From Battlefront to Homefront: The Epidemic of Gender-Based Violence in Post-Conflict Iraq

An epidemic of gender-based violence has emerged in the aftermath of a long period of violent conflict in Iraq. For decades, Iraq experienced intense conflict, from the Iran-Iraq war to the Gulf Wars, and the conflict with ISIS. Despite there no longer being an armed threat to life, women and girls continue to be traumatised by fear and subjugation in their day-to-day lives.

According to UNICEF, 1.32 million people in Iraq are at risk of gender-based violence, with 75% of them being women and girls. UNICEF defines gender-based violence as “physical, sexual, mental, and economic harm inflicted on a person because of socially constructed power imbalances between males and females.” This includes sexual violence and trafficking, intimate partner violence, honour crimes, and child marriage. Survivors of gender-based violence experience long-term physical and psychological consequences and are frequently blamed for their abuse (Rfaat, 2021). The law in Iraq, known as the Iraqi penal code, lacks sufficient legislation to protect women and girls from violence and to hold their abusers accountable. This raises the question of why gender-based violence increases in post-conflict communities?

War exaggerates the concept of masculinity due to the re-establishment of traditional gender roles during conflict. Women become more situated within the domestic setting whilst men are more likely to take up arms. Because of this, violence becomes normalised and encouraged to men, creating a problem when the time comes to transition back into peaceful society. The power imbalance between men and women is amplified which leads to an increase of gender-based violence. The armed threat to life may have come to a close; however, women continue to live in fear for their safety (Puttick, 2024).

Legislation failures

Iraq’s legal framework stands as a clear enabler of the epidemic of gender-based violence. The Iraqi penal code is filled with exceptions that fail to adequately protect women and girls in Iraq and, in many cases, gives the power to the abusers. Article 41, for instance, legally allows a husband to punish his wife and parents their children using physical punishment. Despite the penal code’s stated criminalisation of sexual assault, exceptions exist that enable rapists to avoid prosecution by simply marrying their victims (Iraq: Penal Code). This strips women and girls of their autonomy and gives the power to their abuser as well as automatically excusing them for their crimes.

Article 409 stands as another clear failure within the Iraqi penal code. It grants men who murder or assault their female family members more lenient sentences as the legal system accepts the need to uphold family honour as a mitigating factor for these crimes, known as ‘honour killings’ (ibid). These exceptions within the penal code create the idea that gender-based violence is justifiable and acceptable as it does not sufficiently punish the abusers. It further endangers women because it fails to hold perpetrators accountable for their actions.

Tiba al-Ali was a 22-year-old YouTuber from Iraq who had grown a following by making videos about her life, with many videos featuring her fiancé. In January 2023, she returned to Iraq to visit her family after moving to Turkey. During her stay, police had attempted to intervene in a heated argument between Tiba and her father. Following this, Tiba was strangled to death in her sleep by her father who disagreed with her decision to move to Turkey and marry her Syrian-born fiancé. Her father later turned himself into the police, but was only sentenced to six months in prison (O’Reilly, 2023). Tiba was failed by the legal system as she did not receive justice for her killing or protection when she was alive.

This case is among many other honour killings, with the Iraqi penal code allowing for a mitigated sentence. The UN estimated that 5,000 women and girls across the world are murdered by family members each year in honour killings (United Nations, 2018).

Tiba al-Ali’s case resulted in uproar among Iraqi women who participated in protests in Baghdad against honour killings and the legal justifications that prevent justice (O’Reilly, 2023). The Iraqi penal code permits the mitigation of sentences on grounds of honour for violence against family members. This enforces the idea that victims are responsible for their own deaths because they are doing something that brings shame to their families. It is a misogynistic view built from years of false ideas about male superiority and the subjugation of women - a means to control women and girls.

The Kurdish Region of Northern Iraq

The Kurdish Region of Northern Iraq (KR-I) is a semi-autonomous region under the authority of the Iraqi government. However, they are able to pass laws that are applicable within the region. They have improved legal structures in place, such as the reversal of provisions in the Iraqi penal code that granted mitigated sentences for honour killings and allowed the corporal punishment of wives and children (Amnesty International, 2024a). However, these changes are arguably just on paper, with reality looking much different.

