After the Blast, Before the Future:

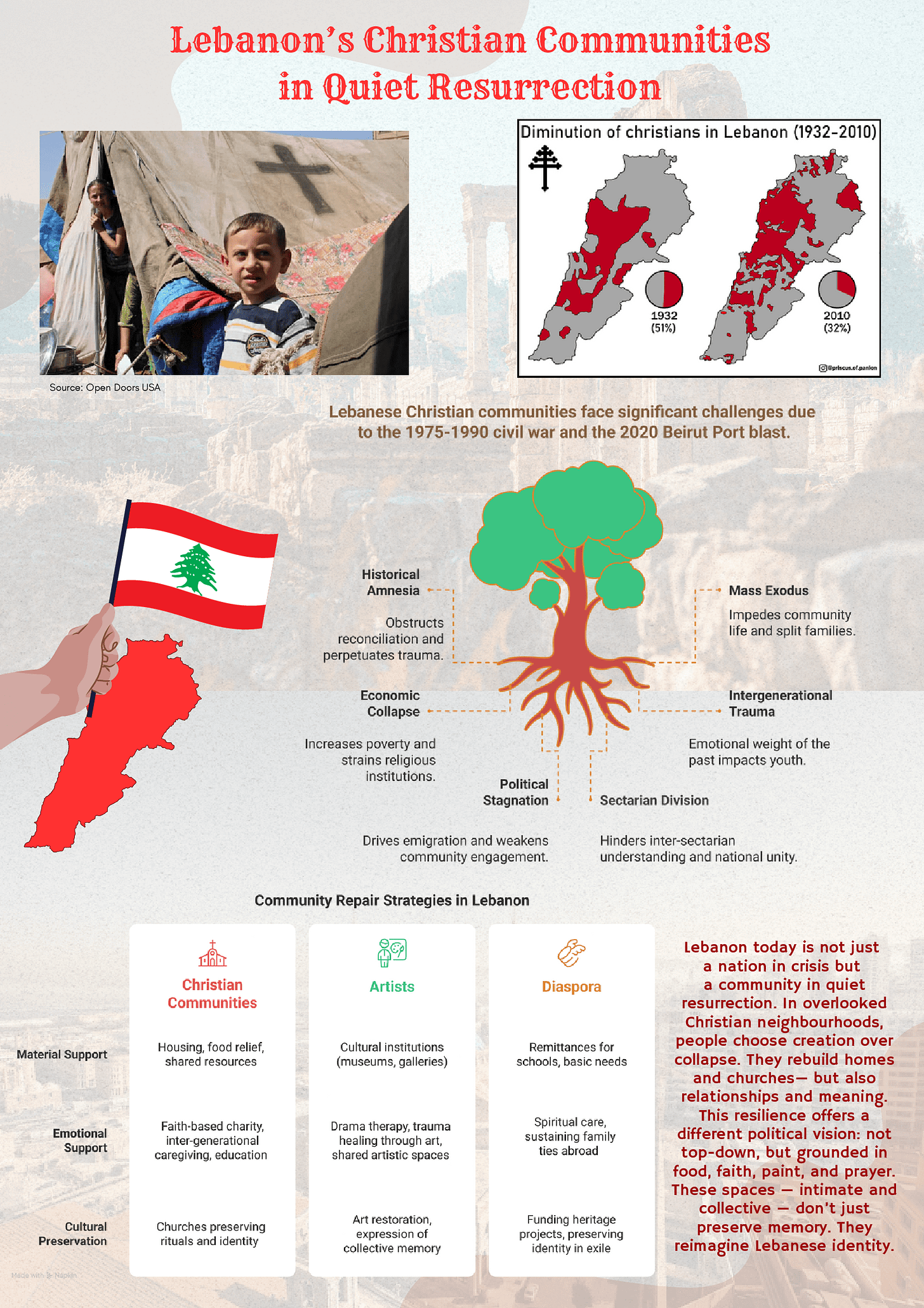

Lebanon’s Christian Communities in Quiet Resurrection

“As Christians, we believe in the resurrection. Hope, prayer, and faith are our strengths. During our history, we went through very hard times, harder than now. These are the characteristics of Lebanon.”— Maronite Patriarch Bechara Boutros Al-Raï, 2021.

