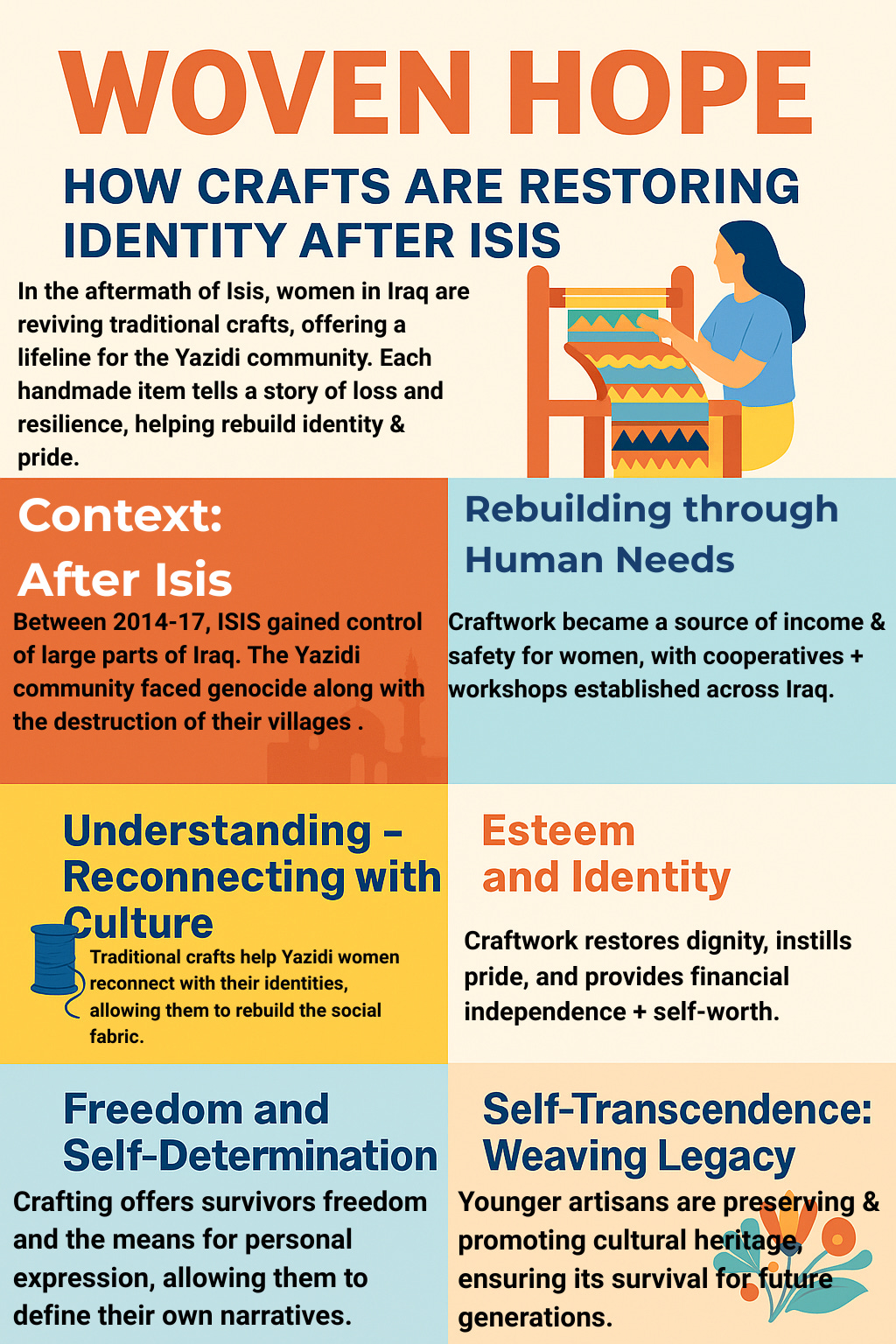

Woven Hope: How Crafts are Restoring Identity after ISIS

In the aftermath of ISIS, the rhythm of the loom filled the silence left by war. For the women of Iraq, each pattern woven became more than simple fabric, it highlighted liberation and quieter forms of rebuilding. In the towns of Mosul and Sinjar, women who once fled violence sat side by side, restoring the traditional crafts of their ancestors. For the Yazidi community, these crafts became the very lifeline which would restore identity, purpose, and pride. Each handmade item told a story of loss and resilience in a land steadily sitting itself back together. So, how is identity being rebuilt from ruins?

