Bread, Water, and War: The Story of Yassir Al-Bakar and Yemen's Humanitarian Collapse

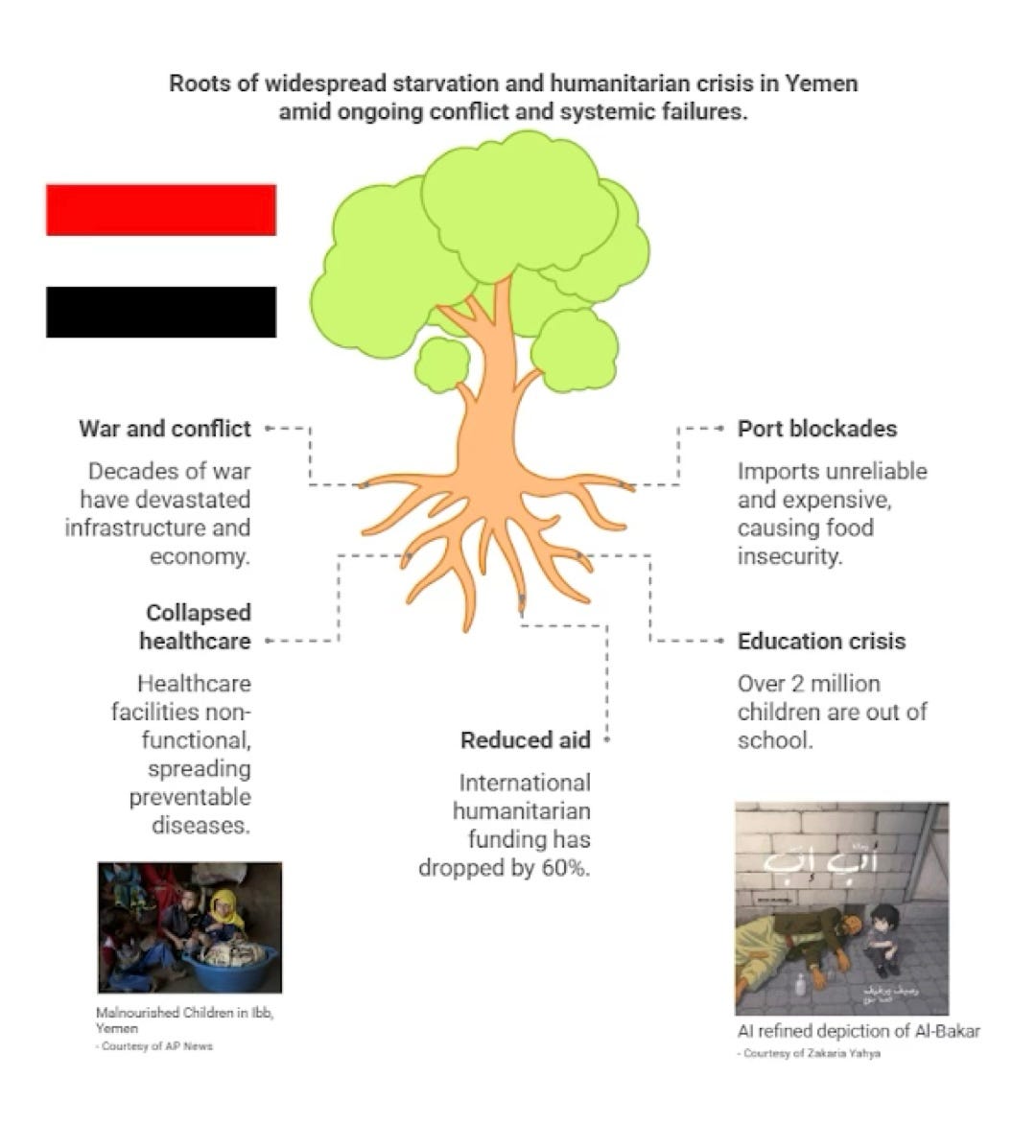

In Yemen, where survival often hinges on the slimmest of margins, the death of Yassir Ahmed Saleh Al-Bakar stands as a stark testament to a nation's descent into despair. A father of four from rural Ibb, Yemen, Yassir succumbed to starvation on a sidewalk during Eid al-Fitr, his body found beside an unfinished piece of bread and an untouched bottle of water. His young son, Ammar, stood nearby, holding a piece of cake and juice given by a passerby, unaware that his father had already passed away. This heart-wrenching scene, captured and shared widely on social media, has ignited public outrage and drawn attention to the systemic failures that have pushed millions of Yemenis to the brink. Al-Bakar's death has ignited public outrage, with many Yemenis blaming the Houthi militia for systemic economic collapse and neglect that have pushed thousands to the brink of starvation. Critics accuse the group’s leadership of siphoning national resources, withholding salaries, and stripping citizens of their basic right to survival, all while militia elites live in opulence. This incident underscores the severe humanitarian crisis in Yemen, where millions face acute food insecurity, and preventable deaths from hunger are becoming alarmingly common. Yemen is not a place that makes headlines often, despite being the site of one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. A country of roughly 33 million people, Yemen has been devastated by more than a decade of war, first between the Houthi rebels and the internationally recognised government, and then through the involvement of regional powers like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Iran. The consequences have been catastrophic. Over 70% of Yemen’s population — more than 21 million people — now depend on humanitarian aid to survive. Before the war, Yemen was already the poorest country in the Middle East. But since 2015, the collapse has been near-total. As of 2025, over 4.5 million Yemenis are internally displaced, living in tents, unfinished buildings, or makeshift shelters. These are people who once had homes, jobs, schools. Now they survive on rations, if that.

Food and Water: Scarcity in a Land of Need

