Struggles and Strengths: Tamil Women and Children in Post-War Sri Lanka 🇱🇰🙏

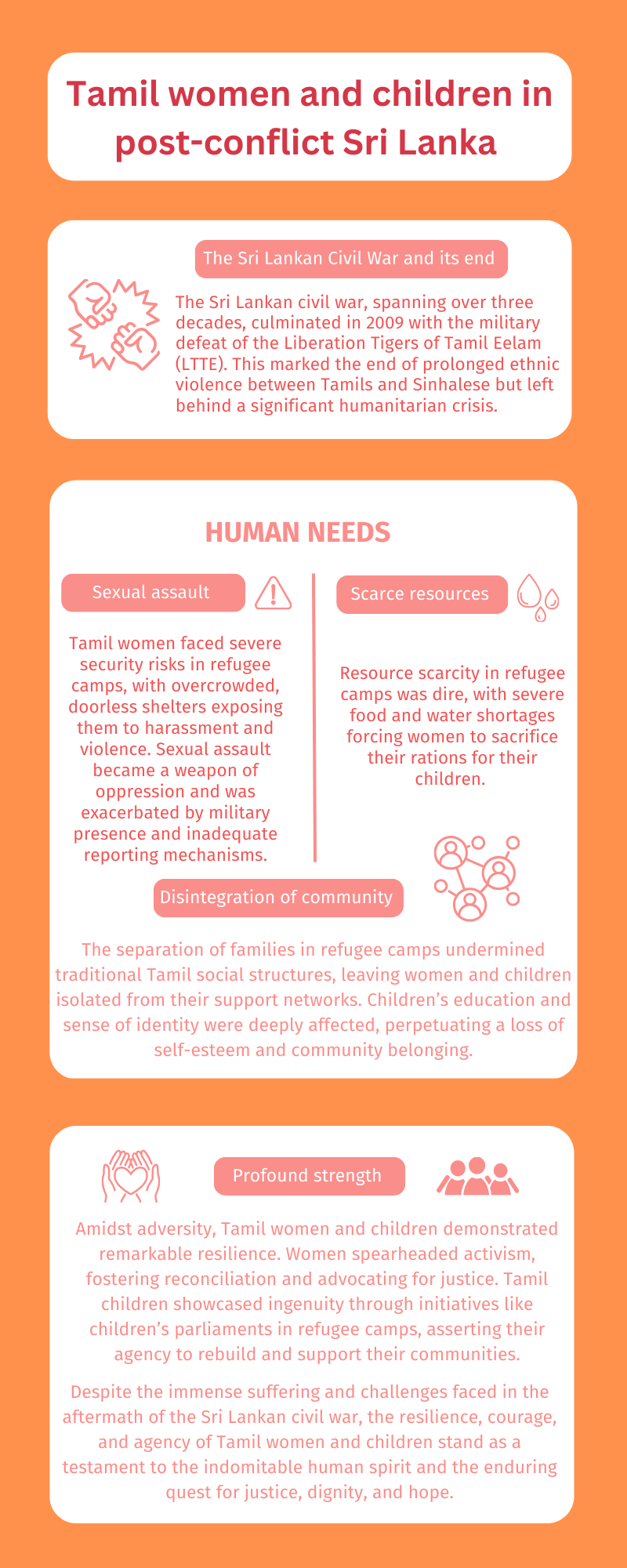

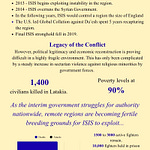

2009 marked the end of a three-decade-long civil war in Sri Lanka. Ethnic tensions between Tamils and Sinhalese had been simmering since Sri Lanka gained independence from British rule in 1948. Key flashpoints include the 1983 pogrom known as “Black July” and the long-standing insurgency led by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), both of which inflicted severe violence and unrest on Sri Lankan society. The defeat of the LTTE in May 2009 brought the war to a close, but it also triggered an immense humanitarian crisis.

Swathes of Internally Displaced Refugee Camps sprung up in the Northern Province districts such as Vavuniya and Kilinochchi, as well as in the Eastern Province in areas like Tiruchirappalli and Madurai. At the peak of displacement, nearly 300,000 Tamil civilians were housed in these camps, and by 2010, approximately 106,000 remained. High-security zones in military-occupied areas, extensive landmines, and destroyed infrastructure made it nearly impossible for many families to return home. Beyond Sri Lanka’s borders, over 100,000 Tamil refugees sought shelter in India, residing in camps managed by the Indian government. The treatment of these refugees became a politically charged issue, especially following the assassination of Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi by the LTTE, which led to harsher conditions and discriminatory treatment for the Sri Lankan refugees.

The difficulties faced by refugees in camps are vast and often too harrowing for words to adequately capture. The refugee experience is not homogeneous, and the trauma manifests in myriad ways. Women and children, in particular, often face unique and less visible forms of repression. Recognizing and understanding the realities faced by Tamil women and children is crucial for comprehending the reality of post-conflict Sri Lanka in its totality - realities of both struggle and strength.

