How the movie “Hiroshima mon amour” redefined the art of storytelling after a traumatic experience

“You saw nothing in Hiroshima”: The impossibility of representing trauma

Hiroshima mon Amour opens with a powerful scene: a man tells a woman that her effort to learn about what happened in Hiroshima is vain, and he keeps repeating “Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima, rien” (translation: “You saw nothing in Hiroshima, nothing”). The woman emphasizes her personal journey to learn about the event, visit museums, and watch historical documentaries. Both bodies appear as mutilated by the experience of love and the experience of Hiroshima, where destructive events are paralleled with an impossible love story. This questions how to effectively narrate the aftermath of a war horror, and how documents that might seem effective and complete are in fact impersonal and could never provide an effective insight about what happened and how people recovered from the trauma. Those experiences are impossible to represent accurately through a documentary, but rather remembering them through human experience such as love and death becomes a path to understanding those historical events.

Trauma is universal: personal and national experiences mirror each other

Initially, Alain Resnais, the director, was asked to make a movie about the atomic bomb. But he did not want to document or recreate the horror created by the atomic bomb, instead wanting to make a fiction movie that could be understood by a Western audience that did not experience the horror that signified the end of the war, a moment of relief. Thus, he juxtaposed two traumatic experiences: a woman’s experience in Nevers after German occupation, where she had her head shaved, and the man’s experience after the Hiroshima bomb. He shows the universality of trauma that is not grounded in one country but is rather universal, as every human being might experience it. In the movie, one line is “C’est comme si le désastre d’une femme tondue à Nevers et le désastre d’Hiroshima se répondaient exactement” (“It is as if the disaster of a shaved woman in Nevers and the disaster of Hiroshima answered each other exactly”), showing that both tragedies appear the same.

Another powerful scene shows the universality of trauma from a personal to a national dimension, where each protagonist says to the other “Hiroshima. C’est ton nom” (“Hiroshima is your name”) and “Ton nom à toi est Nevers” (“Your name is Nevers”). This scene overemphasizes how their experiences as persons reflect a broader psychological experience in a specific place. They are depersonalized, losing their individual identities and instead becoming experiences grounded in a specific time and period. It also shows how one traumatic experience mirrors another, and accessing trauma comes indirectly: we access the man’s traumatic past about Hiroshima through the woman’s experience of Nevers. Traumatic experiences can only be accessed through substitutions and displacements; we can never relive the whole story.

Trauma disrupts time and memory: storytelling through fragmented narratives

The movie also questions the notion of time and how people live it during and after trauma. For the woman who fell in love with the enemy, a German, during the war, she can’t differentiate her present Japanese lover and her past German lover: every memory is mixed, their identities become blurry. This shows how trauma is remembered not through images or documentaries but through the characters’ inner voices. When history of trauma can only happen through listening to someone’s experience, the narrative becomes non-linear and blurry; it doesn’t transmit an understanding of horror but the horror itself through fragmented, tormented narratives that can’t reconstruct a specific event but show how they experienced it.

The movie contradicts traditional techniques of storytelling, going against the committed literature movement of 1950s France, which was directed by Sartre and focused on the obligation of literature to represent reality as much as possible with detailed descriptions and politically engaging messages. Indeed, the movie opposes a commemorative system that reduces trauma into manageable facts and images that erase the singularities of survivors’ experiences. The movie ultimately shows how museums of commemoration tend to create one narrative of trauma that does not include all experiences. The movie also goes beyond narrative memories that integrate specific events into existing mental schemes, where this process of narrativization oversimplifies all experiences, focuses on one perspective while relativizing others, and transforms the past into something that can be told.

Furthermore, compared with other forms of commemoration, traditional monuments raise multiple questions such as who has the right to be remembered, whether states should construct those monuments since they were active participants in wars, and how to properly represent the unprecedented scale of violence. Then, “counter-monuments” began to exist: they were more inclusive because they necessitated audience engagement, had multiple voices, did not represent a single meaning, and were more of a process reflecting an ongoing act of remembering, not fixed memory. They leave traces without claiming to represent the whole picture. Thus, Hiroshima mon amour acts like a counter-monument because it does not pretend to represent Hiroshima or Nevers, but rather reconstitutes a testimony or the sensations lived by someone who experienced it.