Let’s begin with the basics: food and water. Yemen imports 90% of its food, but since the war began, port blockades and infrastructure damage have made imports unreliable and expensive. The UN estimates that more than 17 million Yemenis face acute food insecurity. In some areas, children eat once every two days. In others, they survive on bread soaked in water and salt. Water is just as dire. Only 40% of Yemen’s population has access to safe drinking water. In some towns, families walk for hours to find a well — and even then, it may be dry or contaminated. Cholera outbreaks have claimed thousands of lives, and with climate change accelerating drought cycles, Yemen’s water crisis is likely to worsen. When I read that the average Yemeni uses less than 20 litres of water per day — compared to over 300 litres for the average American — it felt unfathomable. But then I remembered the image of Yassir Al-Bakar, collapsed on the street with an untouched water bottle beside him, and it became all too real. The war has decimated Yemen’s health system. More than half of the country’s healthcare facilities are non-functional. Those that remain often operate without electricity, clean water, or essential supplies. Doctors perform surgeries by torchlight. Babies are delivered without anaesthesia. Cancer patients receive no chemotherapy, and there’s a national shortage of insulin. Meanwhile, the spread of preventable diseases — cholera, measles, malaria — is accelerating. Over 2.5 million children under five are acutely malnourished, including nearly 500,000 at risk of death. The World Health Organization reports that malnutrition is now the leading cause of death for children in Yemen.

Access is even worse for women. In rural areas, pregnant women often give birth at home with no medical assistance. Many die from complications that would be treatable elsewhere — haemorrhaging, infection, obstructed labour. Under Taliban-style restrictions imposed by conservative factions in northern Yemen, women often need male guardians just to visit clinics, echoing policies seen in Afghanistan.

Education: A Lost Generation

Education is often framed as a long-term solution, but in Yemen, it’s a short-term crisis. Over 2 million children are out of school, and many more attend only sporadically. Bombed-out school buildings, unpaid teachers, and lack of supplies make learning nearly impossible. Even worse, economic hardship has forced many families to pull children — especially girls — from school to work or marry early. UNICEF reports that 44% of children in Yemen drop out before secondary school, often to engage in labour or caregiving. This loss has devastating implications. Education is a stabilising force in conflict zones — a place for structure, meals, safety, and psychological healing. Without it, trauma festers, and futures shrink.