Fifty Years Later: The War That Lives On

Lebanon’s wars may have officially ended decades ago, but for many, especially within Christian communities in Beirut, crisis remains a recurring rhythm. From the scars of the 1975–1990 civil war to the ongoing economic collapse, the country exists in a suspended recovery state. Once dubbed the “Switzerland of the Middle East,” Lebanon is now gravely ill, but many believe it can be healed.

April 13, 1975, is widely accepted as the civil war outbreak, fracturing the country, displacing hundreds of thousands, and creating a lasting trauma legacy. However, the war isn’t taught in schools. Instead, it survives in fragments, creating a paradox: the war is omnipresent in personal stories yet absent from national discourse. This selective forgetting reflects broader Historical Amnesia — collectively erasing significant events, and obstructing reconciliation. In Beirut, Zaitunay Bay, built over the historic fishermen’s port ruins, transformed the shoreline into exclusive real estate.

August 4, 2020, brought another rupture, with explosions at the Beirut port killing over 200 people and flattening entire neighbourhoods, especially in Mar Mikhael, home to many Christian families. The blast reignited old wounds and deepened the sense of abandonment, leaving families on the streets with no shelter or emergency care.

Between Breakdown and Belonging: Lebanon’s Living Crisis

Lebanon’s Christian communities face overlapping crises — economic, psychological, and demographic — that deepen their vulnerability.

The Beirut port blast left deep psychological wounds, especially among youth and first responders. PTSD, depression, and anxiety have surged, yet mental health care remains scarce. Much trauma is intergenerational, transmitted through emotional ruptures and silence. In Lebanon, where the civil war is grieved privately and therapy is taboo, many young people carry the emotional weight of a past they never lived — a quiet inheritance known as “post-memory” (Hirsch, 1997). But trauma doesn’t live in the mind alone. The emotional toll is compounded by material collapse: skyrocketing prices, blackouts, frozen savings, and the disappearance of the middle class. By 2020, half the population had fallen below the poverty line. Families rely on remittances, barter, or church aid for basic needs. Religious institutions — including Christian schools — are under strain, with budget cuts and teacher flight weakening what once held neighbourhood life together.

For many young Lebanese, the only option is to leave, with families scattered across continents. Among Christians, this exodus is driven by despair, political stagnation, and diaspora networks. While 60% of Lebanese youth want to emigrate, the number rises to 70–80% among Christians. Thus, churches report declining youth engagement, ageing congregations, and growing responsibilities on those who stay. The protest spirit from the 2019 uprising — a cry for dignity and national unity — has faded, and many hopeful protesters have emigrated. Beneath this lies a system that entrenches division.

Though violence has ceased, Lebanon’s politics follow a tribal logic, where power is distributed among religious communities — Christian, Muslim (Sunni and Shi’a), and Druze. What was meant to ensure balance has solidified into separation.Take the Hezbollah-run Mleeta Resistance Tourist Landmark in South Lebanon. It portrays Hezbollah as the nation’s sole defender, but other communities consider that promoting a singular narrative narrows the scope for genuine inter-sectarian understanding. Only by confronting and cross-reading one another’s stories can survivors — and future generations — hope to rebuild a future rooted in coexistence.

Faith in the Rubble: How Communities Repair When the State Fails

Despite the devastation, Lebanon’s Christian communities are finding ways to rebuild — materially, emotionally, and spiritually. Their recovery isn’t led by state reform, but by neighbours, artists, churches, and NGOs quietly restoring society.

Families share housing, pool resources, and rely on faith-based institutions for charity and dignity. Intergenerational support — grandparents, parents, children leaning on each other — has become a pillar of resilience. Caritas Lebanon and the LSESD (Lebanese Society for Educational & Social Development) form the backbone of the Christian humanitarian response. Caritas Lebanon provides food parcels, health care, and education subsidies — strengthening Lebanon’s social safety net. Its work embodies a moral ethic: “Treat people, especially the weak and marginalised, as a brother who needs help” (Matthew 25:31-46).

Then, LSESD offers psychosocial support, inclusive education, and emergency relief. Grounded in Christian values, its mission reflects a belief that compassion must cross confessional lines. Their motto, Restoring Hope to the Hopeless, is a commitment to ensuring faith becomes a bridge, not a barrier.

