Religious Minorities In Ruins: The Legacy of Genocide and Shattered Identities Post-ISIS

As the guns fall silent and dust settles in regions liberated from ISIS, what kind of home are the Yazidis and Christians of Syria and Iraq returning to? After enduring ISIS's campaign of genocide and cultural erasure, these religious minority communities face the immense challenge of rebuilding not just their physical surroundings but piecing back together shattered identities. The scars left by the terrorist group's occupation run deep, etched into the cultural, spiritual and social fabric of these regions.

ISIS’s Reign: A Campaign of Genocide and Erasure

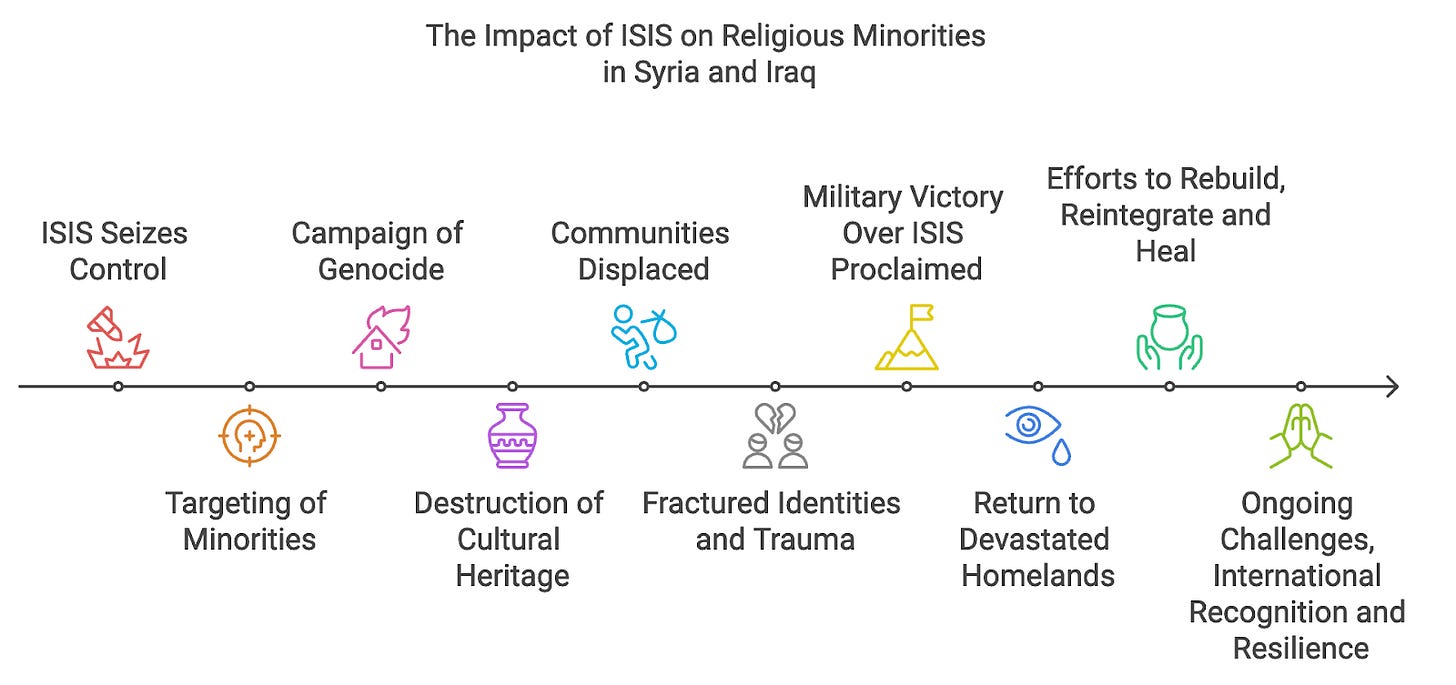

Between 2014 and 2017, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) seized control of vast territories across Syria and Iraq, exploiting the instability from the Syrian civil war and the collapse of Iraqi security forces. During this time, ISIS established a self-declared caliphate, enforcing a rigid and extremist interpretation of Islam in these regions. Within this context, ISIS issued numerous doctrinal and policy declarations, specifically targeting Yazidi, Christian, and other non-Sunni Muslim minorities for destruction. These declarations openly expressed ISIS's intent to commit genocidal acts against these communities. This campaign of terror was central to its broader goal of instilling fear and asserting control by eradicating or subjugating non-Sunni populations under their rule.

