Rwanda’s Road to Unity: Rebuilding a Post-Genocide Society

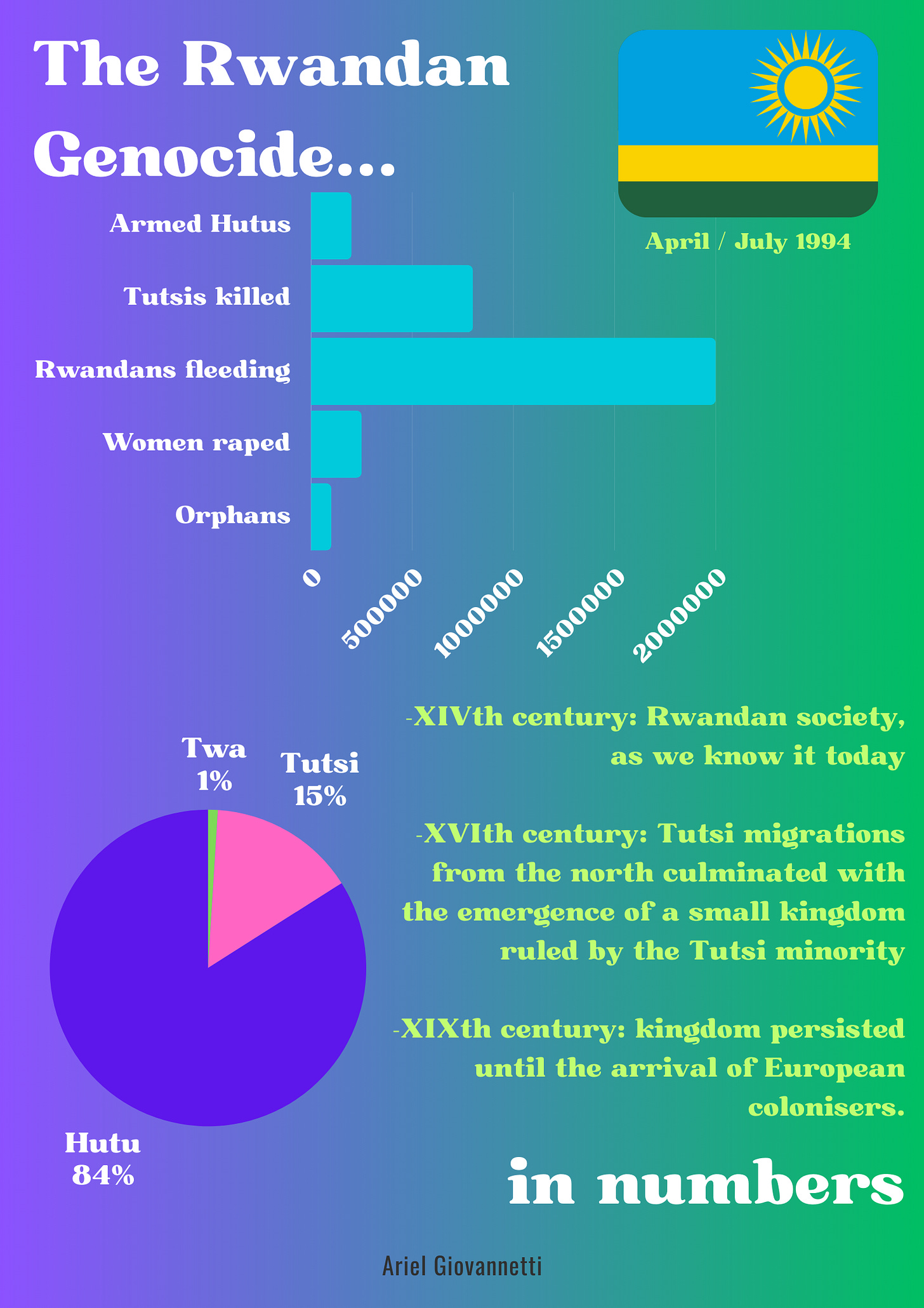

Between April and July 1994, Rwanda experienced the fastest genocide in history. This cataclysm, one of the most tragic events of the XXth century, led to the death of 800,000 people out of a population of 3.5 million, forever marking the history of both the country and the world. But if the victims constitute Rwanda’s scar, the survivors make it an open wound. Among the survivors, over 250,000 women were raped, 80,000 remained widows, and 100,000 children became orphans. In the midst of the event, many of the rapes resulted in pregnancies, and so thousands of children, who represented the most perverse outcome of the genocide, were born.

