Beyond the Ceasefire: Colombia’s Journey Towards Lasting Peace

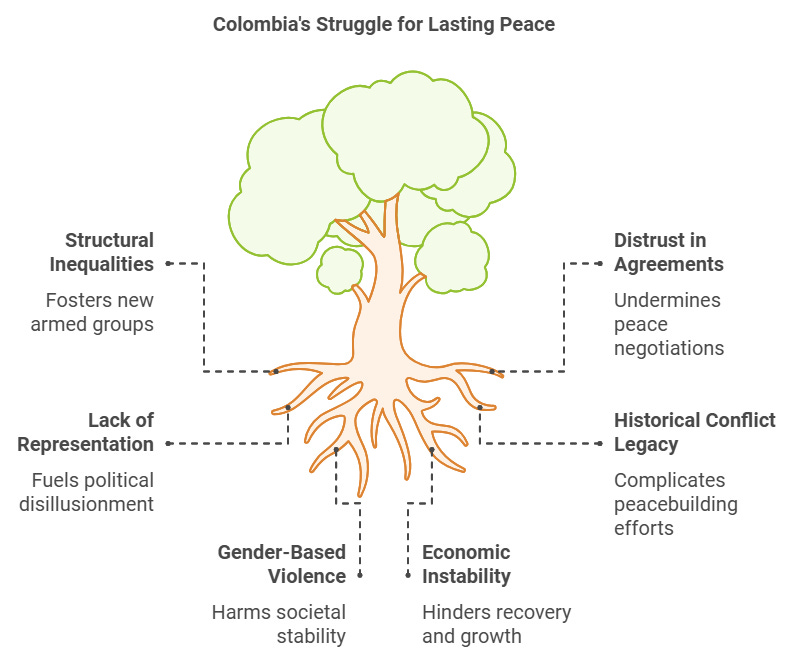

By exploring the landscape of Colombia eight years after the landmark 2016 Peace Agreement, this article hopes to explore complex interplay of human rights violations, economic instability and cultural shifts that have characterised the country’s journey to peacebuilding. In particular, I will emphasise how Colombia still grapples with structural inequalities that remain largely unaddressed, allowing new armed groups to fill the power vaccum left by the FARC. The persistence of gender-based violence against women and LGBTQ+ similarly highlight the harmful legacy of conflict on Colombian society.

Historical overview

Colombia has been beset by wars and the legacy of conflict since the country’s creation in 1819. To understand the nature of peacebuilding, it’s important to be aware that Colombia holds the distinction of being the Latin American country with the highest number of armed conflicts. In this environment where peace is often fleeting, peace agreements have proved temporary and have often been to no avail.

In the 19th century, for example, conflicts between regional elites most frequently ended in informal ‘gentlemen's agreements.’ These agreements allowed the militarily weaker side to maintain a degree of political authority, albeit in a subordinate role to victors. This tradition of informal peace practices within Colombia’s diplomatic processes has complicated the formalisation of lasting peace agreements for two main reasons: firstly, by creating a cycle of distrust towards formal agreements and secondly, failing to address structural inequalities.

These weaknesses have influenced the outcome of more recent history and can partly explain the 52-year conflict between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), which emerged in the wake of La Violencia. The end of this period of bloody Civil War between the Liberal and Conservative factions of Colombian society inspired the creation of guerilla groups in the 1960s. The formal power-sharing agreement which ended this period of war left the socially and economically marginalised groups in Colombian society excluded.

Lack of representation once again emphasised politicial inequalities and contributed to popular disullusionment. This sentiment mobilised left-wing guerilla groups to organise against the state and challenge the legitimacy of formal peacebuilding efforts. This enviornment havve rise to the FARCC, a peasant-veteran group affilitaed with Colombia’s Communist Party.

The FARC’s creation in 1964 marked a significant escalation in conflict. Primarily focused in rural areas crucial to their revolutionary struggle against land inequality, they took up arms against the newly unified government. Since the 1990s, the FARC’s involvement in drug trafficking activities and high-profile civilian attacks has led to their recognition as a terrorist organization by the UN, the US, and the Colombian government.

Widely recognised as the longest running domestic conflict in the Western Hemisphere, the violent confrontation between the FARC and Colombian government resulted in the death of over 200,000 people and displaced around 5.7 million more. It is within this context of prolonged conflict that peacebuilding efforts in Colombia should be understood. While the nuances of peacebuilding can significantly differ from those in other countries, particularly in Europe where formal treaties have been established, Colombia broadly recognises the function of peacebuilding strategies as relying on the direct containment of violence. The 2016 Peace Treaty reflected this with the call for an immediate ceasefire and government pledges to address systemic inequalities intended to provide a lasting resolution to domestic conflict.

What is the Peace Agreement?

On the 24th of November 2016, the Colombian government and the FARC signed a Peace Agreement which concluded over 50 years of conflict through a bilateral ceasefire.