The genocide against the Yazidi minority by the faction marked an unprecedented level of horror. The Yazidis are an ancient community with a unique religion and beliefs. Most Yazidis are ethnically and linguistically considered Kurds and predominantly live in Northern Iraq. They were branded as ‘devil-worshipper pagans’ and shirk—idolaters—contrary to monotheism. The jihadists launched a ‘purification’ campaign against the complex and cosmopolitan mosaic of the Middle East. This campaign included mass killings, displacement, sexual enslavement, the rape of women, girls being forced into marriages, and boys turned into child soldiers for the regime. On August 10, 2014, many Yazidis were trapped on the besieged Mount Sinjar in Iraq, where they faced death from hunger and thirst. In total, it is estimated that between 10,000 and 12,000 Yazidis have been killed or abused.

ISIS also targeted Assyrian Christians, an ancient civilization of Mesopotamia. The Assyrian Christians faced forced conversions, executions, kidnappings, deployed as human shields, separating children from mothers and displacement from their ancestral homes. ISIS referred to them as ‘slaves of the Cross’. These acts are part of ISIS’s goal of religious homogeneity and the cleansing of these communities from the territory altogether. On October 2015, the extremist group released a recording of three Assyrian men getting executed.

On August 10, 2014, people from the Yazidi minority, fleeing violence from the Islamic State in Sinjar town, walk towards the Syrian border, on the outskirts of Sinjar mountain. Source : Rodi Said / Reuters.

Alongside their violence, ISIS systematically destroyed cultural landmarks, obliterating shrines, temples, churches, mausoleums, distinctive symbols, and homes. This deliberate iconoclasm aimed at eradicating Yazidi and Christian heritage, targeting both ancient and modern manifestations of their faith and customs. The goal was to undermine cultural and religious pluralism in the region. It was cultural genocide, designed to erase these groups from history, present time and space and weaken the cohesion of these minorities. While ISIS’s destruction of heritage is a common tactic, its attacks on sites belonging to these minorities were distinctive in their spread and ferocity. Unlike the well-mediatized destructions of ancient archaeological wonders like Palmyra, the erasure of Yazidi and Christian holy places received little attention in Western media.

A member of a militia associated with the Syrian Democratic Forces walks through the ruins of a church destroyed by Isis. Source : The Financial Times, 2019.

A Legacy of Layered Genocides

This cultural and human genocide was not an independent act. It was orchestrated to connect with earlier waves of discriminate killings endured by both communities. Throughout their history, Yazidis have endured repeated episodes of repression and violence, including Saddam Hussein’s Arabization policies in the 1970s and terrorist attacks, such as the 2007 bombings in Sinjar that killed 250 and wounded 350. Similarly, Christians have undergone significant persecution in the Middle East, echoing the Armenian genocide at the end of World War I.

ISIS's brutality presses into painful wounds. This layering of genocides makes the violence of the present evoke trauma of the past. For the Islamic State, these acts were justified by a holy mandate, claiming to succeed where previous persecutors had failed, barely distinguishing between both human 'enemies' and their material expressions of 'unbelief'.

Survivors carry the weight of not only having lost family members but also their place in a community that was once tightly knit. The mental health toll is significant, with many survivors struggling with feelings of alienation, loss of identity, and the emotional burden of having witnessed their cultural erasure.

Broken Homes and Heritage, Broken Identities

For those who survived, returning to their homeland is a painful process. With ISIS eventually defeated in key strongholds, minority communities have slowly begun to return to areas like Sinjar, Mosul, and Raqqa. However, Yazidis and Christians face a return with no possibility of 'normalcy.' The land they come back to is not only physically broken but also spiritually and culturally wounded. The destruction of sacred and distinctive spaces has made it difficult for these communities to reconnect with their traditions and religious practices, which are deeply tied to the land and the physical spaces ISIS sought to obliterate. The loss of these sites represents a loss of connection to each other, their past, and their sense of place, signaling the ontological death of their community and identity. Material heritage and symbols play a crucial role in shaping collective identity, serving as tangible manifestations of a community. Indeed, they are repositories of history, culture, and memory. The destruction of sites inflicts deep symbolic suffering, as material culture provides the foundation for a person or group's orientation in time and space. Without these anchors, communities lose the means to reaffirm their identity, leaving individuals stripped of their sense of self and belonging.

