Bridging the Divide: Public Art’s Role in Northern Ireland’s Reconciliation Journey

The Northern Irish Conflict:

From the beginning of the 1960s to the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, Northern Ireland experienced The Troubles, one of the bloodiest, most divided periods of the region’s history. The divisions fought over in the conflict were longstanding socioeconomic and political issues dating back to the 17th century which ultimately exploded between predominantly Protestant Loyalist communities and predominantly Catholic Nationalist communities. Throughout the conflict, public art was used as a form of expressing political allegiances in certain areas, marking territory and honouring martyrdom or political sacrifice. This was most visible in the many murals which emerged across Northern Ireland, as well as the increase in propaganda posters. After the conflict, public art was used as a tool for reconciliation between the opposing sides as artists strove to find connections and similarities between communities through their work. The question that remains is how successful can public pieces of artwork really be in rebuilding post-conflict communities and healing intergenerational traumas? What progress has there really been in public art in Northern Ireland since 1998?

The history of public art in Northern Ireland

Historically, public art within Northern Ireland has often been political. Loyalist areas have a longstanding history of murals, particularly those demonstrating a desire for maintained union with Britain, rather than Irish independence. As such, public art often depicted Loyalist symbols such as William of Orange or The Battle of the Boyne, a significant Protestant victory over Catholic King James II. The murals would often be repainted in time for Protestant celebrations on 12th July.

Image depicting a William of Orange mural retrieved from https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/how-murals-illustrate-northern-irelands-political-landscape

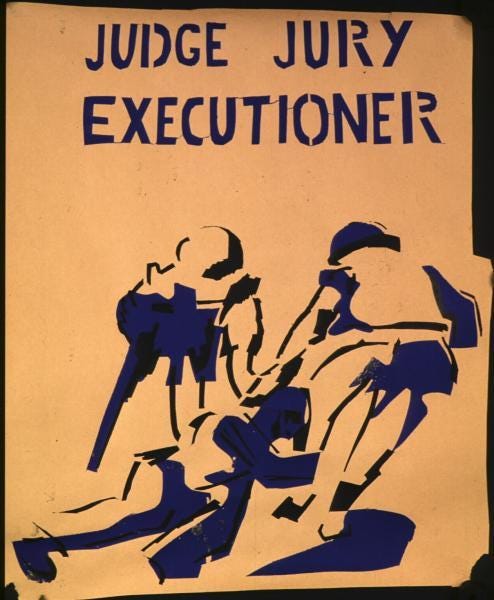

However, during The Troubles, murals began to appear in Catholic, Nationalist areas of Northern Ireland as well, beginning with murals which commemorated hunger strikers and steadily becoming more political. Public art then stretched to encompass propaganda posters which emerged particularly on the Republican and Nationalist sides. These were unflinchingly political and militant, using artistic expression to condemn government policies such as internment and the armed violence of Bloody Sunday as well as to increase suspicion of the ‘enemy’. This can be seen in the image below which portrays two British army soldiers dragging a civilian body under the words “JUDGE JURY EXECUTIONER”, condemning violence by the military towards civilians.

Image retrieved on 17/12/24 from https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/images/posters/ira/index.html

These types of posters became a common expression of public art, however, as the conflict drew to a close, there was a shift as art began to be used as a mechanism for reconciliation and peace.

Below, we will examine several public artworks within Northern Ireland to explore the power of art as a connecting force in divided post-conflict communities.

From protests to peace

Image of ‘Hands across the divide’ retrieved from https://theramblingwombat.com/2017/05/03/hands-across-the-divide/

‘Hands across the divide’ (1992), having been installed in one of the last few years of the conflict, is one of the first indicators of this shift in artistic expression to focus on reconciliation and is a powerful example of public art as a tool for collective healing post-conflict. The position of the sculpture above the Craigavon Bridge is of utmost importance as, during The Troubles, this bridge came to signify the division within Northern Ireland, with Catholics generally living on the city side of the bridge and Protestants on the Waterside.