Context: After ISIS

Between 2014-17, the Islamic State seized large parts of northern Iraq, including Mosul and Sinjar. The Yazidi community, a religious minority within the region, faced genocide: thousands were either killed or enslaved; women and young girls taken captive; villages ransacked and destroyed; and cultural artefacts looted or burned.

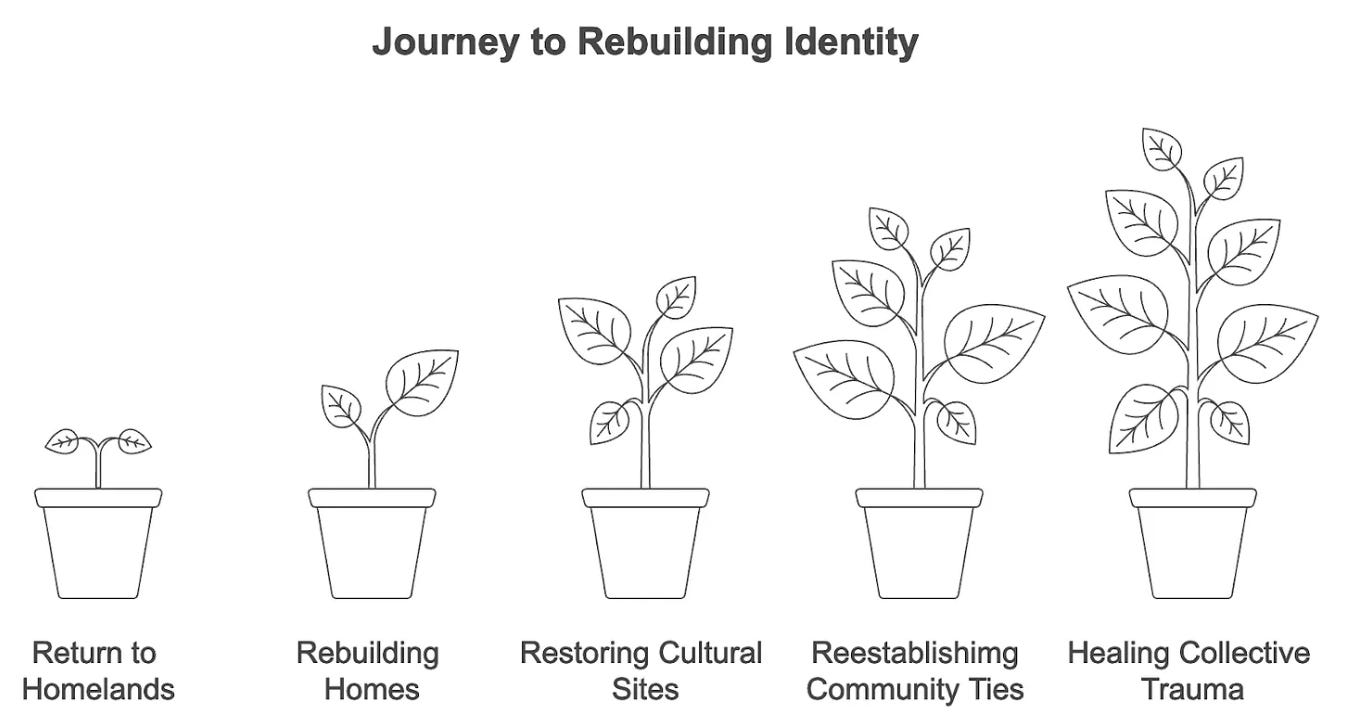

In the defeat of ISIS, survivors returned to a homeland physically and spiritually scarred. As such, communities rebuild from nothing - homes, livelihoods, and trust.