Pioneered by President Juan Mauel Santos, the agreement centered on four key principles: the incorporation of the FARC into Colombian politics (by granting them five seats in Congress for the next two terms), the re-integration of former FARC insurgents into civilian life, the disarmament of the FARC, creation of Special Jurisdiction for Peace (to address criimes committed during the armed conflict).

Initially, this peace deal was set to be ratified through a public referendum that took place in October 2016. However, public disapproval with the conditions of the agreement, particularly regarding the creation of the FARC as a political party and possibility of reduced sentences for FARC perpetrators who collaborated in uncovering the truth about crimes committed during the conflict, led to its rejection by 50.2% of the population. Rather than conducting a second referendum, Santos made minor amendments to the agreement and subsequently ratified it through Congress, a decision that raised public scepticism and put the legitimacy of his government into question.

Despite this, the immediate impact of the agreement proved successful. In 2017, with the help of the UN, the Colombian government oversaw the disarmament of all FARC registered arms and the reintegration of 7000 former insurgents into civilian life. By aligning with the peacebuilding goal of eliminating direct violence, the Colombia government proved effective in appeasing the FARC and removing the most significant source of violence in the country.

The agreement also initiated significant political inclusion that paved the way for the election of the first left-wing president, Gustavo Petro, in August 2022. Petro was primarily elected for his pledge to implement ‘Paz Total’ between 2022 and 2026, an updated version of the 2016 Peace Agreement which aims to extend the ceasefire to other insurgent groups.

Within his first few months in power, the president passed the Law 418 of Paz Total which offered an opportunity for negotiations between the ELN and EMC, the two largest remaining guerilla groups, and the Colombian government to address sources of the ongoing domestic conflict. The dialogue based approach of Gustavo Petro’s government has, for the first time, reflected a government effort to address structural violence in Colombia. Cooperation with armed groups, such as the ELN, has led to an end to violent practices like hostage-taking and represent a peaceful effort to represent previously marginalised voices.

The investment of over $2 billion COP in December 2021 for the Colombia in Peace Fund (supporting victims of the conflict) is a step towards rebuilding communities affected by years of violence. Investment in social programs and the inclusion of civil society in internal peace discussions are key strengths of public opinion toward Petro’s administration. Importantly, they highlight the government efforts to understanding the root causes of conflict and seek to legitimise its approach to successfully transforming a post-war society.

These shifts in inclusion and funding are crucial in promoting social reconciliation between the government, insurgent groups and civilians and ensures that peace efforts are durable and representative for all Colombians.

What is still be done?

Despite the best efforts of the government, the possibility of peace remains elusive for many sections of Colombian society. As noted by Amnesty International, Colombia is still to date the ‘most dangerous country in the world’ when it comes human rights and individual protection. Efforts to address structural inequalities within society fall short of expected international norms. The ongoing culture of violence that exists within Colombian society can be seen through the widespread occurrence of gender-based and sexuality-based violence. The reported killing of 21 LGBTI people in 2023 motivated by ‘violence due to prejudice’ and negative perceptions of sexuality raises significant doubts about the potential for genuine social cohesion and unity in Colombia’s post-war society. The disparity between the enactment of the Gender Parity bill, passed in 2023, and the government’s declaration of a national state of emergency regarding gender-based violence the same year highlights a disturbing reality: sexual violence, rooted in the country’s normalisation of violence and power imbalances, may persist long after the formal end of the conflict.

Above all, the hardest struggle for the Colombian government to overcome is the socioeconomic conditions that reproduce armed conflict and structural violence. Though recent efforts of the Gustavo government with Paz Total has encouraged an updated ceasefire linked to social transformation, funding in social programs aimed at alleviating poverty and addressing wealth disparities in the country remains insufficient.

The close relationship between poverty and the radicalisation of marginalised guerilla groups has yet to be effectively addressed. Between 1964 and 2016, the FARC’s control over large parts of rural Colombia and their recruitment of insurgents in these regions was driven by financial inequality. While the Colombia in Peace Fund has indicated government investments in rural development, the rise of the ELN and EMC in recent years suggests security conditions in these areas have yet to improve.

Looking towards the future

The 2016 Peace Agreement marked the end of over 50 years of conflict that claimed the lives of thousands of people. The bilateral ceasefire was a historically signficant moment in Colombia, with the complete disarment of the FARC allowing a return to peaceful society. For the first time in history, the Colombian people were able to elect a left-wing President Gustavo Petro, who promised a revised ‘Paz Total’ peace agreementt aimed at fostering inclusive dialgoque and addressing the root causes of violence in the country. While the socioeconomic conditions causing the radicalisation of guerilla groups have yet to be fully addressed, Pedro’s open negotiations the ELN and EMC represent a critical step toward broadening peace efforts. Violent attacks on the LBGTQ+ community and the government’s declaration of a national state of emergency regarding gender-based violence reflect the challenges that contiue to be faced in translating progressive legislation into effective protection for marginalised communities.

In this episode Lola discusses the Post Conflict experience of Columbia 8 years after the peace deal. She is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Department of War Studies, King’s College, London. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.