Cinematic techniques express the inexpressible nature of trauma

The strong use of flashbacks puts the spectator in the place and time of the scene, recreating the exact circumstances and putting us in an anxious atmosphere. They permit a subjective memory representation and describe events more accurately. It also uses blurry scenes and fragmented memories. The movie’s vocation is to show how trauma is characterized by its resistance to coherent narrative memory, as traumatic experiences are overwhelming, unordered memories that disrupt mental frameworks and demand a structure representing disorientation, exhaustion, and losing usual markers. The movie embodies traumatic experiences as it does not reflect a coherent narrative but an elliptical one that is hard to understand and follow. The spectator is lost as the person who experienced the trauma; the past becomes blurry. This is what Marguerite Duras wanted to reflect: the movie contains many uncertainties about where we are, when, and who the two main characters are. It mixes the story of the two lovers and actual documentary footage such as museum exhibits, to show the intersection between personal experience and history. When the woman is imprisoned during the German invasion, one scene is striking: as she is imprisoned in a cellar, we lose track of time, we see scratched walls and a close-up of her scratched hands, like we scratched our own hands. Immersive scenes also help to reflect and tell traumatic experiences better.

Healing and remembrance: forgetting as part of remembering

The movie, beyond storytelling about social trauma to remember, also entails forgetting suffering and shows the impossibility of translating nuclear devastation into images or dialogues that reveal historical truth. Resuming life after trauma might depend on museums of commemoration because of their limiting representation. Naming each other by the country they are from at the end of the movie also shows reconciliation with their own history by forgetting traumatic details, reliving other memories, and the need for post-conflict communities to move on from tragedy. The woman’s experience of not being able to forget her past also shows the difficulty of detaching from an indelible past and the necessity to forget to fully live in the present, which she does not succeed in doing in the movie. The film shows that through acknowledging forgetting the past, one can live without losing it. Writing about trauma needs to happen within a framework that remembers that forgetting is part of the creative work.

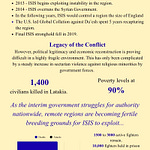

The movie also indirectly establishes itself within the cultural needs of post-conflict communities, reflecting the challenges of remembrance and cultural heritage. It shows how individual grief can be exchanged to enable collective international trauma, reflecting the need for cultural needs to be represented and heritage constructed. The film reflects on the difficulties of international memory and how to translate it between individual and collective memories, across national boundaries and cultural differences. One’s grief allows understanding someone else’s grief: the two protagonists did not live the same experience but did not succeed in telling the whole story of their trauma and still understood each other’s pain. The exchange of traumas creates equivalence but not equality: the woman loses her German lover, whereas Hiroshima killed many people. It is about exchanging traumatic experiences and recognizing that fully understanding the other’s experience is impossible.

Beyond its symbolic significance on Hiroshima, the movie delivers useful lessons for how we should narrate trauma today. With the abundance of photographs and videos in the modern world, information can easily be manipulated to create one narrative, which hinders individual experience in a conflict.

Bibliography:

Boyd Goldie, Matthew. “The Rhetoric of Grief: Hiroshima Mon Amour.” English Language Notes 46, no. 1 (2008): [page numbers not available].

Buendía Padreda, Sara. “Exploring the Interplay of Memory and Poetry in Rive Gauche Cinema: A Study of Muriel and Hiroshima Mon Amour.” Revista Foco 17, no. 3 (2024): 1‑11.

Holmqvist, Jytte. “Memory and Identity in the Emotive Map of Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959).” NANO: New American Notes Online 1, no. 6 (2014).

Just, Daniel. “The Poetics of Elusive History: Marguerite Duras, War Traumas, and the Dilemmas of Literary Representation.” Modern Language Review 107, no. 4 (2012): 1064‑1081.

Ledwina, Anna. “Une dialectique de la mémoire et de l’oubli : Hiroshima mon amour de Marguerite Duras.” Quêtes littéraires, no. 12 (2022): 73‑84. https://doi.org/10.31743/ql.14868.

McKee, Stephen. “The Memorial Film: Commemoration through Cinema in Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour.” [Publication details not fully available].

Mohsen, Caroline. “Place, Memory, and Subjectivity, in Marguerite Duras’ Hiroshima mon amour.” Romanic Review 89, no. 4 (Nov 1, 1998): 567.

