As Syria stands on a point of change, what is the fate of families living in ISIS refugee camps?

The final ISIS stronghold of Baghuz Fawqani fell in March 2019, marking the end of its seven-year rule over Syria. With the defeat of ISIS, the women and children, assumed to be affiliated with the group, were held in camps across northeast Syria and Iraq. The largest of the Syrian refugee camps is al-Hol, whose population reached 70,000 in March 2019, overwhelming camp authorities and placing huge strain on humanitarian supplies.

Globally, these refugees represent a real problem. On the one hand, foreign governments don’t want to import extremism, but these people, as individuals, have human rights as well. The balancing of these two needs is often left for NGOs to deal with. In reality, however, it is a global problem, and governments can’t just wash their hands of these individuals.

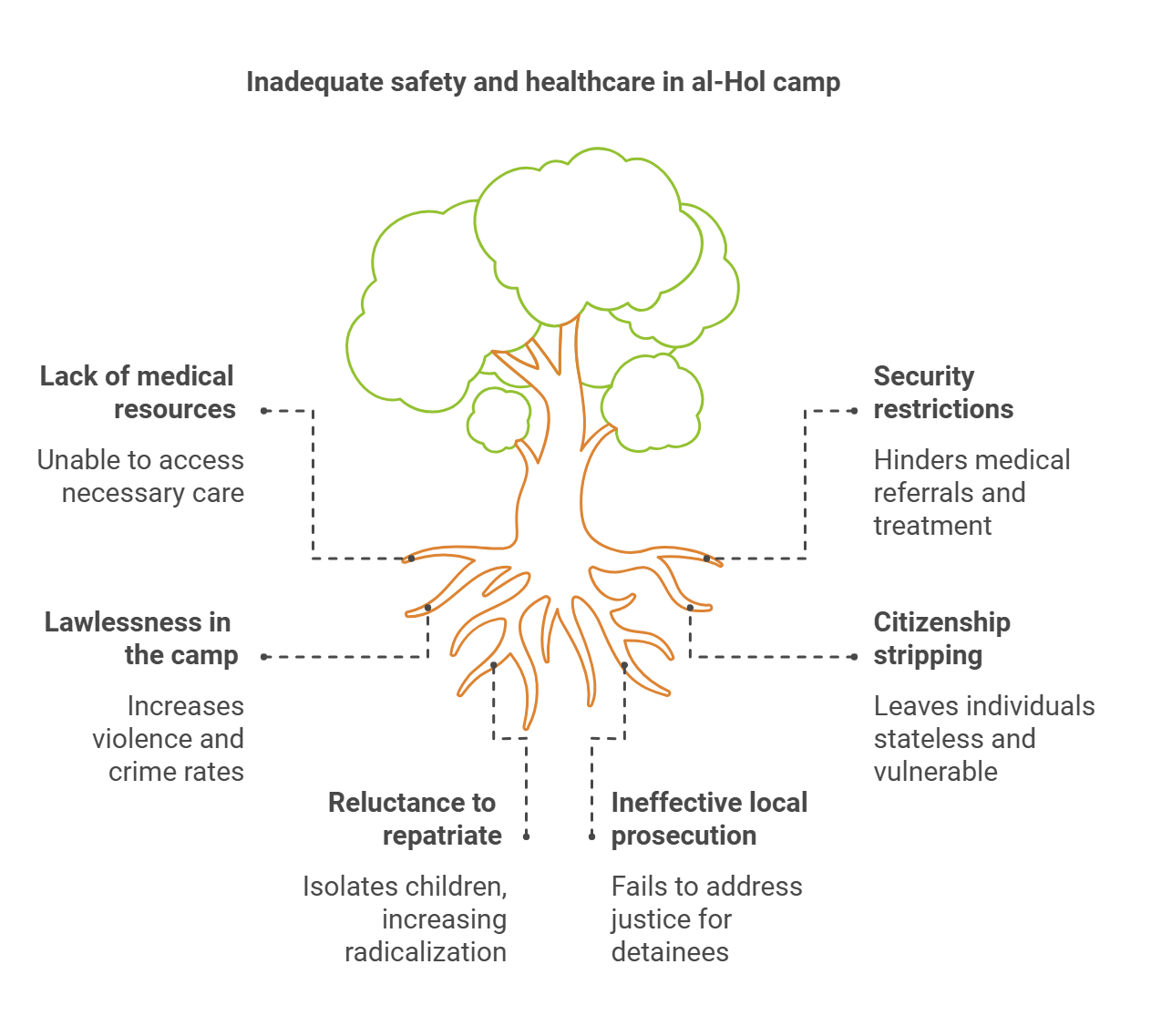

Their right to security is at risk as many at al-Hol camp are unable to access necessary medical care. This is due to a lack of specialist medical care within the camp and northeast Syria’s weak healthcare system.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) runs several clinics within al-Hol camp but often struggles to get approval for patients requiring specialist care from outside of the camp. In 2021, MSF referred 381 patients, including 63 children, for secondary and specialist healthcare.