The war has displaced millions. Many live in IDP camps, half-finished buildings, or even in public squares. Shelter conditions are deplorable: torn tents, no privacy, limited sanitation. In the winter, children freeze; in the summer, they suffer heatstroke. Gender-based violence and exploitation are widespread, especially among unaccompanied girls and widows. The legal limbo of IDPs also bars them from many services. Without identification, they can’t register for aid, go to school, or even move freely. It creates a vicious cycle: no ID means no support, and no support means continued displacement. Yemen’s infrastructure is not just damaged — it is shattered. Power grids, sewage systems, internet networks, and transportation corridors have all been repeatedly bombed or left to decay. Rebuilding any of these requires coordinated investment and political stability — two things Yemen lacks. Much like in countries such as Afghanistan, where international aid is limited by sanctions and lack of recognition, Yemen’s humanitarian actors are often forced to operate outside state systems. This limits their ability to create long-term solutions. It also means that NGOs, not governments, are laying water pipes, repairing roads, or staffing hospitals.

The international community plays a critical role, but aid is drying up. According to Save the Children, international humanitarian funding for Yemen has dropped by 60% since 2019. The U.S. and E.U. have both cut contributions due to competing global crises, while Gulf countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE — once major donors — have slashed their support by over 90%. This drop in funding means ration cuts, medicine shortages and halted reconstruction. It also raises the ethical question: is humanitarian aid being used as leverage in broader political games? On the ground, the impact is immediate. Families lose food vouchers. Clinics close. Education programmes are suspended. It sends a chilling message to Yemenis: even survival is conditional.

Still, there is resilience. Community-led projects are emerging in cities like Taiz and Ibb — small collectives repairing schools, planting gardens, purifying water. Yemeni women have started local bakeries, textile co-ops, and neighbourhood tutoring circles. These efforts are modest but vital. They restore dignity and agency. International groups like the UNDP are supporting such grassroots initiatives, providing cash-for-work programmes and microgrants. The emphasis is shifting from charity to partnership — a hopeful sign for a post-conflict Yemen.

To talk about human needs in Yemen is to talk about survival — yes — but also about dignity. Shelter is not just a roof. Food is not just calories. Water is not just hydration. They are the building blocks of humanity. Yemenis are not asking for luxury. They are asking for the bare minimum — a floor, water, and a door that locks. And yet, even these remain out of reach for millions.

If the international community is serious about supporting Yemen, it must listen first — not warring factions, but to the people on the ground stitching their lives back together. Aid must be provided in a manner that upholds the dignity and fundamental rights of all Yemenis, not used as political leverage. It must be humane, steady, and grounded in rights, not charity. Only by centring the voices and needs of the Yemeni people can the international community hope to forge a path towards lasting peace and recovery.

There is still time. But the window is closing.

Bibliography

United Nations Yemen. (2025). As the crisis in Yemen deepens, aid agencies appeal for $2.5 billion for the humanitarian response in 2025. Retrieved from

https://yemen.un.org

France24. (2025). More than 19.5 mn Yemenis in need as crisis worsens: UN. Retrieved from https://www.france24.com

Oxfam GB. (2020). Donors slash funding to Yemen by half to 25 US cents a day per person in need. Retrieved from https://www.oxfam.org.uk

World Bank. (2024). Yemen’s Economy Faces Mounting Crises: Report. Retrieved from

https://www.worldbank.org

UNICEF Yemen. (2025). Education. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/yemen/education

Save the Children International. (2023). Humanitarian aid to Yemen slashed by over 60% in five years. Retrieved from https://legacy.savethechildren.net

ACAPS. (2025). Access to Reproductive Health for Women and Girls in Yemen. Retrieved from https://www.acaps.org

UNDP. (2024). Empowering local communities in Yemen through cash-for-work and livelihood support. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org

Amnesty International UK. (2023). Yemen: US military escalation and aid cuts will have catastrophic consequences for millions. Retrieved from https://www.amnesty.org.uk

In this episode Rakan discusses Yemen and how it’s coping with the day the day realities of life. He is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Department of War Studies, King’s College, London. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.