The artwork functioned as a physical representation of a shared desire for peace and reconciliation at this time. Notably, the figures hands do not quite reach each other, powerfully demonstrating how this peace and unity had not yet been achieved but the effort to do so was in motion, visible in the physical exertion of both figures reaching across to bridge the gap. Whilst militant public art did continue to be produced, following this installation in Derry/Londonderry, it began to have a more peaceful focus, particularly after the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998 which marked the ‘official’ end of the conflict.

An example of such peace-focused artwork is the Millenium Sculpture in Strabane, more commonly known as ‘The Tinnies’ (2000).

Image of ‘The Tinnies’ retrieved from https://garethwray.com/product/millennium-sculpture-tinneys-strabane/

Strabane (which was an IRA stronghold during The Troubles and witnessed numerous bombings and violence from both sides of the conflict) is situated on the border between the North and the Republic of Ireland, meaning that the conflict was especially politicised in the area. ‘The Tinnies’ were constructed just two years after the Good Friday Agreement as part of a cross-border scheme to physically represent a ‘new and shared beginning for the community’. The figures are joyful, portraying three musicians and two dancers, and have a strikingly different tone to art made during the conflict. Far from presenting violence or division, the focus is on the unifying crafts of music and dance. As such, ‘The Tinnies’ are an example of how public art was used to embody a shared, hopeful entrance into the new millennium, in which there was an effort to leave division behind.

In 2007, the message of hope within public art became all the more explicit as the ‘Beacon of hope’ emerged on Belfast’s skyline.

#

Image of the ‘Beacon of hope’ retrieved from https://www.dreamstime.com/editorial-stock-photo-beacon-hope-sculpture-belfast-northern-ireland-uk-september-steal-statue-thanksgiving-square-called-also-nuala-image80287798

On the globe which the figure stands on, one can find the names of the many cities which the residents of Belfast have migrated to throughout history, presenting Belfast as part of a much broader geographical space than was felt during the insular period of The Troubles. As such, the piece presents a future for Belfast which faces out towards the world proudly, evident in the figure confidently reaching forwards. Likewise, the symbol of the circle which the figure holds reflects the idea of everything being linked together, implying a projection of community and unity through this figure. This is a stark contrast to the art of The Troubles, especially when juxtaposed with the propaganda posters examined above which purposefully highlight differences rather than connections.

As Northern Ireland then entered a new decade, there was an influx of public art which signified a new era of peace. The most obvious example of this is the Peace Bridge which was built in 2011 and bridges the physical and political gap across the River Foyle.

Image of the Peace Bridge retrieved from https://www.apm.org.uk/about-us/50-projects/technology/the-peace-bridge-londonderry/

Inspired by ‘Hands across the divide’, the bridge has two arms which reach in the direction of one another, forming a ‘structural handshake’ at the centre and thus manages to both physically and metaphorically connect the two communities from either side of the bridge. Visible from any point along the river, this artwork is as public as it could possibly get and was used in over a million crossings within just over a year of opening.

2011 also saw the construction of Belfast’s RISE sculpture and Derry/Londonderry’s Mute Meadow. Contrasting in approach, the spherical structure of RISE symbolises a “new sun rising to celebrate a new chapter in the history of Belfast”, firmly situating the focus on the future, whereas Mute Meadow looks back to the past. Found on former British army barracks, the piece is inescapably infused with the history of its location and yet its ambiguous meaning allows for interpretation by viewers and thus encourages progression, escaping the fate of becoming prescriptive or illustrative. In this manner, the artwork, whilst giving a nod to the past, empowers the city to move forward and write their own future.

More recently, the region has also seen a development in the mural tradition with an influx of murals with less politicised artistic subjects. Although sometimes these new murals do have a political focus, they are less often about the conflict of The Troubles. This is evident in the mural entitled ‘Love Wins’ which was highly political when it was painted in 2016 as it formed part of the same sex marriage campaign, a deeply controversial debate at the time.

