Forever Displaced: The impact of ISIS on the Yazidi community ten years after the genocide

The UN defines internally displaced people as those forced to flee their homes due to armed conflict, violence, or human rights (UNHR).

Displaced individuals often remain in refugee camps due to security concerns and psychological trauma from conflict. Typically, countries with internal wars and conflicts have higher numbers of internally displaced people. In these countries, displacement can become protracted as governmental institutions fail to ensure security for minorities. Governmental shortcomings range from failure to recognise displaced communities to lack of reintegration assistance, exacerbating insecurity. The sense of abandonment by their governments coupled with the fear of persecution and renewed conflicts diminishes the willingness of displaced communities to return home.

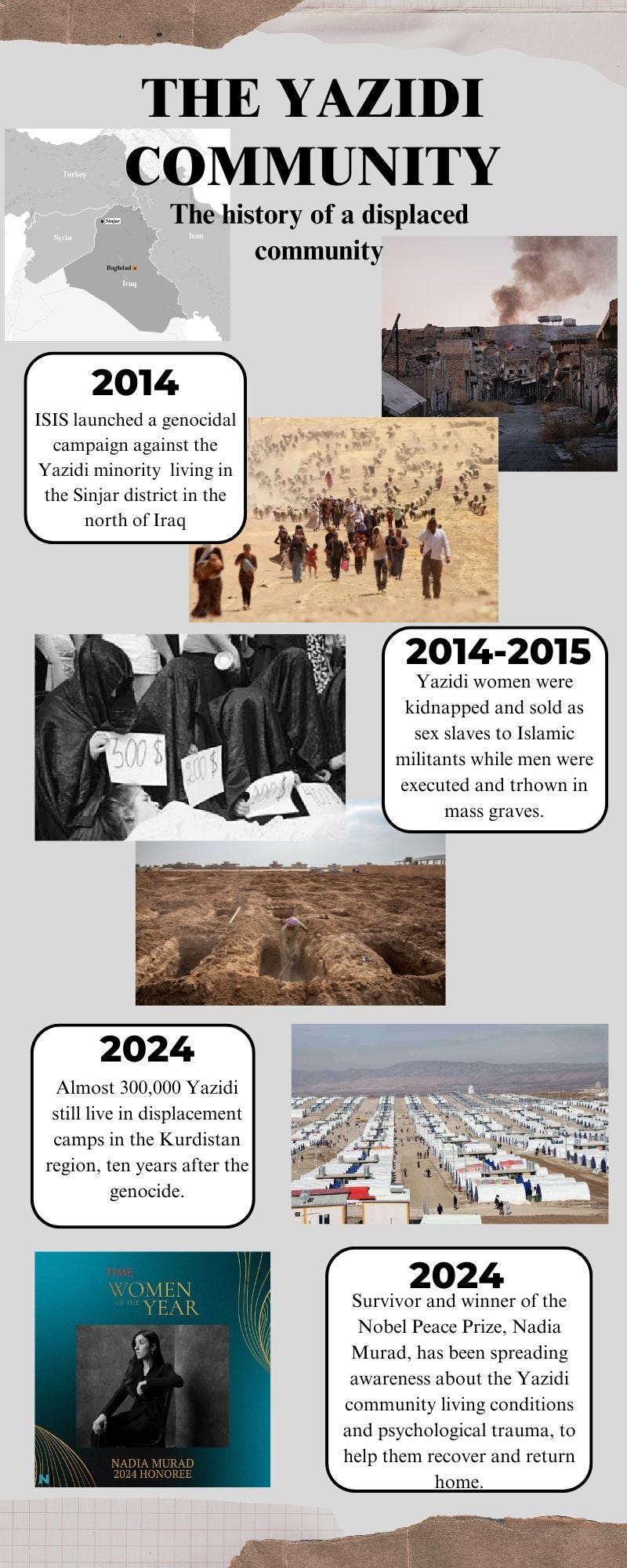

The Yazidi case.

In August 2014, militants attacked the Yazidi community in Sinjar, Northern Iraq. Approximately 12,000 Iraqi Yazidis were killed or abducted in a couple of days (OHCHR 2015). Of the 400,000 Yazidis, 2,000 to 5,500 were executed in 17 mass graves (Malik 2017). Around 7,000 Yazidis, mainly women and children, were kidnapped as sex slaves or fighters (Taylor 2017).

