War, a ginormous ripple in the sea, and the tale of the people who missed their boats

Ethnic violence: A brief history

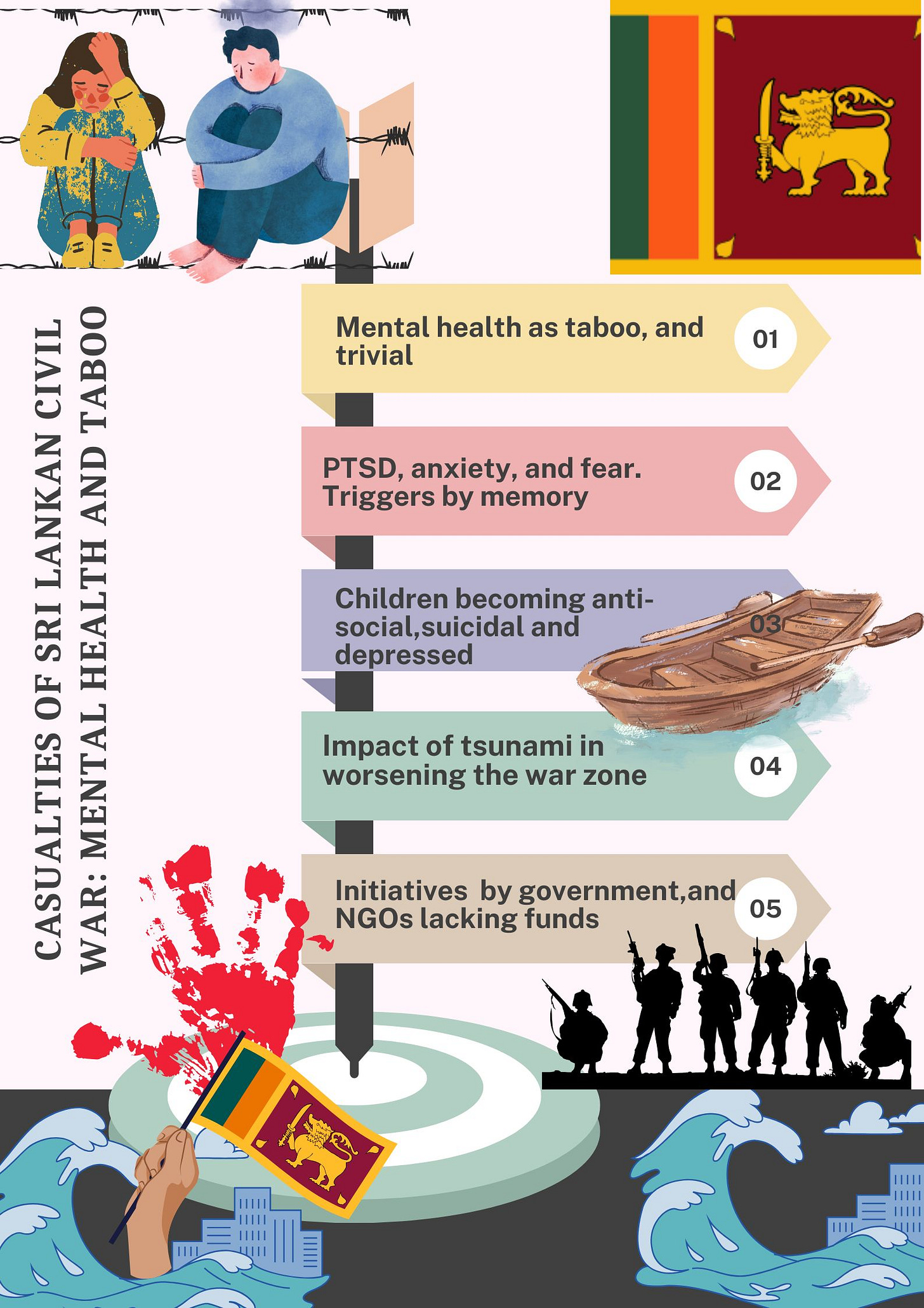

The twenty-six-years-long Sri Lankan civil war was one of the most horrific blood baths that ravaged the country. The aftermath of the war was more distressing, as the people were grieving the loss of their family, home, and hope for the future. Among death, and physical injuries, their mental health deteriorated. Three decades of constant warfare took a toll on an entire generation of youngsters. A substantial part of their lives was scarred with fear, anxiety, and restlessness. This aspect of “collective trauma” is often neglected in most of the post-conflict building societies, since greater significance is directed towards physical and material rebuilding of the societal fabric. This becomes notably sidelined in countries and communities where mental health is generally neglected, and trivialized. In Americanah, Adichie alludes to how the protagonist’s family downplays the seriousness of mental health just because it is a ‘western concept’. Mental health discourse is labelled as a taboo among many cultures (Harmes, 2017). This holds true, even in the wake of the twenty first century, where many countries advocate for mental health awareness.

The Sri Lankan civil conflict began in 1983, and lasted until 2009. However, the root of the dispute can be traced back to the era of the Chola dynasty, when the Tamil community from South India moved to what was then Ceylon, for trade. Later, their population and subsequent influence increased as British colonizers brought in labourers from Tamil Nadu to work in tea, coffee, and rubber plantations. This paved way for ethnic tension, and complications regarding power dynamics. The need to assert dominance was important for both the parties - a sense of true belonging for the Sri Lankans, and years of historic ties for the Tamil community. The linguistic and religious elements of difference fuelled the already raging fire of ethnic dispute. The driving force of the social hierarchy led to the civil dispute that caused more damage than expected.