The struggles of women and children

Temporary shelters were hastily erected in the refugee camps, causing structural vulnerabilities. The absence of doors left the approximately 89,000 female-headed households vulnerable to significant security risks, and several unrelated families were often in the same tent. Privacy was rare for women, and for simple acts of changing clothes, women would often leave the camps to neighbouring meadows with little light, increasing their vulnerability to sexual assault. The female body regularly became a site of violence, causing great grievance to the women and simultaneously attacking the Tamil communities' honour values and inner sanctum. Female autonomy over their own body was brutally stripped away in efforts to dehumanise Tamil communities. In the Tamil populated area of Mullaitivu, the disproportionately high rates of birth control, alongside the forced contraception in Kilinochchi, implies systematic discrimination, potentially as a tool of ethnic oppression. The strong military presence in these camps created a particularly hostile environment for women. Tamil women reported regular instances of being watched by soldiers while bathing, and older women reported soldiers expecting sexual favours in return for bringing food to their family. Despite the UNHCR establishing a desk in some camps for women to report abuses, the lingering military personnel near the desk scared many away from reporting such abuse. Such direct threats to the security and safety because of overcrowding and forced exposure was not exclusive to adult women. Refugee children were also extremely vulnerable to sexual and physical abuse. In the ‘warehouses’ in Indian refugee camps, coercive methods again reveal how female bodies were weaponised as instruments of state control. Interviews also describe instances of young girls being provided with cell phones, taken to lodges, or sent to garment factories - situations that often resulted in sexual abuse.

Resource scarcity was another grave challenge. Acute shortages of food and water plagued camps in Sri Lanka and India. NGOs rationed their resources and would prioritise nutritional supplement food for pregnant mothers and children under 5, leaving 70% of children in the largest camp in India between 6 and 15 malnourished. The heaviest burden of scarcity fell on women, who sacrificed their own rations for their children and spent hours queuing in the heat for additional supplies. Fetching water, an arduous task requiring long walks, exposed women to the risk of sexual assault. Further, the scarce access to resources and institutional support made them vulnerable to coerced sexual practices as they were limited in ways to provide for their family. To provide for one’s family was core to the cultural connection and acceptance of Tamil women.

The need to belong is a universal human need, just as physical safety and survival are. Embodying social structures, norms and values are what allow for this sense of belonging. The conditions and compositions of the refugee camps attack the very foundations of the infrastructure of the community. Tamil women particularly are historically understood as the bearers of culture, and their loss of agency in maintaining the home threatens their very value in society. As male and female refugees are often split up when entering a camp, it is rare that families are able to stay together. Women and children feel very remote from their extended family and support networks. Their sense of identity as a contributing member of a larger community is grossly undermined. The self-esteem of children in this context is also vulnerable as the stigma associated with being a refugee, and all the stereotyping and discrimination it entails, greatly affects their confidence. Without strong education support, this sense of self as an emerging member of the community is further damaged. Whilst post conflict recovery in education was a priority for UNICEF, significant challenges remained post war in terms of the quality of education and infrastructure. Many children were out of full-time education and thus estranged from a social practice that develops awareness of their role in society. Women and children alike suffered greatly under the post-conflict social and cultural disintegration.

The strength of women and children

The realities of Tamil women and children in refugee camps are inhumane and deeply disturbing. Yet such a narrative runs the risk of casting both women and children as passive victims of repression. Children especially are often treated as subjects who are unable to grasp the complex political realities. This is far from the truth. In fact, stories from across the camps reveal cases of admirable creativity and defiant exertions of agency amidst such brutal conditions. A particularly inspiring case comes from India, where there was a children’s parliament in every Sri Lankan refugee camp. The parliament is made up of a prime minister, a deputy prime minister and a minister for eight other sectors including health, education and communication. It was the minister’s duty to support the network of children across the camp, clearly nurturing the human need for contribution and participation. If a child cannot go to school due to inadequate school supplies, the minister of education would inform the minister of communication and alert the supporting NGO officers to solve the situation. Despite the repeated restraints on self-actualisation and self-determination from limited resources and inadequate infrastructure, Tamil children regularly used their agency. They established informal networks to address complex problems in the camps, supporting the growth of their community, and in turn, themselves.

Women’s efforts were fundamental to the post-conflict reconciliation process. Goodwill missions to north and east regions formed part of efforts to foster understanding between Tamil and Sri Lankan communities, with women offering free Tamil classes to bridge divides between ethnic groups. Despite few formal roles being available to Tamil women in shaping the transitional justice policies, they were key to agenda setting activism. At a time when independent research was prohibited, many women courageously shared their testimonies with NGOs, despite the constant threat of surveillance and harassment from the military and police. Their statements played a crucial role in shaping key UN reports and advocating for human rights at the UNHRC, underscoring that violations persisted even after the war’s conclusion and strengthening the call for an international investigation. Meanwhile, women activists on the ground took legal action and mobilised protests, demanding that authorities address issues such as disappearances, land grabs by the military, and sexual violence.

The human need to be understood, to connect and to contribute is palpable in these efforts. Despite enduring unimaginable suffering, assault and dehumanisation, many Tamil women and children continued to find ways to restore hope and worked to build their community from ruins into something once again recognisable.

In this episode Mercy discusses Sri Lanka and it’s post conflict concerns. She is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Oxford University Career Services. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post.