Navigating Post-Conflict Challenges in the Solomon Islands: Foundations to Sustainable Recovery

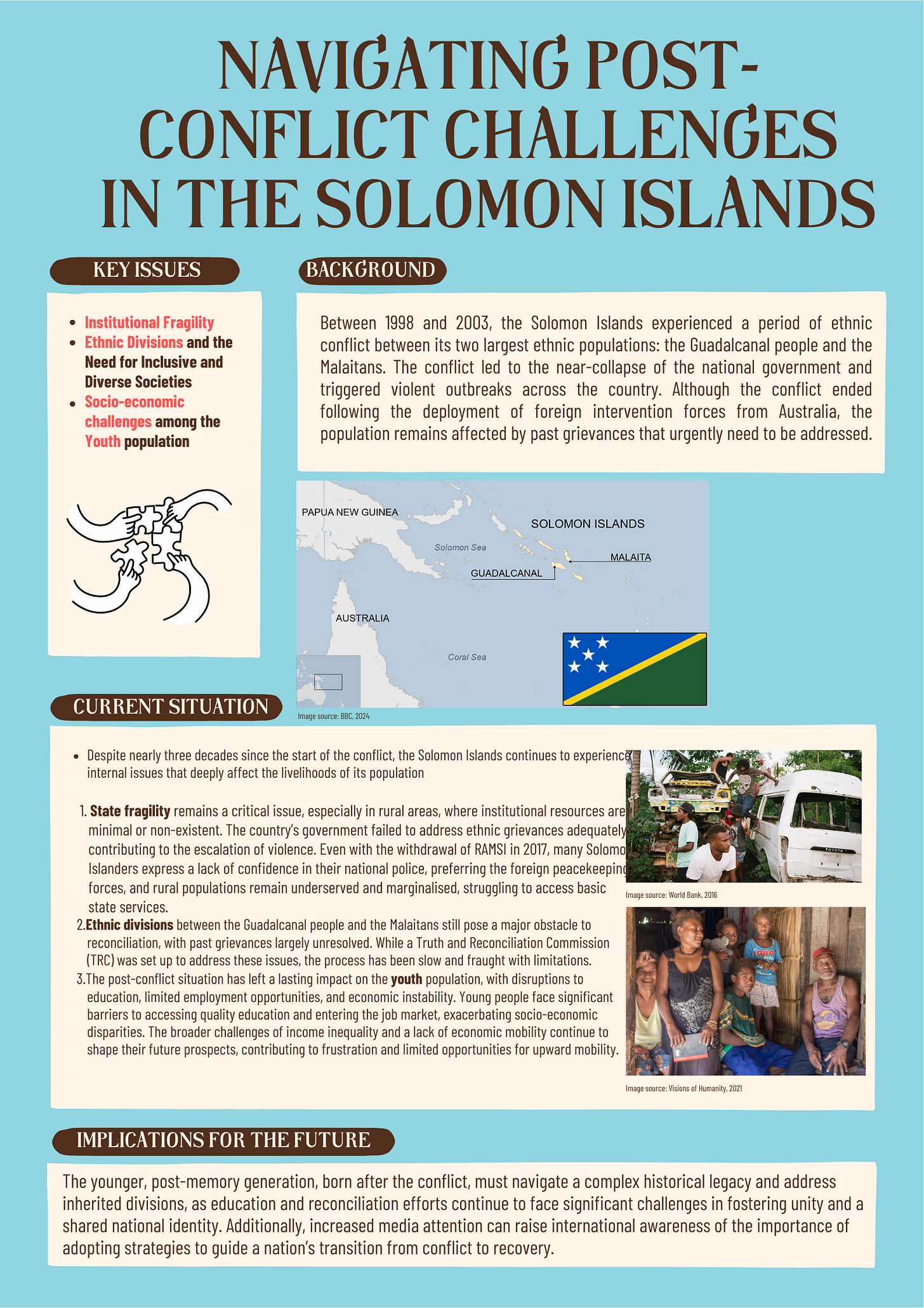

The turn of the century in the Solomon Islands witnessed a five-year period of civil unrest, fueled by the long-standing ethnic tensions between the island's two largest communities - the Guadalcanal people and the Malaitans. Between 1998 and 2003, these rivalries escalated into a violent conflict that destabilised the Pacific nation, ultimately necessitating foreign intervention to establish a ceasefire. Despite the formal end of hostilities, the legacy of conflict continues to weigh heavily on the younger generations. Ongoing challenges such as fragile institutions, incomplete reconciliation, and persistent socio-economic hardships, particularly in education, employment, and healthcare, hinder progress and recovery. In this context, what pathways can the Solomon Islands pursue to achieve long-term peace and development?

I first heard about this issue in high school through my Australian Global Politics teacher. He explained that he was involved in the peacekeeping mission to the Solomon Islands, termed the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands or RAMSI for short. After an in-depth discussion about the specific situation he was deployed to address, I was surprised by the lack of media coverage on this issue. When I went home, I began, as I normally do, to search for a video documentary that might delve deeper into what we had discussed. Despite various attempts to find more recent uploads, the latest videos I came across were over a decade old. This puzzled me, considering the conflict had occurred less than twenty years earlier. I thought that surely, there would be media coverage of its aftermath? I then expanded my search to other forms of publications, becoming increasingly curious about how the conflict might have affected the younger generation. As a Cambodian whose family underwent the Khmer Rouge Genocide, I find a quiet resonance with issues of this nature, particularly those involving post-conflict recovery.

