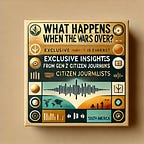

A Landscape Still at War: Cambodia’s Ongoing Battle with Landmines

Cambodia’s long peace is still haunted by weapons buried just beneath its feet. Three decades after the return of the monarchy and the birth of multi-party democracy, remnants of war are still very much present in the beautiful landscape of a country with a brutal history. Landmines contaminate the landscape, shaping the country’s physical and psychological terrain.

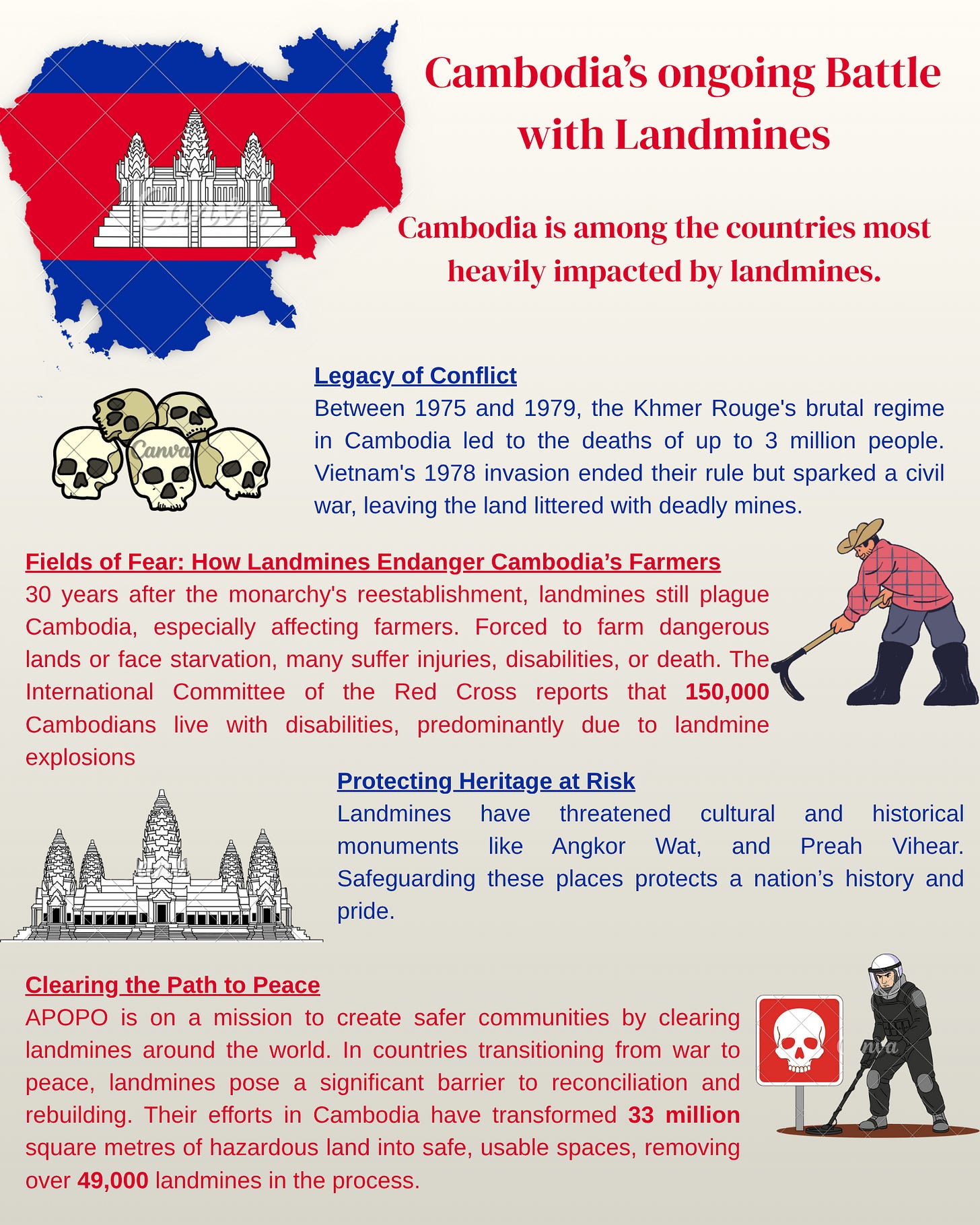

The northwest region, especially along the Thai border, remains a hotspot (Taskdal, 2011). It was here that some of the heaviest fighting unfolded. By 1995, Cambodia earned the grim distinction of having “a mine for every man, woman, and child” (Feingold, 1995). Many of these devices were planted indiscriminately across farmlands, forcing farmers to choose between feeding their families and risking their lives. The consequences ripple outward with reduced agricultural output, stunted economic growth, and communities trapped in cycles of fear and poverty. Even Cambodia’s cultural treasures weren’t spared. Angkor Wat, a UNESCO World Heritage site, was once surrounded by hidden explosives that deterred visitors and complicated preservation efforts.

Angkor Wat, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, 2025

Their danger lies in their simplicity. Most landmines rest just five centimetres below the surface. A few kilograms of downward pressure - far less than the weight of a child - can activate a spring-loaded firing mechanism. This mechanism strikes the detonator, triggering the explosive core. The resulting blast unleashes a brutal upward wave of force, causing devastating injuries in an instant (McGrath, p. 33, 2000). Planting a landmine costs as little as three dollars. Finding and destroying that same device can cost between $500 to $1000 hundred dollars (Feingold, 1995).

Legacy of Conflict: How Decades of War Buried Cambodia in Landmines

Cambodia’s recent history is scarred by extraordinary violence. Between 1975 and 1979, the Khmer Rouge pursued a fanatical vision of a “pure” agrarian society, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 1.5 to 3 million people, nearly a quarter of the population (Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 2025).

The regime’s collapse came only after Vietnam invaded in 1978, toppling the Khmer Rouge and installing a new government. But instead of ending the suffering, the intervention triggered years of civil war. As battles shifted across provinces, both Khmer Rouge fighters and Vietnamese forces planted the land with mines - crude, plentiful, and lethal (Feingold, 1995).

