The Kachin State in Myanmar: the Plague of Gender-Violence at the hands of the Tatmadaw

Countries in South-East Asia grapple with a long history of conflict and violence, Myanmar is not stranger to this. Since their independence in 1948, the country has struggled to develop due to a lack of comprehensive government action. Furthermore, the existence of minority ethnic groups across the country who fight for their autonomy has made unification even more difficult.

This article aims to look into gender-violence in the Northern Kachin State of Myanmar. It highlights the struggles of the Kachian people at the hands of the Myanmar Army, the Tatmadaw, investigating the pain inflicted by the Tatmadaw on the Kachin community and how legal mechanisms allow these crimes to go unpunished. Finally, it highlights how to address gender violence in this community.

The Struggle for Kachin Autonomy in Myanmar

Myanmar (then Burma) gained independence from British rule in 1948. However, the country struggled with ethnic conflicts, corruption, political instability, and economic challenges. In 1958, the democratically elected leading party handed power to the military to fix the situation, which was returned in 1960 (McKenna, 2024).

Yet, the central government in Myanmar neglected the Kachin State and its people. The Christian minority suffered religious suppression from the predominantly Buddhist government, which restricted religious practices and destroyed churches (McKenna, 2024). The state faced significant socio-economic challenges, including poverty, illiteracy, lack of education, and inadequate healthcare.

As a result, the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) was formed to advance the rights of the Kachin people. Their armed branch, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), engaged in conflict in 1961 with the Burmese Government's Army, the Tatmadaw. This conflict was characterized by guerrilla warfare against the Tatmadaw until the 1990s, when peace negotiations began.

Both parties recognized the need for economic development in resource-rich Kachin State. The government promised a framework for dialogue regarding the political autonomy and recognition of the Kachin Peoples, a priority for the KIO.

This led to a 1994 ceasefire, marking a temporary halt to fighting, which did not last. In the 2000s, the Tatmadaw began to build up their army in the Kachin region. The KIO perceived this as an attempt by the government to exert control over the region. Furthermore, in early 2011, negotiations over Kachin people's rights stalled. In June, the Tatmadaw launched an offensive against the KIA, breaking the ceasefire and leading to a devastating conflict (Hein, 2024).

The Prime Minister at the time, General Thein Sein, attempted to negotiate another ceasefire between the KIA and the Tatmadaw. Yet the Tatmadaw did not respect this authority and continued to attack even after a bilateral ceasefire agreement in 2013.

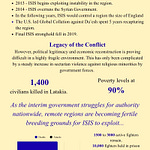

Since 2011, fighting between the KIA and Tatmadaw has decreased but still continues. However, the fighting in the Kachin State has led to significant displacement of the population in Northern Myanmar. Forests and land have been destroyed by fires, forcing people into Internally Displaced Persons Camps (IDPs). The Myanmar Campaign Network reports 1.4 million people in IDPs, with 36% of these camps denied UN humanitarian aid by militant groups. Moreover, Women and girls in these camps face higher risks of human trafficking and sexual violence. Additionally, there is widespread drug and alcohol use by displaced men, resulting in an increase of domestic violence (Kuehnast & Sagun, 2021).

The Tatmadaw's Weaponization of Gender, Ethnicity, and Religion in Myanmar

Conflict and displacement create spaces of impunity, allowing criminals to evade justice. This is especially relevant for the Tatmadaw, an army known for abuse and violence. This military has a widespread culture of tolerance towards humiliation and the deliberate infliction of severe physical and mental pain, often through rape and sexual violence targeting women (Kuehnast & Sagun, 2021). The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights reported that Tatmadaw's military operations against the Rohingya (another religious ethnic group in Myanmar) and ethnic groups in Northern Myanmar employ large scale brutal and sexual violence as part of a deliberate strategy to intimidate, terrorize, and punish the civilian population. The Tatmadaw dehumanizes gender, ethnicity, and religious identity of minority groups across Myanmar as a tactic for domination. Their clearance operations in Northern Myanmar, especially Kachin State, involve rape and violence as 'a tactic of war' (Human Rights Council, 2019).

In one notorious case in 2011, a 28 year old mother named Sumlut Roi Ja was kidnapped by Burmese Army Soldiers from her home in the Kachin State (Nyein, 2015). Her location is unknown, yet it is widely believed that she was raped and murdered by soldiers who enjoy impunity in conflict areas like the Kachin State. Her case became well known for being one of the few that went to the Supreme Court, as a result of her husband who fought for justice at every level of Burma's judiciary. However, the case was dismissed in 2012 due to a lack of evidence. Roi Ja's story is just one part of a long list of women who have suffered from abuse at the hands of the Tatmadaw (Nyein, 2015).

In 2019, the Human Rights Council published a report on "Sexual and gender-based violence in Myanmar and the gendered impact of its ethnic conflicts." In a section of this report, they interviewed 65 survivors, families of survivors and victims, witnesses, and experts from Northern Myanmar, detailing their experiences since 2011. These findings highlighted the horrors survivors faced in Myanmar at the hands of the Tatmadaw.

These stories, too graphic for this blog post involve young girls subjected to strip searches, gang raped, forced to labor, and kept as sexual slaves. It is heartbreaking to hear these stories. This experience is not just unique to women; many men face similar sexual violence. These men are often accused of involvement with the KIA and forced to confess through abuse, leading to charges under Unlawful Association Section 17(1) (Human Rights Council, 2019).

Barriers in Reporting and Punishing Sexual Violence

Moreover, there are minimal consequences for the Tatmadaw regarding rape and sexual violence. The Tatmadaw leadership does not punish rape related to military activity and covers it up. Soldiers are protected under article 381, which suspends the right to justice during emergencies (Human Rights Council, 2019). In one case, after a survivor reported a rape, the Tatmadaw leadership visited the survivor's home and abused relatives while confiscating property.

Furthermore, survivors struggle with a pattern of victim blaming. When a rape is reported in Northern Myanmar, it's publicized. Victims struggle with humiliation. One survivor says, "the victim is always pointed at and everyone knows she was raped." (Human Rights Council, 2019) This makes it difficult to report sexual violence levels in Myanmar. Women's organizations are more reliable for reporting incidents of sexual violence. They provide treatment after incidents, which is rare in most communities. Yet these organizations are hard to access.

Addressing Human Rights Violations in Myanmar

It is clear that the Tatmadaw has violated international human rights law and committed war crimes in Myanmar. The international community must make significant progress to address this issue. This could include recommending a criminal tribunal to the International Criminal Court or to pressure the Government of Myanmar to change through the release of an official statement.

Additionally, the Government of Myanmar should make efforts to address the issue. This includes eliminating the culture of rape in the Tatmadaw the culture of rape through explicit claims to soldiers against the use of sexual violence. A judicial framework must be established for civilians to report incidences of rape so an investigation can occur and action can be taken. Moreover, there is a pressing need for all displaced people (especially survivors) to access basic medical services, this includes sexual health and psychological support. The Government should ensure that international organizations have access to all IDP camps to provide humanitarian aid.

In this episode Ava discusses the Kachin expereince in Myanmar She is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Department of War Studies, King’s College, London. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.