Contrary to the idea of an ancestral hatred or collective madness, the genocide is the result of deep-rooted racism, fueled by colonial and missionary legacies of an Europe obsessed with racial hierarchies. What distincts the Rwandan tragedy from many mass crimes is what Hélène Dumas refers to as a “genocide among neighbours” in her book Génocide au Village (“Genocide in the village”). In time, Hutus and Tutsis have always worked and lived close to each other, to the point where mixed families existed. The war generated an abnormal reality in which it was acceptable to sell your neighbour’s life to Hutu militias. Hence, the survivors still live today at close-distance to the perpetrators.

Having defined the judicial conditions of mass crimes soon after the Holocaust, one would think it would be the end of such atrocities, yet the Rwandan genocide was a bolt from the blue. Thus, this atrocity stands as one of the most harrowing events in modern history, fracturing communities, destroying trust, and undermining social cohesion. In a society where hate was once normalised, the path to restoring positive cultural narratives and a forward-moving society becomes a difficult one. This article’s aim will be to explain what issues Rwanda is still facing after 30 years, and what is being done to lead the country to unity.

The Blur Between the Past and the Present

Rwanda has had the same president for 24 years; Paul Kagame, former commander of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel armed force which invaded Rwanda in 1990 and conquered the entire country in July 1994, putting a stop to the genocide. But this “reconquest” hasn’t been led without any use of violence. In her book, In Praise of Blood: The Crimes of the Rwandan Patriotic Front, Canadian journalist Judi Rever offers a detailed account of the RPF’s crimes. The Black Agenda Report also stated that, in 2003, a whistleblower working at the ICTR sent Rever an official compendium of war crimes committed against civilians by Kagame’s army during the genocide. Nevertheless, neither the ICTR nor the Gacaca courts condemned the actions of the RPF, as the international community saw the group as the liberators of the country, and the U.S. saw Kagame as more suited for the role of president. Today, the RPF’s rule is widely recognised as authoritarian: according to Human Rights Watch, political opposition is repressed and censorship is heavily applied to all media.

In a world where many governments chose forgetfulness over remembrance, the Rwandan government deserves credit for its commitment. Yet even as a commendable effort, it has been proven that memorial days can be counter-effective.

Every 7th of April, date that marks the official start of the genocide, a national commemoration takes place, followed by an official week of mourning. Commemorative activities often involve visiting memorial sites, public testimonies, and sometimes even artistic re-enactments, which evoke vivid memories of loss. In their article published in 2016, The Tutsi Genocide Twenty Years Later, the French historians and Rwandan genocide experts Hélène Dumas and Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau tell us about something that took place on 7 April 2008: “In the silence, suddenly arise the screams of a woman; accompanied by convulsions and gestures of resistance to the caregivers who, forcibly, evacuate her from the building”.

The manifestations of these crises include emotional outbursts—such as crying and screaming—as well as more physical and severe symptoms like trembling and breathing difficulties. Survivors often also experience long-term psychological distress, including nightmares, flashbacks, and intense anxiety or panic. By talking to a friend who lives in Rwanda but prefers to stay anonymous, I learned that numerous ambulances are always parked in front of commemoration sites on every remembrance day, and that the Government makes sure to avoid any too closed off venues in order to facilitate the evacuation of people seized by breakdowns.

CC. Agence France Presse, 7 April 2014.

During a private conference held last spring at the French highschool of Rome, Lycée Chateaubriand, Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau talked about these crises, defining them as “hereditary syndromes”. In fact, he says that younger individuals, born decades after the events, can be subject to these outbursts. We can assert it isn’t a genetic condition, but Rouzeau’s observation might bring closer attention to the subject in the future, and reach a psychological explanation for it.

But the memorial path had to be accompanied by judicial measures in order to give justice to the family of the victims and to survivors.

On 8 November 1994, the UN Security Council established the International Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) "for the sole purpose of prosecuting persons responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law”. But the perpetrators were too numerous, and so the ICTR had to delegate some of the responsibility to makeshift local courts called Gacaca, which literally translates to “short grass”, where male elders used to meet to solve issues in their village.

