Restoring Identity through Music in Post-Conflict Societies

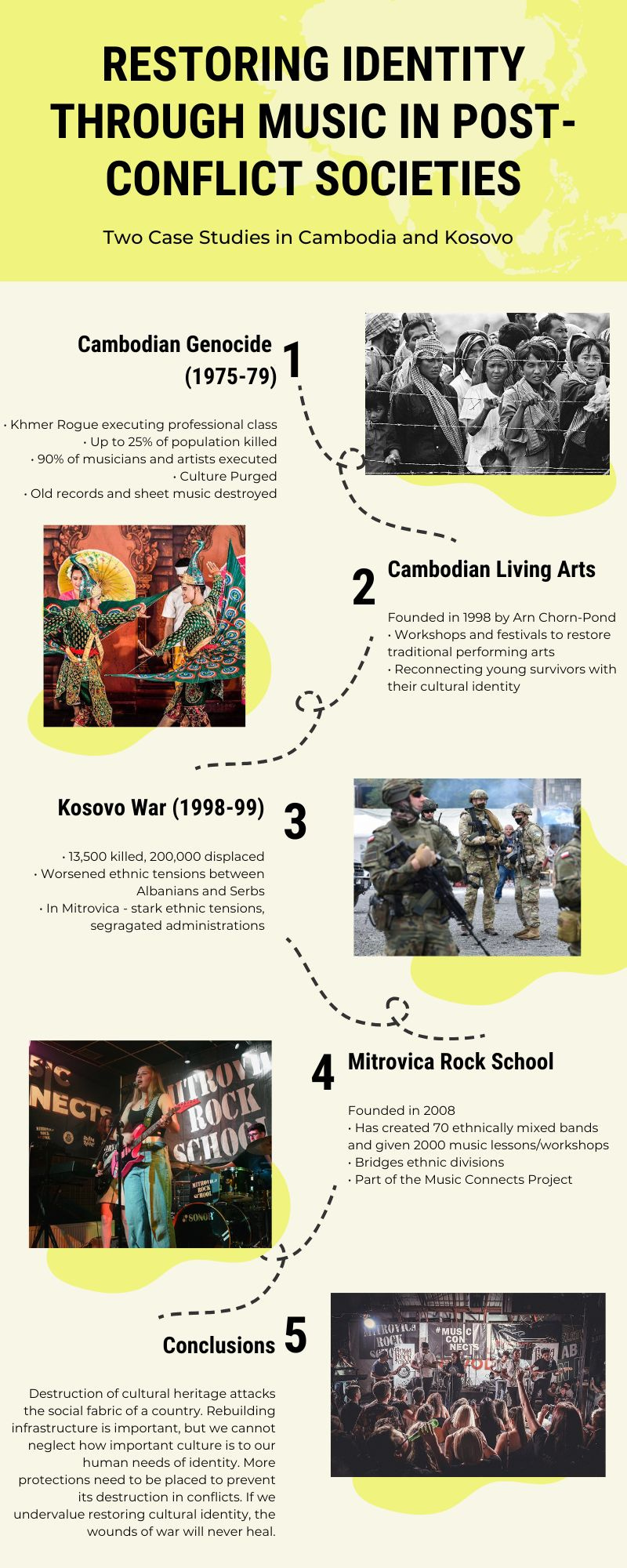

The scars of conflict extend beyond physical destruction. During the Cambodian genocide (1975-1979), the Khmer Rouge killed up to 90% of the nation’s musicians, endangering the cultural heritage of traditional performing arts. In post-conflict societies, the immediate priorities are security, stability, and safety, leaving cultural recovery sidelined. Those who remain to carry forward the torch of artistic expression navigate a landscape of depleted infrastructure, economic hardship, and the displacement of other creatives.

Cultural objects, tangible or intangible, anchor a person's sense of belonging to their homeland. When this heritage is destroyed, it strips people of their communal identity – a fundamental human need. Inevitably, losing cultural heritage makes reconciliation and peacebuilding harder. With no shared identity, the chokeholds of ethnic, religious, and political divisions are kept alive.

We all share a human need for connection and acceptance. For artists in a post-conflict environment, a deflated arts sector and a lack of opportunity for growth leaves individuals unfulfilled. Without a communal sense of belonging, artists and their consumers are left psychologically adrift and emotionally fragmented. Yet, two promising case studies in Cambodia and Kosovo show how communal music projects by NGOs can help rebuild cultural identities to unite division.

Cambodia: Cambodian Living Arts

'I come from a family of performers; I am the only one left'

Arn Chorn-Pond was just 11 years old when the genocide destroyed his world. Under the systematic eradication of Cambodia’s cultural elite, his parents were murdered for owning an opera company. He was placed in a labour camp where 700 children were forced to work from 5am to midnight with no food. Music was a means of survival. Cadres forced him to play propaganda songs on the flute to mask the screams of tortured and killed victims.

During the genocide, a generation of 'camp children' were born and raised in brutal forced labour camps. For them, the hostile environment of torture and violence was all they had ever known. Mental health illness and trauma among young people were a tragic but common consequence of the conflict. With little connection to life before the oppressive Khmer Rouge regime, Cambodian youth struggled to grasp their true cultural identity.