War, tsunami, and deteriorating mental health

The civil-strife was marked with horrors of murders, rape, pillage, and forced conscription of children who were used as suicide bombers. Many managed to leave the country, embarking on a new journey as boat people, while the rest were trapped amidst the chaos of assassinations, and bombing. The life of the refugees was not easy either, as it was difficult for them to assimilate into the new cultures, and take advantage of the new opportunities. Building their life was a laborious task as they had to encounter PTSD, sleeplessness, and constant fear of death. The residents who were left behind were gravely affected, since they had to constantly witness the ruins of the war, which inevitably triggered their memories, and left no space or time to heal. The recollections are so severe, intense and vivid that the victims believe to be back amid the ‘atrocities’ (Elbert and Schauer, 2002).

During the war, a number of civilians were used as human shields, by both the parties, exposing them to life-long trauma, which would take years of medical care to recover from. Studies show that suicide among refugees was another problem that had to be tackled by the government’s intervention. In an interview, Mohan Panneer Selvam - a victim, describes how his grandmother was shot, and thrown into the house which was later burnt. As he speaks, his voice breaks, and reverberates with pain while recounting the account of his father trying to “throw” his eight-years-old younger sister out of the window. This is one of the hundreds of testimonies underscoring the brutality of war and the extent to which it could impair the wellbeing of those affected.

The plight of the people increased manifold when the 2004 tsunami struck the island. The Ministry of Social Welfare has declared that an estimate of thirty thousand people were killed during the natural disaster. For a community already warped by war, this was an unexpected blow, causing serious damage- both physically, and emotionally.

Children were the most harmed, because they bore the brunt of the war- being forced to balance their academic pursuits, and their role as the breadwinners in the families without male figures. A number of widows left the country, to work in the Middle East, in order to support children. These children grew up without parental figures, facing their demons without familial support.

The element of “long term displacement” could take up to two years, making the kids miss out on their lessons, re-take classes, and feel inferior to their peers who are younger than them. This could also constitute to their sense of subservience, causing issues in their adult life. Owing to the ethnic tensions the inability to socialize with peers their age, from other communities affected the children during the formative years of their life. They were fraught with cynicism, and mistrust. This constant vigilance was an influential factor in their lives, and deteriorating mental health.

An article in the British Journal of Psychiatry elucidates that the civilians of Sri Lanka were severely affected by “PTSD, depression, and anxiety.” This study elaborates that the respondents relied on their ‘strength’, ‘family and friends’, ‘religious practices’, and ‘western- style hospital’ for recovery. This discloses how the victims are constantly relying on community to cope with the piling trauma. This sense of kinship from the society becomes the core of sustenance. Harmony, a sense of belonging, and social connectedness become the fabric of wellness. In contrast, a report by Indranil Sahoo and team sheds light on how the refugees camped in India lack “familial and social support networks.” Both these studies reveal how the aspect of social support could influence the making or breaking of the re-establishment of peaceful living, and a journey towards a better life.

Humanitarian aid by NGOs, influenced health workers and inert laws

The UK Sri Lanka Trauma Group has initiated a number of plans, and policies to combat the mental health problems of the citizens. Their efforts have resulted in the initiation of the M. Phil course in Clinical psychology, at the University of Colombo. Training and curricula were developed to effectively implement the projects undertaken by World Vision and Samutthana, for the victims of war. In this regard, the era of side lining mental health has drawn to a close, wherein the government and the people have realized the significance of mental health wellbeing.

The victims have been provided with help, but their plight was deeply disturbing that it affected the healthcare workers. The health workers opine that their perspective towards their clients’ transformation is nothing but “personal transformation” (Satkunanayagam et al, 2010). This was in addition to the workers being susceptible to extreme emotions like sadness, frustration and anger while working with the victims of war. Their indignation towards the ‘injustice’ of war was immense, and they overcame it through the act of service: helping the victims heal, and re-build their lives. This study also brought to light, how the personal experiences of the people altered the psychology of the healthcare workers, by elucidating on how the human psyche is an interconnected and closely knit web of emotions. Irrespective of anger, through sheer commitment, the workers championed the emotional surges, and helped the victims overcome the ghosts of their past.

A report by WHO, published in 2012 states that mental health review committees have been established in all the districts of the country, where doctors, social workers, and representatives from the communities convene to talk through the progress of the support, and areas that require swift intervention. The report also highlights that the inadequate funds allocated to these programmes are insufficient. This calls attention to how the deficit funds would negate the efforts put in to date. In 2017, it is reported that only 0.52 trained psychiatrists were available, per 1,00,000 population. The number of ‘clinicians’ should be increased, while reforming the mental health law, and prioritising the mental health act of Sri Lanka (Hapangama et al, 2022). The government should address these problems with efficiency, making the laws accessible, and functional.

Restoring glory, and awaiting the return of the boat people

It is nearly fifteen years since the end of the war, yet the trauma is still acute. The victims who suffer because of the lack of mental health support live through their pain in silence, and it is important for the government to closely inspect, and render support. Constant monitoring and vigilance by the government, policy makers, and medical professionals would help the people rebuild their lives, and realize that their life is worth living. Given that social bonds, love, compassion and support are intact - weapons, and waves of destruction would not crush the spirit of the people who missed their boats. They would restore their homes to their former glory, and await the return of their kin who were forced to board on boats and suffer in countries far away from their island nation.

In this episode Nishiha discusses the mental health and collective trauma in the aftermath of the 26 year Sri Lankan civil war. She is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Department of War Studies, King’s College, London. This article was edited using Lex.page. Image with Napkin Ai

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.