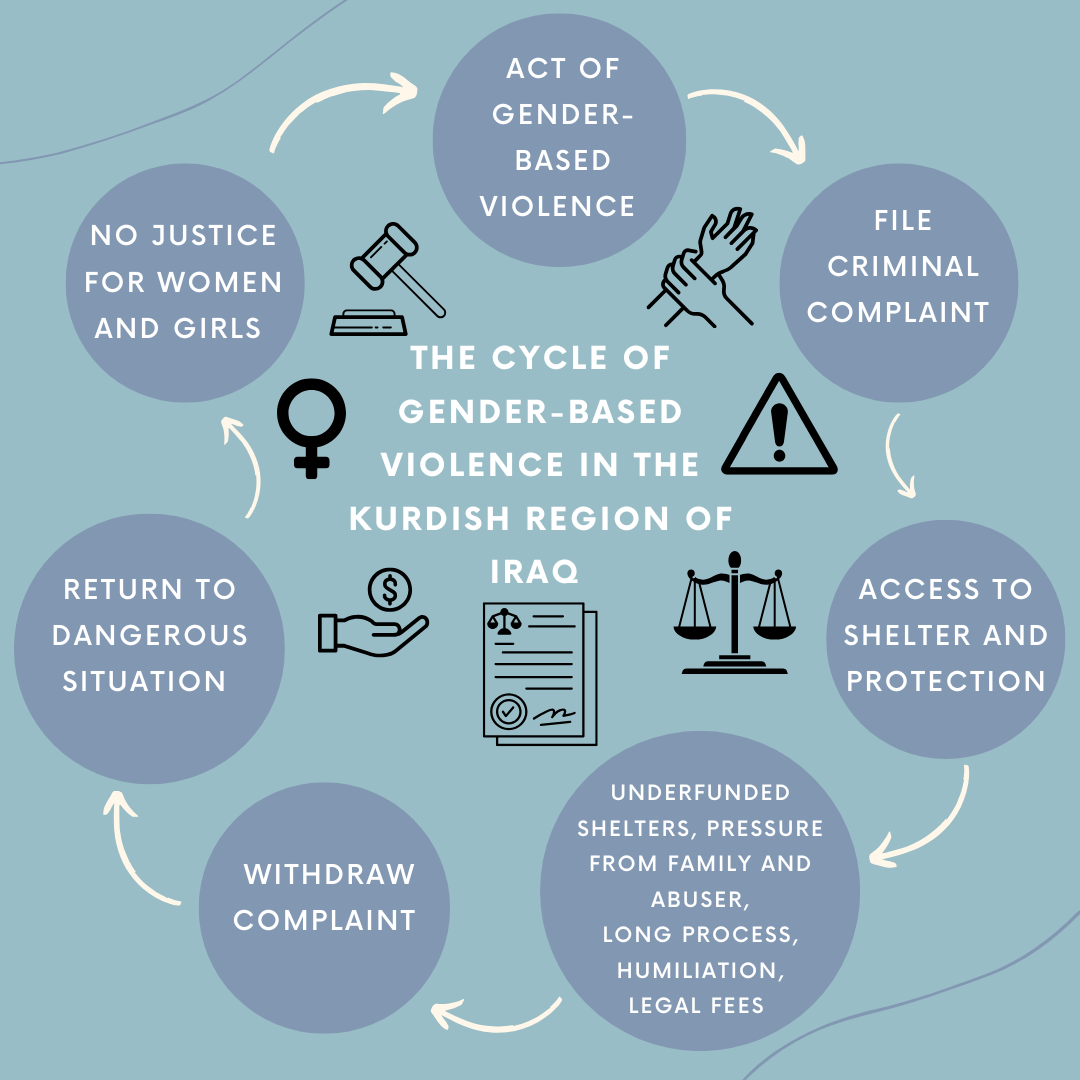

Barriers still prevent survivors from accessing the help they need. For example, survivors must file a criminal complaint against their abuser in order to access protection and safety. Without doing this, they cannot enter shelters designed to protect them from abuse. This traps them in a vicious cycle where they can’t seek support and shelter without filing a complaint, but filing such a complaint often leads to complications. Survivors might face increased threats and manipulation from their abusers and pressure from their families to withdraw their claims. Even after filing a complaint and entering these shelters, survivors encounter limited freedom and often face overcrowded, underfunded, and understaffed conditions (Amnesty International, 2024b). Male relatives can demand that a woman is to be released from the shelter and into their ‘care,’ which further puts survivors at risk. As a result, survivors of gender-based violence, particularly domestic violence, often find themselves back in the harmful situations they initially escaped (Bindel, 2021).