However, many of those referred did not receive medical treatment. MSF reports that, in 2021, a total of 286 medical referrals to external health facilities were rejected by authorities, of which 205 were due to “security reasons.”

Medical facilities are particularly limited in the annex, a heavily guarded section of al-Hol camp housing 11,000 foreign women and children, mostly from North Africa and Europe. Unlike the main camp, the annex is without a fixed clinic. Instead, it relies on one static clinic and three mobile clinics run by MSF.

However, the mobile clinics are regularly interrupted due to security incidents, and to reach the static clinic patients must pass a checkpoint where they are registered and subjected to body searches and photographs. Furthermore, there is no access to health services in the annex after 1pm.

The limited services available in the annex mirrors their position globally. Some are viewed as subscribing to radical ideologies, with many having willingly left their home countries to join ISIS. Therefore, there is little drive internationally to help these refugees. The lack of medical care in the annex is just the tip of the iceberg, many have been abandoned by their respective countries who have refused repatriation and even stripped them of their citizenships.

Al-Hol’s conditions are further limited by a lack of any formal legal policies and practices in place to govern the camp. It has become increasingly lawless and suffers from extreme criminality, violence and insecurity. Residents are caught between the repressive measures of the security forces and the increasingly violent criminal groups.

MSF reported that in 2021 the leading cause of death in al-Hol camp was crime related, which accounted for 38% of all the deaths in the camp. In addition to this, 30 attempted murders were reported in the camp in the same year.

The causes of violence range from allegations of spying for the security forces, extortion of money by criminal groups, or to social control. It’s been reported that individuals affiliated with IS have been killed due to their lack of adherence to the camp’s cultural and religious norms.

Camp authorities have set up safe zones to house residents threatened by armed groups. However, the security of these safe zones is severely limited. On 12 November 2021, a group of armed men wearing uniforms entered the designated safe zone before shooting and killing two people and injuring several others.

The camp continually fails to fulfill residents’ needs for safety and security, breeding an atmosphere of lingering fear and constant apprehension. The need for safety and security is crucial for the residents of al-Hol who have endured years of war.

Foreign women and children are unable to leave al-Hol camp. Many governments have been reluctant to repatriate their citizens for the fear of importing extremism.

Although some governments have taken back their citizens, for example, Kazakhstan repatriated 156 of its children in October 2019. Yet the total number of children repatriated from the three main camps in northeast Syria is only 350. This is remarkably low considering 7,000 foreign children remain in these camps.

These children struggle to find connection and acceptance as they are refused repatriation by their home countries. This inability to connect to their home countries leaves them isolated and more susceptible to radicalization at the hands of those affiliated with IS and other criminal groups.

Some nations have resorted to stripping their nationals of their citizenship, ultimately leaving them without any form of protection or belonging. The British government has supported this method and since 2010,150 people have had their citizenship stripped.

This harms opportunities for international cooperation as other nations must take on the cost of detaining, housing, or prosecuting stateless individuals. This is particularly impactful on the administration of northeast Syria who is already dealing with the costs of reconstruction.

Citizenship stripping is seen as an ineffective method for fighting extremism as it leaves individuals without the possibility of rehabilitation. It also has serious implications on the individual as it deprives them of a much-needed identity and sense of importance.

Local prosecution, in Syria or Iraq, is seen as an alternative to repatriation. In theory, if people in these camps were successfully and fairly prosecuted, they would in turn be imprisoned or released from detention, and therefore there would be no need for the camps.

Many nations are attracted to local prosecution because local authorities have better access to witnesses and evidence, and it allows the country to avoid the costs associated with prosecution at home.

Concerns have been raised about the judicial process in Iraq and Syria. For example, Iraqi law convicts a person for joining ISIS not because of the defendant’s actions. In 2019, the French government received criticism when four French nationals were sentenced to death in a hasty trial in Iraq. Activists said the Iraqi courts often relied on circumstantial evidence and confessions made under duress.

The chance for foreign nationals to clear their names through local prosecution may not be available to the women and children of al-Hol camp. Syrian prisons are already filled with male militants who may have to face trial. It is likely these male prisoners would take priority over the women and children. Furthermore, the Kurdish administration in Syria has said they will not prosecute these women and children.

As the Kurdish administration struggles to provide adequate support and protection for the camp, this lack of engagement from foreign governments is concerning. While many governments are against repatriation, an alternative could be to help fund the detainment of their respective nationals. Actions such as this may help alleviate the strain placed upon the Kurdish administration as they attempt to rebuild their territory.

Today the issue of al-Hol camp is more pressing than ever. The question on everyone’s lips is, how is the international community going to help rebuild Syria now the Assad regime has fallen. Part of this is how we deal with the people in refugee camps such as al-Hol. Left unchecked, the camps in northeast Syria could become future breeding grounds for radicalization and undermine the sense of liberty taking hold of Syria today.

In this episode Sorley discusses Syria and the issues of families in the refugee camps there. He is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Oxford University Career Services. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.