A Long Road to Healing

As they slowly return to their homelands, communities face the immense challenge of rebuilding not only their physical surroundings but also the very essence of who they are. While the physical remnants of ISIS’s destruction can eventually be repaired, the deeper wounds inflicted on these communities’ identities cannot be fixed with brick and mortar and will take generations to heal. Survivors grapple with the horrors they witnessed, while trying to rebuild their homes and sense of identity in a region that no longer feels like it. The loss of cultural heritage, the fragmentation of community ties, and the trauma of genocide have left Yazidi and Christian people in a precarious position, struggling to reclaim their social place and identity in a region transformed by war.

Displacement remains a central issue. Many Yazidis and Christians are either in camps within Syria or Iraq or as part of a growing diaspora across Europe and North America. The social cohesion that once defined these communities has been fractured, and families have been scattered across different countries. For those in exile, the connection to their ancestral homeland is fading. This fragmentation makes it harder for the community to come together and rebuild the cultural bonds that were so central to their identity.

The path to healing - both individually and collectively - will be long and fraught with difficulty. Yet, there remains hope for the future in their resilience and determination to reclaim their identity, even if a full return to ‘normal’ may never be possible.

Efforts in Rebuilding, Reconciliation and Reintegration: Homes, Faith and Society

Cultural and Religious Revival: The Yazidi community has worked diligently to restore their religious practices and traditions after the devastation caused by ISIS. A key part of this effort is the rebuilding of sacred sites like the Lalish Temple, which holds great significance for Yazidi identity. Alongside this, they are reclaiming rituals and holidays that ISIS sought to erase. Similarly, many Christian communities, especially in regions like the Nineveh Plains, have returned to destroyed churches and monasteries to restore them. For them, rebuilding goes beyond the physical structures, as it is also about reclaiming a sense of spiritual and collective identity.

Rebuilding Homes: Many survivors who have returned from captivity have found their villages in ruins. Communities have initiated grassroots efforts to clear the rubble and rebuild, often relying on diaspora support to fund such efforts. The reconstruction of entire villages and towns devastated by ISIS’s occupation presents a significant challenge. International aid, alongside local initiatives, is crucial for rebuilding homes, schools, and infrastructure. However, progress has been hindered by insufficient resources and ongoing security concerns.

Legal Recognition: At the same time, both Yazidis and Christians are striving for justice. They are pushing for the international recognition of the genocide committed against them and the prosecution of ISIS members. Some groups have also focused on securing land rights and legal protections to ensure that they are recognized as equal citizens in Iraq and Syria.

Social Reconciliation: A major challenge is restoring trust with neighboring communities, some of whom were seen as complicit during ISIS’s attacks. For Christians, tensions with local groups make reconciliation efforts essential for achieving long-term peace. On an individual level, women face significant challenges reintegrating into their society due to the trauma and stigma around sexual violence and many families have yet to be reunited, with many orphaned children.

Trauma Healing and Support: Additionally, psychological trauma remains a significant barrier to recovery, particularly for Yazidi women and children who were held captive by ISIS and abused. Specialized support in the form of counseling and rehabilitation is crucial. Organizations such as Yazda and the Free Yezidi Foundation provide mental health services and help with reintegration. Similarly, Christian groups have established community centers aimed at offering psychological and spiritual healing to those affected.

A Fragmented Future: Resilience Amidst Uncertainty

Despite the proclaimed military defeat of ISIS, the future remains deeply uncertain for Syria and Iraq's religious minorities. Ongoing violence, political instability, and local conflicts continue to jeopardize their prospects for return and recovery. In liberated areas, sporadic attacks by ISIS remnants and clashes between armed factions have left many Yazidis and Christians fearing for their safety. Those who do manage to return often face discrimination and hostility from other groups, struggling to reintegrate into communities that no longer feel like home.

Yet, amidst these overwhelming obstacles, glimmers of resilience and hope persist. International efforts have begun to assist with the restoration of key religious sites, and there is growing advocacy for justice and accountability. In 2017, the UN recognized the genocide committed by ISIS against Yazidi, Christian, and other non-Sunni minority groups. And on ratifying soil of the International Criminal Court, such as Germany, individual members party to the crimes committed have faced prosecution and punishment.

These steps, while limited, signal a recognition of the immense trauma and loss endured by these communities. As they slowly rebuild their physical and social fabric, the path forward remains fraught with uncertainty. But the determination of the Yazidis, Christians, and other minorities to reclaim their identity and rightful place in the region continues to inspire.

In this episode Carla discusses the epidemic of gender based violence in post conflict Iraq. She is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Department of War Studies, King’s College, London. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.