Despite everything, the Gacaca courts faced significant backlash from multiple NGOs. One of the main criticisms regarded their members, who were elected among villagers and who often lacked the necessary qualifications and experience. Furthermore, many of these elected members were related to the very individuals being prosecuted, which resulted in disproportionately lenient sentences, undermining the credibility of the Gacaca system and raising serious concerns about its capacity to deliver fair and impartial justice.

CC. Gacaca court in Rwamagana district, a man is accused by a witness, 11 August 2006, Elisa Finocchiaro.

Rwanda Today: the Ongoing Efforts to Rebuild a Society

Under Belgian rule in 1926, compulsory identity cards were introduced, which included ethnic identity. This created a rigid system fixed from birth, which had never existed before. That’s right, there was no difference between Tutsi or Hutu: the only one being that the first looked over livestock, while the latter worked the soil.

A lot has also changed from a legal standpoint; declaring oneself Tutsi or Hutu is now a crime. There is no legal division among the people, they are all Rwandan.

And as we have already affirmed, efforts to promote empathy and reconciliation are essential for healing. But what is actually being done in order to move forward? We should start by explaining what “recovery capital” is, and we’ll do so by taking a look at a psychology article published by Frontiers in 2019, The Role of Recovery Capital in Growth from Trauma. Here, they explain it as a multidimensional concept that encompasses various resources individuals can use to overcome trauma. The researchers identified four key capital components:

1. Social Capital refers to the networks of support, trust, and shared norms that connect individuals within families, communities, and the broader society. Strong social ties foster a sense of belonging that is vital to nation-(re)building.

2. Cultural Capital encompasses the values, beliefs, knowledge, and skills individuals acquire through socialisation. It shapes people’s understanding of the world and influences their behaviours and coping mechanisms.

3. Physical Capital concerns tangible assets such as financial resources and property, as a response to the mass destruction of infrastructure that both Hutu and RPF militias perpetrated. In response to this, many of the penalties imposed by local courts, the “gacaca”, concern work of community interest such as building hospitals, schools and housing.

4. Human Capital includes “an individual’s knowledge, skills, health, and overall well-being”.

In the aftermath of the genocide, international organisations have been of service in fostering recovery and healing; first and foremost, the UN mission established by the Security Council Resolution 872 on 5 October 1993, before the horrible events took place.

Following this, two notable non-governmental organisations—ARCT-Ruhuka and International Alert—have made significant contributions; ARCT-Ruhuka, the national association of trauma counsellors, has focused on community-based interventions that emphasise mental health and psychosocial support, recognising that the healing process is deeply embedded within social structures and relationships, while International Alert has partnered with ARCT-Ruhuka since 2007, facilitating dialogue and reconciliation efforts that promote peace and understanding among the communities still grappling with the scars of the past. Through their comprehensive programs, which encompass everything from cognitive behavioural therapy to community dialogue sessions, ARCT-Ruhuka has trained local volunteers who provide support to those affected by the trauma of genocide, empowering Rwandans not only to address their own emotional scars but also to actively contribute to a collective healing process that strengthens community bonds.

CC. Alice Mukarurinda has forgiven Emanuel Ndayisaba, right, who tried to kill her during the genocide, Jack Picone, 7 April 2024.

In Rwanda, implemented initiatives promote healing, including truth and reconciliation commissions and community support programs. These efforts aim to create spaces for victims and perpetrators to share their experiences, seek forgiveness, and foster dialogue. But in all fairness, we could say that despite the strides made in promoting reconciliation, significant challenges remain. The demand for mental health services far exceeds available resources, and stigma surrounding mental health still prevents individuals from seeking help. By investing in social, cultural, physical, and human capital, the nation can foster a future where the wounds of the past are acknowledged and transformed into a catalyst for peace and growth. However, it is essential to recognize that healing from genocide is a long-term process that requires ongoing commitment, resources, and support from both the government, the international community, and the community itself.

A genocide, said Rory Stewart at an official visit in 2014, is too heavy to be forgotten and too repugnant to be integrated into the normal narrative of memory. Yet, life goes on; it must go on. Thirty years have passed since the genocide; the children born from and amidst violence have become adults: men and women who are the new protagonists of a new Rwanda.

In this episode Ariel discusses Rwanda post genocide rebuilding expereince. She is a student journalist with us on a placement organised with Department of War Studies, King’s College, London. This article was edited using Lex.page.

Thank you for reading an A4R 🎨 Post. Don’t forget to visit our gift shop here. Every purchase scales our impact and pays our bills.