About 280,000 Yazidis are internally displaced, living in camps in the Kurdistan region ten years after the genocide. 3,000 women and children remain captive. Conflict, minefields, and explosives planted by ISIS hinder the return of Yazidis to normal life in the Sinjar region, exacerbating insecurity. Tensions between Yazidis and Arab tribes with ties to ISIS intensify Yazidis’ concerns about future attacks. The destruction of their homes, and the lack of services and financial resources hamper reintegration.

The Sinjar Region ten years later

Violence by the Islamic State has reshaped the social geography, preventing Yazidis from returning to Sinjar ten years after the genocide. The area was liberated from ISIS in 2016, but the lack of security prevents Yazidis from reintegrating into Iraq. The region’s proximity to conflicts has attracted armed groups seeking strategic military position. The presence of many security actors and the lack of a centralised command and control hierarchy make the district unsafe. The Kurdish Workers Party (PKK) and the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) have established authority in Sinjar and created a military corridor to transport weapons and fighters to Syria. The Iraqi government’s attempts to contain the two groups has resulted in further violence. The lack of security and fear of revenge attacks have forced Yazidis to live in displacement camps for almost 10 years. The longer the government takes to stabilise the area, the greater the chances of new armed groups becoming entrenched. This would make it impossible for Yazidis to go back home. Even if Sinjar becomes safe, Yazidis are still living in displacement camps without documents, economic resources, or basic rights. Nearly a decade later, numerous villages display mass graves, dissuading people from returning due to the emotional distress it would evoke. Without material compensation for their losses, they can’t rebuild their homes. The government has shown no interest in rebuilding the region due to ongoing conflicts.

The anti-Yazidi rhetoric on social media constrains Yazidis in displacement camps. They fear attacks by neighbours and lack trust in regional institutions, hindering their return to Sinjar. Many Yazidis believe that Arab tribesmen and Sunni Turkmen who stayed in 2014 joined ISIS. The fear of another genocide is still strong. Despite Sinjar’s liberation from ISIS, Yazidis are reluctant to return due to a lack of laws protecting minorities in Iraq. The Iraqi government recognized ISIS actions against Yazidis and other minorities only in 2021, contributing to Yazidi’s feeling ofabandonment. Little has been done to bring justice to the thousands killed and protect Yazidis for their return.

Social Issues

The violence perpetrated by ISIS has affected generations of Yazidis, leading to depression and PTSD among survivors. Genocides have negative effects on individual survivors and communities, including witnessing extreme violence, torture, rape, sexual humiliation, and loss of family. Around 43% of escaped women and children show PTSD symptoms, while 40% have major depression (Ibrahim et al., 2018).

The psychological recovery of women who were kidnapped, raped, and enslaved is a serious problem. This is because displacement camps lack the medical and psychological help. Women also face rejection from their community after escaping. The Yazidi community is extremely religious and based on honour and purity. Thus, women who survived rape and sexual enslavement were ostracised. The trauma of rejection and the humiliation heightened their psychological trauma. Women who birthed children during their captivity faced increased rejection. The Yazidi Spiritual Council decreed that neither they nor their children could be accepted back into the community, as children born in captivity were considered sons of ISIS. Eventually, the Council reversed its decisions, accepting women back into the community, but not their children. This decision further endangered women’s situation in the area, as many were forced to leave their community to live with their children, or remained in captivity to safeguard their children’s lives. The trauma experienced by women during and after their captivity has been acknowledged by many international organisations. However, the lack of human and financial resources in displacement camps significantly hampers women’s access to medications and psychological support. The lack of medical support for psychological and social trauma affecting Yazidis hinders their return.

Bibliography

Brad C. Koenig, Human Security in Northern Iraq: The Yazidi Case Study, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, (2020)

Dr Zmkan Saleem, Dr Renad Mansour, Responding to instability in Iraq’s Sinjar district, Chatham House, (2024) https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/03/responding-instability-iraqs sinjar-district

Hawkar Ibrahim, Verena Ertl, Claudia Catani, Azad Ali Ismail and Frank Neuner, Trauma and perceived social rejection among Yazidi women and girls who survived enslavement and genocide, BMC Medicine, (2018) https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-018-1140-5

Iznt Noah, Sinjar: Challenges and Resilience Nine Years after Genocide, Fikra Forum, (2023) https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/sinjar-challenges-and-resilience-nine years-after-genocide

Majid Hassan Ali, The Forced Displacement of Ethnic and Religious Minorities in Disputed Areas in Iraq, Almuntaqa, (2022)

In this article Anna discussed post conflict regions. She is a student journalist with us on a placement organised by the Department of War Studies, King's College, London. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for your time. Don’t forget to share A4R 🎨 Media Hub. Every share helps.