Image of ‘Love wins’ retrieved from https://www.itv.com/news/utv/2016-08-01/love-wins-mural-unveiled-for-belfast-pride

As such, murals have become part of political and social campaigns, with one being created in 2017 as part of the campaign over suicide awareness and Belfast’s International Wall being transformed into the Palestinian Wall in response to the current situation in Gaza. However, there has also been a shift towards murals honouring cultural achievements within the region. One such example is the iconic ‘Derry Girls’ mural which celebrates the success of the TV show of the same name. Likewise, you could mention the ‘An Irish Goodbye’ mural which commemorates the Oscar-winning success of a Northern Irish short film, or the mural commemorating the punk band The Undertones – the list simply goes on.

Image of the Amelia Earhart mural in Derry/Londonderry retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cj7d80dgj05o

A further development that public art has seen in recent times is the appearance of a number of historical murals which do look to the past, but a past beyond The Troubles, emphasising that this is not all the region has to offer – it had a rich cultural past before The Troubles, just as it has a rich cultural present. Above you can see the iconic mural celebrating Amelia Earhart’s landing in Derry/Londonderry in her successful mission to be the first female pilot to cross the Atlantic but Northern Ireland is also host to murals commemorating its connection to the linen industry, the surprise arrival of a killer whale in the Foyle in 1977 and many other historic events. Whilst murals referencing The Troubles continue to be painted, these are often less intense and militaristic than in the past, such as this mural of women preparing food for the Ulster Freedom Fighters:

Image of a UFF mural retrieved from https://sharedfuture.news/street-art/

All of these artworks form part of a broader regional campaign and desire to rebrand Northern Ireland’s image, moving away from the all-consuming nature of the region's troubled past. Through public art installations, street art festivals, and murals celebrating cultural achievements, there is a concerted effort to shift the narrative and encourage pride in the citizens of Northern Ireland regarding their native land. Tracking the history of public art in the region post-conflict, there is a clear trajectory towards public art that focuses on shared cultural identity, social progress, and a hopeful vision for the future, rather than entrenching old divisions. However, the work of reconciliation is ongoing, and public art will likely continue to play a key role in Northern Ireland's journey towards lasting peace.

Bibliography

Barber, Fionna (2014) At Vision's Edge: post-conflict memory and art practice in Northern Ireland. In: Memory Ireland, volume 3: The Famine and the Troubles. Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, NY. ISBN 978-0-8156-5264-9

Gareth Wray Photography. (2024). Millennium Sculpture - Tinnie’s - Strabane | Irish Landscape Photographer. [online] Available at: https://garethwray.com/product/millennium-sculpture-tinneys-strabane/ [Accessed 20 Dec. 2024].

Imperial War Museums. (n.d.). How murals illustrate Northern Irelands political landscape. [online] Available at: https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/how-murals-illustrate-northern-irelands-political-landscape.

Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE). (2024). Peace Bridge: A Symbol of Unity Across Borders. [online] Available at: https://www.ice.org.uk/what-is-civil-engineering/infrastructure-projects/peace-bridge [Accessed 20 Dec. 2024].

Milliken, M. and Smith, A. (2022). The Post Conflict Generation in Northern Ireland: Citizenship education, Political Literacy and the Question of Sovereignty. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 17(3), p.174619792211145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/17461979221114551.

Orozco Diaz, B. (2016). Shared Future News — Branding peace: Public art in ‘post-conflict’ Northern Ireland #ESRCfestival. [online] Shared Future News. Available at: https://sharedfuture.news/branding-peace-public-art-in-post-conflict-northern-ireland-esrcfestival/ [Accessed 20 Dec. 2024].

Ulster.ac.uk. (2024). CAIN: Murals: Rolston, Bill. Contemporary Murals in Northern Ireland. [online] Available at: https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/bibdbs/murals/rolston.htm#murals [Accessed 20 Dec. 2024].

In this episode Rachael discusses the Northern Irish experience of using Public Art to build their national identity. She is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Oxford University Career Services. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.