country. Whilst the political situation in Syria remains unclear, there is a strong desire to return for some Syrians.

Why do Syrians want to return?

Muhamad Mowakket, a humanitarian worker forced to leave Aleppo with his wife in 2014, articulates: “No one wants to be a refugee. No one chooses to be a refugee. No one likes it. We had a wonderful country.” His sentiment of returning to a place where you are no longer a refugee is repeated in many interviews with Syrian refugees. A Syrian family interviewed whilst waiting to cross into Syria at the Turkish border say “We have no one here. We are going back to Latakia, where we have family”. Other reports from the Türkiye-Syria border show children wrapped in Syrian flags, a clear sign of the love of their homeland, even though it is likely some of these children may have never been to Syria, being born after their family fled. Many Syrians in Turkey work below the minimum wage, and often have no insurance. For Syrians, some of whom left Syria over a decade ago, abandoned homes, nation and family are all important reasons for returning. There is also the urgent need to try and find family and friends who have gone ‘missing’ or have been imprisoned under Assad’s regime. Verified videos show groups of people searching the infamous Saydnaya prison, a place known for torture and mass imprisonment, looking for people they know who were imprisoned there. Both internally displaced refugees and refugees in other countries will be prioritising trying to find the people who have gone missing under the regime.

Many Syrian refugees have expressed the need they feel to go back to Syria to help rebuild and stabilise the Syrian nation in the longer term. Malak Matar, a Syrian refugee preparing to return, said that “Syrians have to create a state that is well-organised and takes care of their country. It’s a new phase.”. Similar sentiments are echoed on the Turkish-Syrian border: “As the Syrian people, we will try to rebuild everything little by little.”, saying that the identity of Syria’s next government is less important than Syrians going home to influence their future. Certainly, as Syria now experiences a power vacuum, refugees feel the need to help support their country in its rebuilding.

What are the challenges faced by refugees returning to Syria?

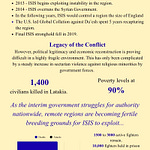

The most immediate problems for refugees looking to settle back into Syria is dealing with the destruction of the war, which has destroyed buildings, infrastructure, national services and the balance of power. The UN has estimated that at least 328,000 dwellings have been destroyed over the course of the war, with 13.6 million residents lacking access to clean water, hygiene and sanitation. For refugees returning, there is the possibility that they can no longer live in their homes they fled, and the damage the conflict has done to the sewage and power networks make the prospect of immediately returning a difficult one. With over 40% of hospitals not fully functional in Syria in 2023, as well as around 2 million children out of school and 7000 damaged schools, key infrastructure is not in a stable position in Syria to accommodate the return of its people. Unexploded mines and bombs also pose a great threat to refugees wanting to return. This follows the UN’s advice to Syrian refugees not to return to Syria due to the unsafe and precarious nature of the region.

The other major concern for Syrian refugees is the future of Syria’s government. The newly appointed temporary Prime Minister, Mohammed al-Bashir, is the leader of HTS, the main group responsible for the quick toppling of Assad’s regime. Whilst al-Bashir and HTS have gone through what has been described as a ‘rebranding’, Bashir was working for the terrorist organization al-Qaeda until he broke off with them in 2016. Some fear the beginning of an Islamist government, which could threaten the position of non-Muslim Syrians such as Druze and Maronites as well as ethnic minorities such as the Kurdish people, along with Syrian women. Others fear the retaliation of loyalist forces working under Assad, which could lead to another civil war.

How have foreign countries reacted to the changes in Syria, and how does this effect Syrian refugees wanting to return?

Turkey, which is currently home to over three million Syrian refugees, has expressed encouragement for the return of refugees to Syria. Migration expert Professor Murat Erdogan has articulated concern that if Syrians are not able to safely return to Syria in the coming months, a “new atmosphere of tension may emerge” between Syrian refugees and the Turkish people. The rising economic crisis in Turkey has meant that the past few years have seen a rise in anti-refugee sentiment, contributing to a hostile atmosphere towards some Syrians. This anti-refugee sentiment is prevalent in Europe too, especially as more recent European governments have seen a movement towards the right wing. In a recent EU meeting, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni urged EU leaders to explore strategies to enable the return of Syrian refugees, despite the UN’s official advice that Syria is still unsafe for refugees to return to. Countries including Germany, Austria, Belgium, Greece, Italy, Sweden, Denmark and the United Kingdom have paused the processing of Syrian asylum claims since the fall of Assad’s government, with the implication that there is no basis for Syrian refugees to be given asylum anymore. Both Turkey and Europe’s reaction place Syrian refugees in a hard position, where it is unclear whether Syria is safe to return to, and governments do not judge the situation in Syria to be dangerous enough anymore, contradicting UN advice. Further concerns for refugees include the threat of voluntary repatriation, where a refugee who returns to the country they fled from can be expelled from the country they have claimed asylum in. This is a particular issue due to Syria’s current political instability, where returning refugees may find that they can no longer live in Syria due to government or infrastructure issues, but are denied a return to their countries of asylum. For Syrian refugees who have settled in foreign countries and wish to continue their lives there, the prospect of going back to look for family members or abandoned property also contains the danger of not being let back into the new countries they have settled in.

In this episode Ella discusses Syria and it’s post conflict concerns. She is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Oxford University Career Services. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.