Life after the peace accord: the reality of Colombia’s indigenous and Afro-descendant communities

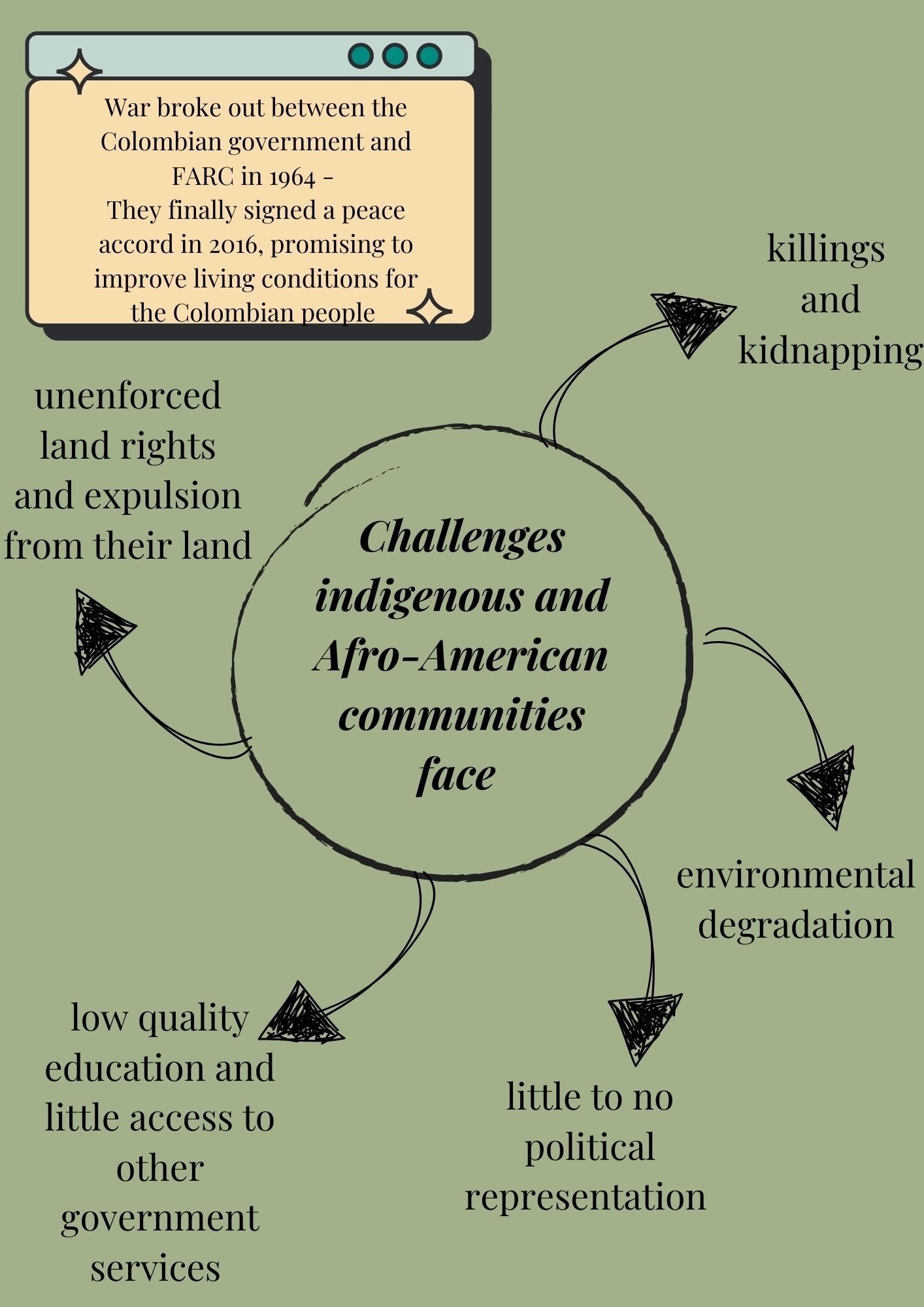

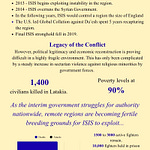

The war between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces (FARC), which is a marxist-lennist guerrilla group, broke out in 1964. The conflict lasted for more than five decades and came to an official end in 2016, when the two parties finally signed a peace accord. The peace treaty aimed to not only end the fighting but also restore stability and enhance living conditions of all Colobians across the country. However, its implementation so far has been slow and uneven, with rural areas benefiting little from government initiatives. As the state has not been able to effectively fill the power vacuum left behind by the war, FARC dissidents often step up to fill the gap. This is especially true for the Southern state of Nariño where FARC dissidents have increased their presence in and control over rural areas. However, it is mostly indigenous and Afro-descendant communities, who tend to live in these rural areas, which means these communities particularly struggle to fulfill their fundamental human needs with violence still ongoing.