Furthermore, dangerous explosives were also left behind from the Vietnam War. Many of these mines, deployed by U.S. forces, remained undetonated in Cambodia’s soil (Taskdal, p. 189, 2011).

What remained after decades of conflict was the natural landscape turned into a weapon. Its rural fields and temples were littered with the remnants of war that would continue to claim lives long after the fighting had ceased.

Fields of Fear: How Landmines Endanger Cambodia’s Farmers

Cambodia remains one of the most heavily landmine-contaminated countries in the world. Unlike some post-conflict regions where danger zones are cordoned off with barbed wire or warning signs, Cambodia’s minefields are often invisible. In 2006, a staggering 90% of victims reported that there was no signage to indicate the presence of explosives (Taskdal, p. 189, 2011).

The people who suffer most are the farmers who rely on the land for survival. Faced with the impossible choice between farming contaminated soil or facing starvation, many continue to work fields riddled with hidden mines. The consequences are devastating. Injuries caused by landmines often result in death or life-changing disabilities. The International Committee of the Red Cross estimates that around 150,000 Cambodians live with disabilities, many of them having lost limbs to explosions (ICRC, 2018).

And even after amputation and medical treatment, the danger doesn’t end. As researcher Taksdal notes, “the disabled survivor or the family members will have to enter the mined area again and again, as they depend on farming, collecting wood or using other natural resources to sustain the family” (Taksdal, p. 189, 2011). Sok, a Cambodian farmer interviewed by Taskdal, lost a limb after stepping on a landmine, still remembers the moment that changed his life: “The accident happened three years ago, I was out in the jungle on my plot of land clearing the bush. I was not working for anyone else; I was trying to expand the farmland” (Taskdal, p. 191, 2011).

Clearing the Path to Peace: APOPO’s Mission to Reclaim Cambodia’s Land

APOPO, an international NGO, is dedicated to clearing landmines and returning safe, usable land to communities worldwide. Its work is rooted in a simple mission: restoring lives by restoring land. As McGrath notes, “countries in transition from war to peace may find that landmines laid by all combatant forces present a very real obstacle to reconciliation” (McGrath, p. 46, 2000). APOPO confronts that obstacle head-on, helping countries like Cambodia rebuild by making once-dangerous grounds safe again. So far, its work in Cambodia has cleared 33 million square metres of land and safely destroyed more than 49,000 landmines (APOPO, 2025).