In a fragile land, traditional crafts were not only symbolic of heritage, but they represented a pathway to healing, security, and self-expression.

Rebuilding Through Human Needs

Survival, Security, and Safety

The first step was ensuring survival. After the destruction by ISIS, very little was left and craftwork quickly became a source of income and safety for women. Local NGOs and international partners established women’s cooperatives and sewing workshops across northern Iraq. Many participants were forcibly displaced or widowed during the time of ISIS, and so these spaces gave women the means to earn a livelihood, while remaining securely within their communities.

For Yazidi women, weaving and embroidery became more than a stream of income, it allowed them to reclaim agency in an environment where they had once found themselves hopeless. Kurti Khalaf Haso, aged 50, began tailoring business in 2016 with a simple sewing machine. In 2021, she was awarded over $2500 from the UNDP, along with business management training. Haso experienced significant personal losses during the rule of ISIS, and the opportunity to expand her business provided stability for her family (UNDP ‘Iraqis Rebuild’, 2024).

Wool is processed and spun by hand at the Khanke Carpet Factory. Sarah Ali/UN Migration Agency, 2018.

Understanding - Reconnecting with Culture

Beyond the fabric: crafts offered a bridge between the past and present. In Sinjar, older women taught the younger generations of symbols and stories woven into traditional textiles. The symbols of sacred peacocks, the sun, and the flame have become vessels of collective memory, once threatened by war. The revival of each motif reclaims a culture once targeted for erasure.

The revival of crafts is not just nostalgia, it is understanding. The use of traditional crafts allowed women to reconnect with their identities before the conflict, anchoring their selfhood in something enduring and distinctly Yazidi. Crafts rebuilt the social fabric that war had torn through - in acts of creation, communities rediscovered trust and the possibility of peace.

Contribution and Participation

As women found ways to contribute, the possibility of healing deepened. Elders began to train younger women in old designs and traditional techniques, while youth workshops encouraged creativity and ancestral motifs. Schools began to introduce craft sessions with an aim to ensure children could learn their heritage through practice.

Teaching and producing ensures survivors became active participants in the recovery of their culture and economy.

Yazidi women during vocational training. Sarah Ali/UN Migration Agency, 2018.

Esteem and Identity

Each finished piece strengthened pride for Yazidi women, with each item sold ensuring financial independence, and renewed self-worth. For many Yazidi women, these crafts represented visible and active survival - proof that after devastation and ruin, beauty could be crafted through their own hands.

One displaced woman from Sinjar, Mayasa Broo Rasho, stated: ‘“I never had the opportunity to attend school, not even to learn how to read and write… When I was accepted to work on craft and weaving products, I was determined to learn everything I could… (this work) helped me mentally.” (FreeYezidiFoundation, ‘Resilience through Crafts & Enterprise)

These creations became both income and affirmation for these women, restoring dignity where humiliation had once thrived.

Freedom and Self-Determination

Freedom concerns the power to choose, and for survivors, crafting offered them freedom which had once been stripped from them. Some women began to adapt traditional patterns into more modern forms and art and fashion, exporting their personal identity into each woven product.

Each act of creation became a form of resistance against the forces that once tried to erase them. Each artisan defined her own narrative and crafted independence, creativity, and control.

One Yazidi artisan, Flous, explained: “My mind can relax a little when I come to the factory and work.”, (IOM UN Migration, ‘Weaving A Brighter Future’).

Self-Transcendence: Weaving Legacy

The final thread in this story concerns legacy, as younger generations of artisans are now digitising traditional patterns and utilising social media to promote their work. Through digital storytelling, artisans ensure agency over their culture, while working against possibilities of future cultural erasure. These stories are not only remembered, but they are shared globally.