Roth, Michael S. Hiroshima Mon Amour: You Must Remember This. (Yale University Press),

Varsava, Nina. “Processions of Trauma in Hiroshima mon amour: Towards an Ethics of Representation.” Studies in French Cinema 11, no. 2 (2011): 111‑123. https://doi.org/10.1386/sfc.11.2.111_1

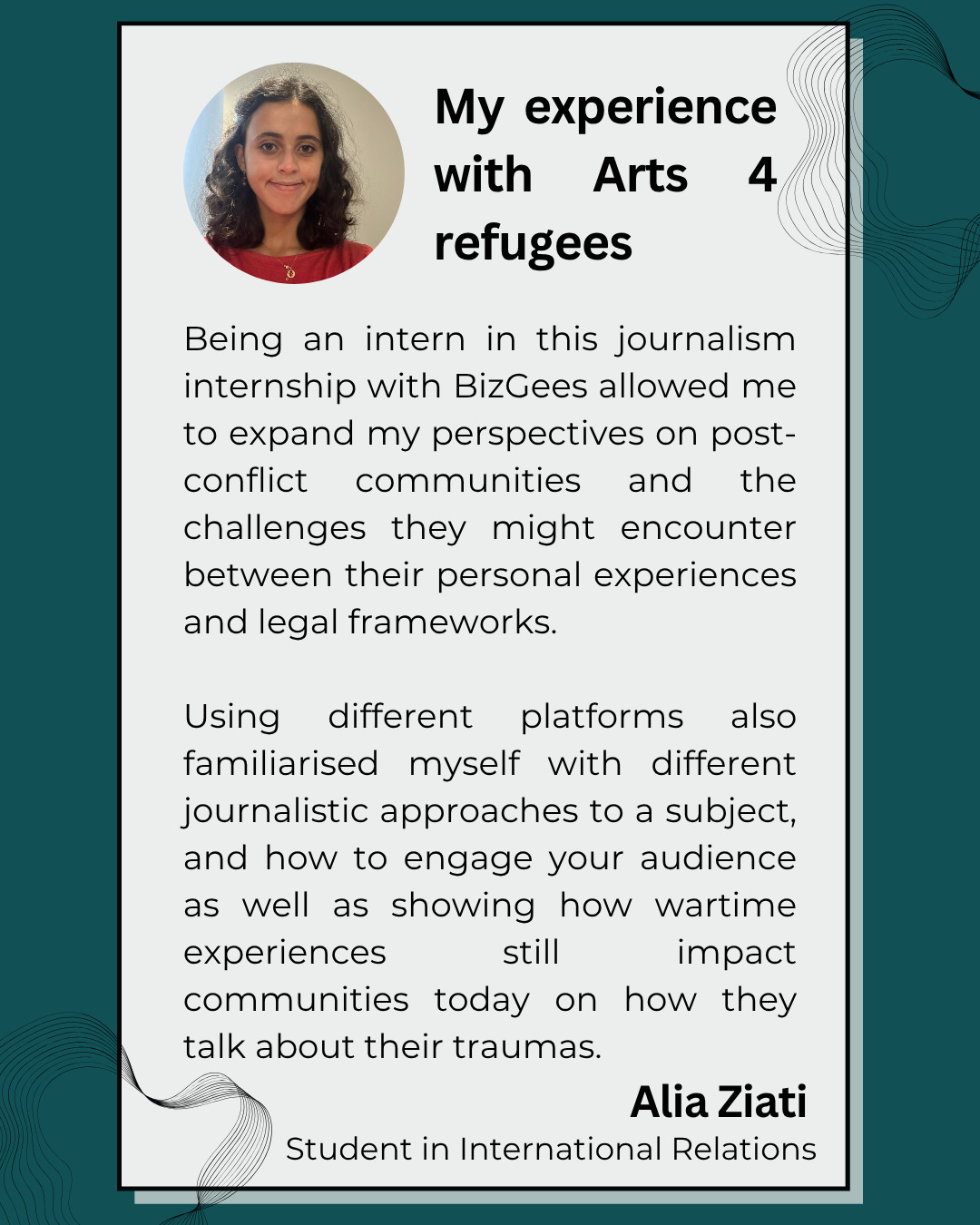

In this episode Alia discusses the complexity of healing and trauma in post conflict Japan. She is a Citizen journalist with us on a placement organised with Department of War Studies, KCL. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post.