After fleeing to Thailand and the United States, Chorn-Pond returned to his homeland, Cambodia, in the 1990s. To his dismay, the country’s cultural and social fabric had been eradicated. The traditional genres of Cambodian music were on the brink of extinction. Old records and music sheets were destroyed, and the few surviving master artists lived in poverty. In 1998, Chorn-Pond set up Cambodian Living Arts (CLA) to reconnect surviving artists and preserve the performing arts traditions neglected under the Khmer Rouge.

The primary motive of CLA was to restore this disconnect young people felt. Initially, the CLA facilitated workshops with surviving master artists to transfer their knowledge to a younger generation. Over time, a successful cultural revitalisation of traditional genres allowed CLA to shift their mission from preservation to developing a sustainable flourishing arts sector.

Today, CLA works with the Cambodian government to write a new arts curriculum and arts education training curriculum. CLA has supported young musicians through grants, workshops, scholarships, fellowships, and professional development training. CLA's ability to reconnect post-conflict survivors with a shared cultural identity has restored dignity among young musicians to help soften intergenerational trauma.

As Chorn-Pond says, 'how can we find healing if we don’t even know who we are?'.

Kosovo: Mitrovica Rock School

'We just want a place where we can be normal.'

Mitrovica, in northern Kosovo, is often described as Europe’s most divided city. During the Kosovo War (1998-99), part of the Yugoslav Wars, ethnic Albanians sought independence from the Serbian-led Yugoslav state, leading to intense regional violence. Kosovo’s 2008 independence declaration further deepened these divisions.

Tragically, the Ibar River now symbolises a bleak divide in the city, with ethnic Serbs in the north and ethnic Albanians in the south. Each community has separate administrations, perpetuating segregation in education, governance, and daily life. Despite over 7,000 NGOs in Kosovo since 1999, their efforts to improve inter-ethnic relations are undermined by scepticism and fear of community backlash among the youth.

Enter the Mitrovica Rock School (MRS). Founded in 2008, it aims to unite Serbs and Albanians through participatory music. The school operates from school branches on either side of the river. Students from all over the city join the school to attend music lessons and form ethnically mixed bands. To date, the rock school has formed 70 ethnically mixed bands, and given 2000 music lessons, workshops and band sessions per year.

The success of MRS lies in the friendships that blossom among its students. A 2021 evaluation of MRS’s impact found that shared creative tasks, like composing and recording original songs, strengthened bonds within its members through teamwork and negotiation. When members from diverse backgrounds collaborated, they developed a shared sense of purpose and a new collective identity.

Rehearsal spaces and studios provided a ‘bubble’ of safety for the youth. In everyday life, social pressures make it hard for young people to form cross-community friendships. It is no surprise many friendship groups here are typically homogenous. Yet, these rehearsal spaces offered a supportive environment for experimenting with new social interactions. Over time, these cross-community bonds normalised interaction in unfamiliar regions. One student said that meeting fellow MRS members provided comfort and familiarity when exploring parts of the city outside their ethnic enclave.

MRS is also part of the Creative Europe Music Connects project, launched in 2022, which connects Mitrovica youth to musicians from other Balkan countries. This includes a similar project in North Macedonia called the Roma Rock School, where Roma and Macedonian youth form ethnically mixed bands. Music Connects also links Mitrovica youth with artists and cultural organisers in Berlin and Brussels through residencies at the Balkan Trafik festival, and with students from the Dutch Rockacademie, who share similar music career dreams.

These connections help unite young people in Mitrovica by focusing on their talent, rather than their ethnic identity or political affiliation. In spite of a hostile environment, young artists with similar dreams can reach their full potential and find a sense of purpose.

Concluding Thoughts

The music projects in Cambodia and Kosovo show how culture can help reconstruct shared identities and bring people together in post-conflict societies.

While this article focuses on music, we should acknowledge the wider significance of culture in shaping identity. Current conflicts continue to threaten cultural heritage. In the Russo-Ukraine War (2014-), Russian forces have stolen over 28,000 artworks from the Kherson Regional Museum in Ukraine, and destroyed 50,000 books in a Kharkiv printing house. In the Gaza War (2023-) more than 200 buildings of cultural significance in Gaza have been destroyed by Israeli forces, along with the deaths of 28 Palestinian artists in the war. In the 2021 Taliban offensive, combatants have banned music in public and seized traditional instruments across the country.

International laws, such as the 1954 Hague Convention and 1970 UNESCO Convention, are designed to prevent the destruction of cultural heritage in conflict. However, many academics argue over their effectiveness among non-state actors with no obligations to abide by.

Destruction of cultural heritage attacks the social fabric of a country. Rebuilding infrastructure is important, but we cannot neglect how important culture is to our human needs of identity. More protections need to be placed to prevent its destruction in conflicts. If we undervalue restoring cultural identity, the wounds of war will never heal completely.

In this episode George discusses the impact music has on the identity of post conflict communities. He is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Oxford University Career Services. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.