Home to a mosaic of cultures, the Solomon Islands is a culturally diverse and geographically widespread nation. Although the official language of Solomon Islands is English, only around one to two percent of the population speaks it. Instead, the most commonly spoken language is Solomons Pijin, underscoring the significant cultural and linguistic divides the country must address as it strives to forge a cohesive national identity that truly reflects its diverse population (Equal Rights Trust, 2016). The conflict which emerged in 1998 is commonly referred to as the “Tensions”. In October 1978, three months after the Solomon Islands gained independence, a group of Guadalcanal people formed a movement to demand the establishment of a state government for the province of Guadalcanal. This movement was largely driven by grievances over the influx of immigrants, particularly from the nearby island of Malaita. The escalation of ethnic tensions between the two groups was a product of the failure of the national government to adequately address the various demands of the Guadalcanal people, who felt their island was being disturbed by foreign islanders. Thus, the eruption of a violent conflict by the Guadalcanal people, initially called the Guadalcanal Revolutionary Army, and later, the Isatabu Freedom Movement (IFM) seemed inevitable. Insurgencies from the IFM led to the displacement of over 30,000 Malaitans and a rising civilian death toll. In response, the Malaitans formed Malaita Eagle Force (MEF), a rival militia group whose goal was to counteract the IFM. Ethnic violence between the two parties further led to a near-collapse of the state government, whose final resort was to request foreign intervention from the Commonwealth countries of Australia and New Zealand. Ultimately, the Townsville Peace Agreement, brokered by Australia and New Zealand, was signed, marking a step in the positive direction for the people of the Solomon Islands. However, it was not until the deployment of the Australian-led peacekeeping mission, RAMSI, in 2003 that meaningful stabilisation began. Active between 2003 to 2017, RAMSI supported the restoration of the country’s rule of law and strengthening key sectors such as health and education. These efforts were positively received by the locals (Leith, 2011).

A withdrawal of the mission in 2017, therefore, brought about concerns from the people of the Solomon Islands over the country’s ability to withstand post-conflict challenges on its own. A withdrawal of the mission in 2017 raised concerns among the Solomon Islanders about their country's ability to withstand post-conflict challenges independently. One of the key reasons the Solomon Islands descended into ethnic conflict was the government's failure to adequately address the needs of its people. While factors like migration and land disputes were important triggers, the outbreak of violence can be traced back to a specific incident: the murder of a Guadalcanal woman on April 21, 1998, with suspected killers from Malaita (Foukona, 2024). Instead of adopting legal mechanisms to address the issue, the then Deputy Premier, Nollen Leni, took an unconventional approach by holding the entire Malaita Province accountable for the murder. This broad condemnation transformed the conflict from a criminal justice issue into a communal one, further exacerbating the existing tensions between the two largest ethnic groups in the country. Hence, it is unsurprising that the Solomon Islands continue to struggle with institutional fragility and widespread public distrust in the aftermath. News reports have indicated that many Solomon Islanders still place greater trust in the mission’s police force than in their own national police. At the same time, rural citizens voiced concerns over difficulties in accessing state services, with much of RAMSI’s development work focused on central government agencies in the capital of Honiara. This leaves those in rural areas with some isolated police posts across selected areas. Despite access, individuals often feel marginalised or insufficiently supported by the system. Given the Solomon Islands’ unique cultural context, effectively bridging formal institutions with traditional leadership structures is essential to fostering a genuine sense of community. However, the Western-designed, bottom-up approaches to state-building often undermine existing local strengths instead of reinforcing them, an issue that needs urgent attention.

At the communal level, post-conflict reconciliation in the Solomon Islands still demands further effort to promote inclusivity and address long-standing grievances between ethnic groups. Inspired by South Africa’s post-Apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), the Solomon Islands adopted a similar model to build a more unified national identity. However, these bureaucratic processes are often time-consuming and emotionally taxing, with many gaps and limitations remaining unaddressed. The Solomon Islands TRC was mandated to promote national unity by examining the root causes, nature, and impact of human rights violations between January 1998 and July 2003 (Solomon Islands Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2012). Yet, the link between justice, truth, and reconciliation is not always straightforward. While TRCs aim to empower victims, they can also become spaces where marginalisation and existing power asymmetries are reinforced, ultimately undermining victims’ expectations. As some scholars argue, concepts like justice and reconciliation take on different meanings depending on the cultural context in which a truth commission operates. Transitional justice (TJ) frameworks remain shaped by Western academic and institutional power, with funding often coming from Global North countries. This international influence has led many post-conflict states to follow a global justice model combining top-down mechanisms with limited bottom-up, locally grounded approaches

Moving onwards, the international community, and the government of the Solomon Islands in particular, need to recognise and address the pressing needs of the younger generation. Among these, are issues regarding youth employment and livelihoods. While many initiatives focus on developing soft skills, these do not necessarily lead to stable or sufficient incomes. Moreover, technical and professional roles are often filled by expatriates rather than locals, further limiting opportunities in an already limited job market (UNDP, 2018).

The post-memory generation, born after the conflict, is often overlooked. They bear with them the weight of having to reconstruct fragmented narratives of their family’s and nation’s past. Efforts to rebuild the nation, whether through reconciliation or improvements in health and education, must confront this challenge directly. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommended that its report be integrated into school curricula to help students understand the civil conflict. Yet, in both post-conflict Solomon Islands and Bougainville, teachers and students have frequently avoided these discussions. Silence was often preferred, with many turning instead to everyday relationships and routines as their way of making sense of justice. This reluctance reflects the profound complexity of healing after violence. For peacebuilding to be truly effective, education must foster truth-telling, empowering the younger generation not only to remember but to reimagine a more unified and inclusive future.

In this episode Sinamaline discusses the Solomon Islands and the aftermath of the civil war. She is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Department of War Studies, King’s College, London. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.