This includes their need for security and stability, connection and belonging, autonomy and freedom, recognition and significance, growth and development, contribution and participation, and transcendence and meaning. In many indigenous territories, drug trafficking and illegal mining, mostly carried out by various rebel groups, have proliferated. This has left many of these communities vulnerable to territorial disputes, kidnapping, forced displacements and also killings. Especially communities along the Pacific coast have experienced increased violence as armed groups in these regions are fighting for control of strategic sectors for drug trafficking. Furthermore, illicit mining and deforestation on their land has had a devastating impact on the environment, causing river pollution, loss of biodiversity, and degradation of sacred sites. On top of that, economic and social development remains a major challenge for indigenous and Afro-descendant communities. The peace accord’s crop substitution program to diversify farming has been poorly implemented, leaving thousands of families without income. Moreover, infrastructure, healthcare and education in many rural areas, where indigenous and Afro-descendant communities tend to live, are inadequate. Despite local efforts to enhance these services, the overall picture shows that there are deep structural inequalities which continue to hinder economic growth and development in these regions.These conditions make it extremely difficult for indigenous and Afro-descendant communities to feel economically secure and physically safe in post-Conflict Colombia.

Furthermore, Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities continue to suffer a sense of displacement, disconnection, and marginalisation. Because of the continued violence, many families had to flee their lands. Although the peace accord included provisions for land restoration, these processes have been slow. This means that thousands of families are still unable to return to their home. However, indigenous identities are often very deeply tied to their ancestral land. Hence, being unable to return to their homes has meant that indigenous and Afro-descendant communities find it very hard to reestablish their traditional ways of life, often leaving them feeling disconnected from their identities. Additionally, the ethnic chapter of the peace accord aimed to protect indigenous and Afro-Colombian cultural rights. But its implementation has also been slower compared to other parts of the agreement.This is mostly because state-led initiatives to restore cultural identities are underfunded, uncoordinated or lack local participation. As a result, indigenous and Afro-descendant communities have struggled to reconnect to and preserve their traditions and culture. Many community leaders have highlighted the need to recognize traditional healing practices, oral histories and spiritual leadership but there has been little governmental support for these efforts. The feeling of disconnection of indigenous and Afro-descendant communities is likely to persist if the government does not increase its efforts to better protect and promote their way of life. This means that indigenous and Afro-descendant communities still struggle to fulfill their need for identity and significance.

Additionally, autonomy and self-governance remain a central concern for these communities.There have been attempts by indigenous and Afro-descendant people to enhance their control over their territories, and the goal of the peace accord was to build upon these ambitions for indigenous and Afro-colombian autonomous governance. However, once again, implementation has been slow. Indigenous leaders often encounter legal and bureaucratic obstacles when attempting to reclaim ancestral lands or manage local resources. Furthermore, extractive industries and agribusiness are still pushing into indigenous territories without their consent. And as government presence in these areas is weak, indigenous communities’ land and autonomy rights are often not enforced. This has resulted in inadequate protection of land and natural resources and greatly affects indigenous and Afro-descendant communities’ ability to fulfill their need for autonomy.

Indigenous and Afro-descendant people are often still unable to meet their need for participation and contribution. During the conflict, indigenous and Afro-descendant populations were often considered peripheral to national policy making processes. Although the peace accord brought their suffering into the forefront, the implementation of policies that were to promote the identity of indigenous and Afro-descendant people has been inconsistent. The peace accord intended to increase political participation for historically marginalized groups. However, indigenous and Afro-descendant leaders still have difficulties to fully engage in the policy-making process. The Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), the transitional justice system created by the accord, has been slow in addressing historic injustices. Indigenous leaders have called for greater participation in policy making structures for land, economic development and security. On a positive note, however, there has been an increase in the number of indigenous and Afro-descendant representatives at the local level, but in general, the system is difficult to navigate for communities that have traditionally not been represented in formal political structures. This has made it incredibly hard for these communities to be part of Colombia’s decision-making process and leading their needs and concerns to often fall off the agenda at the national level.

In conclusion, the indigenous and Afro-descendant communities of Colombia are still facing significant challenges in the post-peace accord period. Although large scale armed conflict has decreased, violence and insecurity still exist - particularly in regions which have been reclaimed by illegal armed groups. Displacement, lack of land restitution, and slow implementation of the ethnic chapter of the accord have hindered attempts at community reconstruction and enhancing of cultural identity. Efforts towards self-governance and autonomy are still ongoing, however, there are significant legal and economic barriers. Political participation and justice measures have improved but are still incomplete. Also, the conservation of indigenous and Afro-descendant cultural and spiritual traditions remains a challenge in a rapidly modernizing society. The implementation of the peace accord has been slow and uneven. This has greatly hindered the ability of these communities to meet their fundamental human needs fully, which prevents them from thriving. The situation shows that recovery from a conflict is a process that is not only lengthy but also one that is especially difficult for indigenous or other traditionally marginalized sections of society. It further highlights the ongoing need for governmental policies that directly address the specific challenges faced by these communities to ensure an even development across all of society.

References:

Colombia - changing conflict dynamics still disproportionately affect most vulnerable. IDMC - Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. (2024, May 14). https://www.internal-displacement.org/spotlights/colombia-changing-conflict-dynamics-still-disproportionately-affect-most-vulnerable/

Hassan, T. (n.d.). World Report 2023: Rights trends in Colombia. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/colombia

Human rights in Colombia. Amnesty International. (n.d.). https://www.amnesty.org/en/location/americas/south-america/colombia/report-colombia/

NRC. (2023, November 23). Colombia: Peace remains elusive for tens of thousands trapped by armed groups. NRC. https://www.nrc.no/news/2023/november/Colombia-peace-remains-elusive-for-tens-of-thousands-trapped-by-armed-groups

In this episode Sofie discusses Columbia and the issues local communities face after the peace deal with FARC. She is a Citizen Journalist with us on a placement organised with War Studies Department, King’s College, London. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.