The efforts of Yazidi women represent the highest form of recovery, transcending trauma to preserve identity and culture for future generations. Memory is woven into examples of resilience.

Healing Trauma through Creation

The rule of ISIS left deep wounds - emotional, physical, and spiritual. After surviving captivity, forced displacement, and loss of families, silence replaced speech and pain became easier to carry alone.

In workshops across the north of Iraq, weaving and embroidery has become the language of healing. These small, deliberate acts of selecting colours and aligning patterns helped to restore a sense of control against deep wounds of trauma. For survivors, this control is crucial.

When women work side by side, trauma gives way to trust, and conversation replaces months of silence. This becomes a collective way of stating: we are still here, and our culture remains.

The Numbers Behind Recovery

Data from aid agencies offers a clearer picture of recovery, while thousands of Yazidis remain displaced, growing statistical evidence suggests craft and culture is helping them to heal:

In the United Nations Development Programme sewing workshops, a total of 280 women were trained across four cities, (IOM UN Migration, ‘Weaving A Brighter Future’).

In the same UNDP sewing programme: 480 school uniforms were produced by the trainee artisans, (IOM UN Migration, ‘Weaving A Brighter Future’).

In Khanke, 30 women organised an all-female team at a carpet factory, several were internally displaced and eight were breadwinners for their families, (IOM UN Migration, ‘Weaving A Brighter Future’).

In Anbar, the number of machines in a workshop grew from 10-24 to support displaced and vulnerable women. (IOM UN Migration, ‘Women Supporting Women: Sewing in Abu Ghraib’).

Dr. Hayat Ibrahim, a psychology professor at the University of Baghdad, established a workshop in the Abu Ghraib District to gather 20 women to produce uniform vests for schoolgirls - although not specifically concerning Yazidi women, this demonstrates the importance of crafting and practice in the face of sectarian conflict. (IOM UN Migration, ‘Women Supporting Women: Sewing in Abu Ghraib’).

Image of a rug crafted by female artisans in Khanke, listed on the FreeYezidiFoundation.

Global Threads of Hope

Across the world, creativity has become a powerful language for recovery. In Rwanda, genocide survivors weave Agaseke peace baskets, while some in Afghanistan embroider motifs once banned by extremists to reclaim their right to beauty and expression.

According to UNESCO, the global cultural and creative industries employ nearly 30 million people, generating over $2,250 billion annually (UNESCO, ‘New Report shows cultural and creative industries account for 29.5 million jobs worldwide’). As such, culture has been proven to be an engine of recovery and resilience.

So what?

So, what does this mean for Iraq, and for us?

For Iraq, every rug woven and every pattern revived is more than artistry, it is a declaration that culture survives conflict. For Yazidi women, they are not merely recovering from war, they are redefining what peace looks like through their own hands.

For the rest of us, it is a reminder that peacebuilding is not solely for politicians, it is in classrooms and workshops, where dignity is reclaimed thread by thread..

When communities rebuild through culture, they survive and teach the world how to heal.

Bibliography

FreeYezidi.org, (https://freeyezidi.org/free-yezidi-crafts-enterprise/)

FreeYezidi.org, (https://freeyezidi.org/voices-from-field/resilience-through-crafts-enterprise/#:~:text=“My%20name%20is%20Mayasa%20Broo,not%20cause%20harm%20to%20anyone.)

Iraq.iom.int, (https://iraq.iom.int/stories/weaving-brighter-future)

Iraq.iom.int, (https://iraq.iom.int/stories/women-supporting-women-sewing-abu-ghraib?)

In this episode Rabab discusses the post conflict experience post ISIS. She looks at how the arts and crafts are supporting the rebuilding of community and helping victims deals with mental health issues. She is a Citizen journalist with us on a placement organised with Department of War Studies, KCL. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post.