To do this, APOPO relies on an unexpected ally: the giant African pouched rat. Native to Tanzania, these animals are trained to detect the chemical compounds found in explosives. Each time a rat correctly identifies a landmine, it is rewarded with food. When it locates an explosive, the rat scratches the ground to alert the deminers. Crucially, because the rats weigh so little, they can safely walk over active mines without triggering them (AFP, 2022).

APOPO Centre in Siem Reap, 2025

After visiting the centre in July 2025, it was immediately clear that the team holds deep respect and affection for their ‘mini rat heroes.’ Staff members proudly introduced us to several veteran rats, treating them with the same care given to any decorated service animal. Their contributions have not gone unnoticed. In the past, APOPO’s rats have received international recognition - including Magawa, now deceased, who was awarded the animal equivalent of Britain’s highest civilian honour for bravery for his extraordinary work in detecting landmines (AFP, 2022).

Myself at APOPO Centre in Siem Reap, 2025

APOPO’s impact extends beyond farmland. The organisation has also been working in Preah Vihear, the ancient Hindu temple complex designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site. By clearing landmines from the surrounding grounds, APOPO is not only protecting local communities but also helping to safeguard and restore one of Cambodia’s most significant cultural treasures (Mena Report, 2024). The work at Preah Vihear also speaks to a deeper national need: after decades marked by genocide and cultural devastation, restoring and protecting heritage sites is a vital step in rebuilding Cambodia’s identity and reclaiming what violence sought to erase.

Looking towards the future

Cambodia’s struggle against landmines is far from a relic of the past - it is a daily battle for safety, dignity, and the right to live without fear. From farmers risking their lives to feed their families, to heritage sites still recovering from the scars of conflict, the legacy of war is etched into the country’s soil. Yet amid the devastations, organisations like APOPO offer a path forward. Their innovative work not only clears deadly explosives but restores livelihoods, protects culture, and rekindles hope in communities long held hostage by hidden weapons.

But Cambodia still has a long way to go. As of November 2025, the disputed border territory between Thailand and Cambodia near Preah Vihear remains a source of tension - despite a 1962 ruling by the International Court of Justice, which signified it belonged to Cambodia. Thailand threatened to suspend a US-brokered ceasefire after a landmine explosion along the border injured four Thai soldiers - an incident Cambodia claimed involved mines left over from earlier conflicts (The Associated Press, 2025). This episode underscores just how long-lasting and geopolitically dangerous the landmines challenge remains.

Bibliography

AFP International Text Wire in English, Cambodia’s landmine-sniffing rat hero dies. 11 Jan 2022, <Cambodia’s landmine-sniffing rat hero dies - ProQuest> [accessed 12 November 2025]

APOPO, ‘APOPO in Cambodia’, 2025, <APOPO In Cambodia • APOPO> [accessed 12 November 2025]

Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, ‘Cambodia’, University of Minnesota, 2025 <Cambodia | Holocaust and Genocide Studies | College of Liberal Arts> [accessed 12 November 2025]

David A. Feingold, Silent Sentinels, Coward’s War, 1995, <Silent Sentinels, Coward’s War - Alexander Street, a ProQuest Company> [accessed 12 November 25]

International Committee of the Red Cross, ‘Cambodia: So little, yet so much for people with disabilities’ 5th June 2018 <Cambodia: So little, yet so much for people with disabilities | International Committee of the Red Cross> [accessed 12 November 2025]

MENA Report, Cambodia: APOPO extends collaboration for landmine clearance in cambodia with CMAC. (2024, Jan 02). <Cambodia : APOPO Extends Collaboration for Landmine Clearance in Cambodia with CMAC - ProQuest> [accessed 12 November 2025]

In this episode Beth discusses the post conflict experience in Cambodia and the issue of land mines left behind. She is a Citizen journalist with us on a placement organised with Department of War Studies, KCL. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post.