Elsewhere, survival depends on improvisation: in Tripoli, Basmeh & Zeitooneh’s Hydroponic Farming Project helps women and refugee families earn income and food security through climate-smart techniques — growing nutritious crops with 80% less water. These initiatives do more than meet needs — they restore control.

But healing also requires beauty, memory, and voice. Artists have stepped into the vacuum left by institutional collapse. Among them, the Zoukak Theatre Company uses drama as therapy and resistance. Since 2006, Zoukak Theatre has used performance as healing, not spectacle, but empathy for displaced people and violence survivors. Through festivals and workshops, they turn art into a space for processing trauma and imagining futures.

The Beirut Sursock Museum, devastated in the 2020 blast, also symbolises cultural resilience (Al Jazeera). In a three-year UNESCO-supported effort, although underfunded, artists restored 57 artworks. A highlight was Zad Moultaka’s immersive installation of pixelated art overlaid with glass-shattering sound, echoing the port explosion, underscoring how art can overcome Beirut’s trauma. While some questioned funding museums over housing, many artists saw heritage as essential to recovery, ensuring Lebanon’s cultural soul survives despite systemic failures. In their eyes, creativity fosters solidarity over pity, courage over fear.

Beyond museums and stages, the streets have become remembrance spaces. For instance, the Dictaphone Group rejects top-down memory projects in favour of grassroots storytelling. Their civic interventions reclaim forgotten public space and open differences: by deconstructing sectarian identity in favour of shared experience, they create space for a more open “Lebaneseness”. This isn’t the story of romanticised martyrs, but the testimony of neighbours sweeping glass from church pews and painting walls where homes stood. Lebanon’s Christian communities aren’t waiting to be saved. They’re restoring their home— brick by brick, mural by mural.

Rebuilding the Invisible: Dignity, Connection, and Affiliation

Beyond aid and infrastructure, recovery also depends on dignity and connection and rebuilding the nation means rebuilding the invisible links holding communities together. From church choirs and Sunday services to interfaith peace workshops, shared space aims to reconnect people across age and background, replacing silence with solidarity. With both youth and parents, these dialogues foster reflection on identity, emotional well-being, and coexistence. They offer mutual recognition after decades of separation, grounding the community in shared trauma and a shared future.

These ties extend beyond Lebanon. In many regions — especially in the North — the Christian diaspora sustains life: sending remittances, rebuilding schools and churches, keeping a lifeline between home and those who left. “If it weren’t for the diaspora, many Lebanese would have died of starvation” (Al-Raï, 2021). Through spiritual and material support, these networks help communities endure what the patriarch called “this moment of darkness, waiting for the sunshine.”

Moreover, artists across Lebanon assert cultural worth. Zena el Khalil exemplifies this shared emotional language. In her exhibition From Mirfaq to Vega, she mourns the loss of her ancestral homes — one bombed, the other occupied — transforming grief into collective healing. “It’s about compassion and love,” she establishes, invoking Christian symbols that resonate across Christian, Druze, and Muslim communities. Rooted in oral stories from her grandmother, her work resists fixed narratives. Instead, it plants “seeds of forgiveness,” offering a vision of coexistence relevant to Lebanon’s fractured present.

This cultural affirmation echoes elsewhere. The restored Sursock Museum, as noted, stands as a quiet act of national resistance — a refusal to let history be erased. In a country where services fail, preserving heritage becomes resilience, asserting identity through persistent care. Creative expression allows generations to imagine futures beyond collapse or emigration. Yet many Lebanese artists feel unrecognised, revealing how cultural recovery remains unfinished

Conclusion

Lebanon today is not just a nation in crisis — it is a community in quiet resurrection. In overlooked Christian neighbourhoods, even as the structures meant to protect them falter, people choose creation over collapse. They rebuild homes and churches— but also relationships and meaning. This resilience offers a different political vision: not top-down, but grounded in food, faith, paint, and prayer. As the Sursock museum architect declared: “Heritage is important. For our children and the next generations”. Their work offers not a perfect solution, but a powerful starting point: healing that begins from the ground up. These spaces — intimate and collective — don’t just preserve memory. They reimagine Lebanese identity: not despite crisis, but because of it.

In this episode Raphael discusses the aftermath of the civil war in Lebanon and the experience of the Christian community there. He is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Department of War Studies, King’s College, London.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.