The KR-I established the Directorate for Combating Violence against Women (DCVAW) to address gender-based violence and help support survivors. However, the entity struggles to fulfil its duty due to underfunding. It cannot provide women with legal funding or aid once they file a criminal complaint, forcing them to bear the financial burden themselves, which many cannot afford. Many survivors end up dropping their criminal complaint due to pressures and threats from their family members and abuser. Not only this, but the judicial process is slow, and victims often face humiliation during trials, with judges prioritising family reunification over justice for survivors (Amnesty International, 2024a). These factors disincentivise women and girls from making a criminal complaint against their abuser, which limits their access to the necessary shelter and protection. If a survivor was to drop her case, the only safeguarding measure in place to protect her safety is that the abuser must sign a ‘pledge of no harm.’ However, this pledge is not legally binding, and many women and girls are murdered despite it. In September 2020, two sisters, aged 17 and 19, were found dead after dropping charges against their father due to pressure from their family. They had left the shelter only a month earlier (Amnesty International, 2024b).

While the KR-I has taken important steps to address gender-based violence through legislative reforms, it still remains a prevalent issue. Although these changes are promising, they have yet to create meaningful protection and justice for survivors. As Iraq paves its way forward in the aftermath of conflict, the country’s leaders must be willing to implement these reforms and dismantle the structures that allow gender-based violence to continue. Without change, these judicial reforms remain simply words on a piece of paper.

Conclusion

Tiba al-Ali’s story, like many others, is not an isolated tragedy. It is a sober reflection of the harsh reality faced daily by countless Iraqi women who live in fear in their own homes. Gender-based violence in Iraq is linked to the broader instability and conflict that have plagued the region. Iraq’s leaders must act to overhaul the legal framework that fails to protect women and girls, allowing this epidemic of violence to continue. Action is needed to safeguard women and girls during the judicial process, including increased funding for survivor support services. Without comprehensive reforms, a generation of Iraqi women will continue to be forced to live in fear. Not only this, survivors deserve justice and safety, and the chance to rebuild their lives away from their abusers without the veil of shame thrown over them by their families.

Glimmers of hope have begun to emerge from the darkness. Lawmakers in the KR-I are taking crucial steps to repeal provisions within the Iraqi penal code, sending a clear message that gender-based violence will no longer be tolerated. Across the country, Iraqi women are rising up and demanding the justice and protection for women and girls that they have been denied for so long. With their courage, combined with judicial and social reforms, there is reason to believe that a more equitable, safer future is within reach.

Bibliography

Amnesty International. (2024a). Daunting and Dire: Impunity, Underfunded Institutions Undermine Protection of Women and Girls From Domestic Violence in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq - Amnesty International. [online] Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde14/8162/2024/en/ [Accessed 20 Oct. 2024].

Amnesty International. (2024b). Iraq: Kurdistan Region’s authorities failing survivors of domestic violence. [online] Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/07/iraq-kurdistan-regions-authorities-failing-survivors-of-domestic-violence/ [Accessed 20 Oct. 2024].

Bindel, J. (2021). ‘As if she had never existed’: The graveyards for murdered women. [online] www.aljazeera.com. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2021/3/8/as-if-she-had-never-existed-the-graveyards-for-murdered-women.

Iraq: Penal Code. No 111 of 1969 [online] Available at: https://www.refworld.org/legal/legislation/natlegbod/1969/en/103522 [Accessed 16 Oct. 2024].

O’Reilly, G. (2023). The Iraqi YouTube star killed by her father. BBC News. [online] 5 Sep. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-64533577.

Puttick , M. (2024). War waged in the home: Rethinking conflict and gender-based violence in Iraq - Iraq. [online] ReliefWeb. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/war-waged-home-rethinking-conflict-and-gender-based-violence-iraq.

Rfaat, A. (2021). Violence against women and girls, a scourge affecting several generations. [online] www.unicef.org. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/iraq/stories/violence-against-women-and-girls-scourge-affecting-several-generations.

United Nations (2018). Impunity for domestic violence, ‘honour killings’ cannot continue – UN official. [online] UN News. Available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2010/03/331422.

In this episode Abigail discusses the epidemic of gender based violence in post conflict Iraq. She is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Department of War Studies, King’s College, London. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.